|

|

|

How to Think Like a Computer Scientist |  |

Chapter 3

Functions

3.1 Function calls

You have already seen one example of a function call:

>>> type("32")

<type 'str'>

The name of the function is type, and it displays the type of a value or variable. The value or variable, which is called the argument of the function, has to be enclosed in parentheses. It is common to say that a function "takes" an argument and "returns" a result. The result is called the return value.

Instead of printing the return value, we could assign it to a variable:

>>> betty = type("32")

>>> print betty

<type 'str'>

As another example, the id function takes a value or a variable and returns an integer that acts as a unique identifier for the value:

>>> id(3)

134882108

>>> betty = 3

>>> id(betty)

134882108

Every value has an id, which is a unique number related to where it is stored in the memory of the computer. The id of a variable is the id of the value to which it refers.

3.2 Type conversion

Python provides a collection of built-in functions that convert values from one type to another. The int function takes any value and converts it to an integer, if possible, or complains otherwise:

>>> int("32")

32

>>> int("Hello")

ValueError: invalid literal for int(): Hello

int can also convert floating-point values to integers, but remember that it truncates the fractional part:

>>> int(3.99999)

3

>>> int(-2.3)

-2

The float function converts integers and strings to floating-point numbers:

>>> float(32)

32.0

>>> float("3.14159")

3.14159

Finally, the str function converts to type string:

>>> str(32)

'32'

>>> str(3.14149)

'3.14149'

It may seem odd that Python distinguishes the integer value 1 from the floating-point value 1.0. They may represent the same number, but they belong to different types. The reason is that they are represented differently inside the computer.

3.3 Type coercion

Now that we can convert between types, we have another way to deal with integer division. Returning to the example from the previous chapter, suppose we want to calculate the fraction of an hour that has elapsed. The most obvious expression, minute / 60, does integer arithmetic, so the result is always 0, even at 59 minutes past the hour.

One solution is to convert minute to floating-point and do floating-point division:

>>> minute = 59

>>> float(minute) / 60

0.983333333333

Alternatively, we can take advantage of the rules for automatic type conversion, which is called type coercion. For the mathematical operators, if either operand is a float, the other is automatically converted to a float:

>>> minute = 59

>>> minute / 60.0

0.983333333333

By making the denominator a float, we force Python to do floating-point division.

3.4 Math functions

In mathematics, you have probably seen functions like sin and log, and you have learned to evaluate expressions like sin(pi/2) and log(1/x). First, you evaluate the expression in parentheses (the argument). For example, pi/2 is approximately 1.571, and 1/x is 0.1 (if x happens to be 10.0).

Then, you evaluate the function itself, either by looking it up in a table or by performing various computations. The sin of 1.571 is 1, and the log of 0.1 is -1 (assuming that log indicates the logarithm base 10).

This process can be applied repeatedly to evaluate more complicated expressions like log(1/sin(pi/2)). First, you evaluate the argument of the innermost function, then evaluate the function, and so on.

Python has a math module that provides most of the familiar mathematical functions. A module is a file that contains a collection of related functions grouped together.

Before we can use the functions from a module, we have to import them:

>>> import math

To call one of the functions, we have to specify the name of the module and the name of the function, separated by a dot, also known as a period. This format is called dot notation.

>>> decibel = math.log10 (17.0)

>>> angle = 1.5

>>> height = math.sin(angle)

The first statement sets decibel to the logarithm of 17, base 10. There is also a function called log that takes logarithm base e.

The third statement finds the sine of the value of the variable angle. sin and the other trigonometric functions (cos, tan, etc.) take arguments in radians. To convert from degrees to radians, divide by 360 and multiply by 2*pi. For example, to find the sine of 45 degrees, first calculate the angle in radians and then take the sine:

>>> degrees = 45

>>> angle = degrees * 2 * math.pi / 360.0

>>> math.sin(angle)

0.707106781187

The constant pi is also part of the math module. If you know your geometry, you can check the previous result by comparing it to the square root of two divided by two:

>>> math.sqrt(2) / 2.0

0.707106781187

3.5 Composition

Just as with mathematical functions, Python functions can be composed, meaning that you use one expression as part of another. For example, you can use any expression as an argument to a function:

>>> x = math.cos(angle + math.pi/2)

This statement takes the value of pi, divides it by 2, and adds the result to the value of angle. The sum is then passed as an argument to the cos function.

You can also take the result of one function and pass it as an argument to another:

>>> x = math.exp(math.log(10.0))

This statement finds the log base e of 10 and then raises e to that power. The result gets assigned to x.

3.6 Adding new functions

So far, we have only been using the functions that come with Python, but it is also possible to add new functions. Creating new functions to solve your particular problems is one of the most useful things about a general-purpose programming language.

In the context of programming, a function is a named sequence of statements that performs a desired operation. This operation is specified in a function definition. The functions we have been using so far have been defined for us, and these definitions have been hidden. This is a good thing, because it allows us to use the functions without worrying about the details of their definitions.

