In this chapter you'll learn how to open your community to users connecting from small mobile devices.

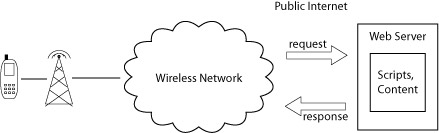

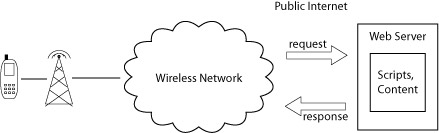

Figure 9.1: Content to mobile devices goes from an HTTP server on the public Internet via TCP/IP and is sometimes translated into proprietary formats and protocols within a phone company's wireless network before reaching the handset.

As illustrated above, the cell phone connects to your server through the service provider's wireless network. Depending on the phone and network, the "Wireless Network" cloud may contain standard Internet Protocol (IP) routing, a standard HTTP proxy, or a WAP gateway. In the last case, the gateway and phone communicate using a special set of protocols that, among other things, compresses data before transmission over the wireless network. The net effect is that the phone's browser (sometimes called a microbrowser) looks to a public HTTP server like a standard Web browser issuing HTTP GETs and POSTs.

The mobile industry is consuming markup languages at a rapid rate.

The progression has taken us from the Handheld Device Markup

Language (HDML; 1997) to the Wireless Markup Language (WML; 1998) to

the current recommendation, XHTML Mobile Profile (XHTML-MP; 2001).

We can take heart from the fact that XHTML-MP is derived from XHTML,

the World Wide Web Consortion recommendation for standard browsers.

Gone are the bad old days when a developer had to learn a new markup

language, and servers had to be configured to send new

Content-Type headers, in order to deliver mobile content.

We expect that XHTML-MP will thereby enjoy wider adoption and

greater stability.

|

Content is delivered in "XHTML Mobile Profile", a strict subset of XHTML, which is an XML-conformant version of HTML. Here's a shell session resulting in the return of an XHTML-MP document short enough to print in its entirety:

The text in bold (above) is what the programmer types, simulating a microbrowser request. The exchange looks a lot like what we'd see for a regular HTML browser. The main differences are the inclusion of the XML declaration and document-type definition in the first two lines of the document, and the use of the namespace attribute,

XHTML-MP Example Document % telnet philip.greenspun.com 80 Trying 216.127.244.134... Connected to philip.greenspun.com. Escape character is '^]'. GET /seia/mobile/ex1.html HTTP/1.0 HTTP/1.0 200 OK MIME-Version: 1.0 Content-Type: text/html <?xml version="1.0" encoding="UTF-8"?> <!DOCTYPE html PUBLIC "-//WAPFORUM//DTD XHTML Mobile 1.0//EN" "http://www.wapforum.org/DTD/xhtml-mobile10.dtd"> <html xmlns="http://www.w3.org/1999/xhtml" xml:lang="en"> <head> <title> XHTML-MP Example </title> </head> <body> <p>We're not in the 1970s anymore.</p> </body> </html> Connection closed by foreign host.

xmlns, in the opening html tag.

A server wishing to distinguish between desktop and mobile users could

search the contents of the HTTP Accept header for the

string application/xhtml+xml;

profile="http://www.wapforum.org/xhtml", which is supposedly

required by the XHTML Mobile Profile specification (http://www.openmobilealliance.org/tech/affiliates/wap/wap-277-xhtmlmp-20011029-a.pdf).

By contrast, a desktop browser, if it lists XHTML among the formats

that it accepts, will generally not refer to the mobile profile.

Here's what Microsoft Internet Explorer 6.0 supplies as an Accept

header:

image/gif, image/x-xbitmap, image/jpeg, image/pjpeg, application/vnd.ms-excel, application/vnd.ms-powerpoint, application/msword, application/x-shockwave-flash, */*

text/xml,application/xml,application/xhtml+xml,text/html;q=0.9,text/plain;q=0.8,video/x-mng,image/png,image/jpeg,image/gif;q=0.2,*/*;q=0.1

Note that Mozilla is making full use of the original conception of the

Web in which the server and the client would negotiate to provide the

user with the best possible file in response to a request for an

abstract