The syntax for a function definition is:

def NAME( LIST OF PARAMETERS ):

STATEMENTS

You can make up any names you want for the functions you create, except that you can't use a name that is a Python keyword. The list of parameters specifies what information, if any, you have to provide in order to use the new function.

There can be any number of statements inside the function, but they have to be indented from the left margin. In the examples in this book, we will use an indentation of two spaces.

The first couple of functions we are going to write have no parameters, so the syntax looks like this:

def newLine():

print

This function is named newLine. The empty parentheses indicate that it has no parameters. It contains only a single statement, which outputs a newline character. (That's what happens when you use a print command without any arguments.)

The syntax for calling the new function is the same as the syntax for built-in functions:

print "First Line."

newLine()

print "Second Line."

The output of this program is:

First line.

Second line.

Notice the extra space between the two lines. What if we wanted more space between the lines? We could call the same function repeatedly:

print "First Line."

newLine()

newLine()

newLine()

print "Second Line."

Or we could write a new function named threeLines that prints three new lines:

def threeLines():

newLine()

newLine()

newLine()

print "First Line."

threeLines()

print "Second Line."

This function contains three statements, all of which are indented by two spaces. Since the next statement is not indented, Python knows that it is not part of the function.

You should notice a few things about this program:

- You can call the same procedure repeatedly. In fact, it is quite common and useful to do so.

- You can have one function call another function; in this case threeLines calls newLine.

So far, it may not be clear why it is worth the trouble to create all of these new functions. Actually, there are a lot of reasons, but this example demonstrates two:

- Creating a new function gives you an opportunity to name a group of statements. Functions can simplify a program by hiding a complex computation behind a single command and by using English words in place of arcane code.

- Creating a new function can make a program smaller by eliminating repetitive code. For example, a short way to print nine consecutive new lines is to call threeLines three times.

As an exercise, write a function called nineLines that uses threeLines to print nine blank lines. How would you print twenty-seven new lines?

3.7 Definitions and use

Pulling together the code fragments from Section 3.6, the whole program looks like this:

def newLine():

print

def threeLines():

newLine()

newLine()

newLine()

print "First Line."

threeLines()

print "Second Line."

This program contains two function definitions: newLine and threeLines. Function definitions get executed just like other statements, but the effect is to create the new function. The statements inside the function do not get executed until the function is called, and the function definition generates no output.

As you might expect, you have to create a function before you can execute it. In other words, the function definition has to be executed before the first time it is called.

As an exercise, move the last three lines of this program to the top, so the function calls appear before the definitions. Run the program and see what error message you get.

As another exercise, start with the working version of the program and move the definition of newLine after the definition of threeLines. What happens when you run this program?

3.8 Flow of execution

In order to ensure that a function is defined before its first use, you have to know the order in which statements are executed, which is called the flow of execution.

Execution always begins at the first statement of the program. Statements are executed one at a time, in order from top to bottom.

Function definitions do not alter the flow of execution of the program, but remember that statements inside the function are not executed until the function is called. Although it is not common, you can define one function inside another. In this case, the inner definition isn't executed until the outer function is called.

Function calls are like a detour in the flow of execution. Instead of going to the next statement, the flow jumps to the first line of the called function, executes all the statements there, and then comes back to pick up where it left off.

That sounds simple enough, until you remember that one function can call another. While in the middle of one function, the program might have to execute the statements in another function. But while executing that new function, the program might have to execute yet another function!

Fortunately, Python is adept at keeping track of where it is, so each time a function completes, the program picks up where it left off in the function that called it. When it gets to the end of the program, it terminates.

What's the moral of this sordid tale? When you read a program, don't read from top to bottom. Instead, follow the flow of execution.

3.9 Parameters and arguments

Some of the built-in functions you have used require arguments, the values that control how the function does its job. For example, if you want to find the sine of a number, you have to indicate what the number is. Thus, sin takes a numeric value as an argument.

Some functions take more than one argument. For example, pow takes two arguments, the base and the exponent. Inside the function, the values that are passed get assigned to variables called parameters.

Here is an example of a user-defined function that has a parameter:

def printTwice(bruce):

print bruce, bruce

This function takes a single argument and assigns it to a parameter named bruce. The value of the parameter (at this point we have no idea what it will be) is printed twice, followed by a newline. The name bruce was chosen to suggest that the name you give a parameter is up to you, but in general, you want to choose something more illustrative than bruce.

The function printTwice works for any type that can be printed:

>>> printTwice('Spam')

Spam Spam

>>> printTwice(5)

5 5

>>> printTwice(3.14159)

3.14159 3.14159

In the first function call, the argument is a string. In the second, it's an integer. In the third, it's a float.

The same rules of composition that apply to built-in functions also apply to user-defined functions, so we can use any kind of expression as an argument for printTwice:

>>> printTwice('Spam'*4)

SpamSpamSpamSpam SpamSpamSpamSpam

>>> printTwice(math.cos(math.pi))

-1.0 -1.0

As usual, the expression is evaluated before the function is run, so printTwice prints SpamSpamSpamSpam SpamSpamSpamSpam instead of 'Spam'*4 'Spam'*4.

As an exercise, write a call to printTwice that does print 'Spam'*4 'Spam'*4. Hint: strings can be enclosed in either single or double quotes, and the type of quote not used to enclose the string can be used inside it as part of the string.

We can also use a variable as an argument:

>>> michael = 'Eric, the half a bee.'

>>> printTwice(michael)

Eric, the half a bee. Eric, the half a bee.

Notice something very important here. The name of the variable we pass as an argument (michael) has nothing to do with the name of the parameter (bruce). It doesn't matter what the value was called back home (in the caller); here in printTwice, we call everybody bruce.

3.10 Variables and parameters are local

When you create a local variable inside a function, it only exists inside the function, and you cannot use it outside. For example:

def catTwice(part1, part2):

cat = part1 + part2

printTwice(cat)

This function takes two arguments, concatenates them, and then prints the result twice. We can call the function with two strings:

>>> chant1 = "Pie Jesu domine, "

>>> chant2 = "Dona eis requiem."

>>> catTwice(chant1, chant2)

Pie Jesu domine, Dona eis requiem. Pie Jesu domine, Dona eis requiem.

When catTwice terminates, the variable cat is destroyed. If we try to print it, we get an error:

>>> print cat

NameError: cat

Parameters are also local. For example, outside the function printTwice, there is no such thing as bruce. If you try to use it, Python will complain.

3.11 Stack diagrams

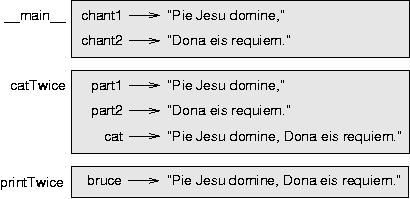

To keep track of which variables can be used where, it is sometimes useful to draw a stack diagram. Like state diagrams, stack diagrams show the value of each variable, but they also show the function to which each variable belongs.

Each function is represented by a frame. A frame is a box with the name of a function beside it and the parameters and variables of the function inside it. The stack diagram for the previous example looks like this:

The order of the stack shows the flow of execution. printTwice was called by catTwice, and catTwice was called by __main__, which is a special name for the topmost function. When you create a variable outside of any function, it belongs to __main__.

Each parameter refers to the same value as its corresponding argument. So, part1 has the same value as chant1, part2 has the same value as chant2, and bruce has the same value as cat.

If an error occurs during a function call, Python prints the name of the function, and the name of the function that called it, and the name of the function that called that, all the way back to __main__.

For example, if we try to access cat from within printTwice, we get a NameError:

Traceback (innermost last):

File "test.py", line 13, in __main__

catTwice(chant1, chant2)

File "test.py", line 5, in catTwice

printTwice(cat)

File "test.py", line 9, in printTwice

print cat

NameError: cat

This list of functions is called a traceback. It tells you what program file the error occurred in, and what line, and what functions were executing at the time. It also shows the line of code that caused the error.

Notice the similarity between the traceback and the stack diagram. It's not a coincidence.

3.12 Functions with results

You might have noticed by now that some of the functions we are using, such as the math functions, yield results. Other functions, like newLine, perform an action but don't return a value. That raises some questions:

- What happens if you call a function and you don't do anything with the result (i.e., you don't assign it to a variable or use it as part of a larger expression)?

- What happens if you use a function without a result as part of an expression, such as newLine() + 7?

- Can you write functions that yield results, or are you stuck with simple function like newLine and printTwice?

The answer to the last question is that you can write functions that yield results, and we'll do it in Chapter 5.

As an exercise, answer the other two questions by trying them out. When you have a question about what is legal or illegal in Python, a good way to find out is to ask the interpreter.

3.13 Glossary

- function call

- A statement that executes a function. It consists of the name of the function followed by a list of arguments enclosed in parentheses.

- argument

- A value provided to a function when the function is called. This value is assigned to the corresponding parameter in the function.

- return value

- The result of a function. If a function call is used as an expression, the return value is the value of the expression.

- type conversion

- An explicit statement that takes a value of one type and computes a corresponding value of another type.

- type coercion

- A type conversion that happens automatically according to Python's coercion rules.

- module

- A file that contains a collection of related functions and classes.

- dot notation

- The syntax for calling a function in another module, specifying the module name followed by a dot (period) and the function name.

- function

- A named sequence of statements that performs some useful operation. Functions may or may not take arguments and may or may not produce a result.

- function definition

- A statement that creates a new function, specifying its name, parameters, and the statements it executes.

- flow of execution

- The order in which statements are executed during a program run.

- parameter

- A name used inside a function to refer to the value passed as an argument.

- local variable

- A variable defined inside a function. A local variable can only be used inside its function.

- stack diagram

- A graphical representation of a stack of functions, their variables, and the values to which they refer.

- frame

- A box in a stack diagram that represents a function call. It contains the local variables and parameters of the function.

- traceback

- A list of the functions that are executing, printed when a runtime error occurs.

Warning: the HTML version of this document is generated from Latex and may contain translation errors. In particular, some mathematical expressions are not translated correctly.

|

|

|

How to Think Like a Computer Scientist |  |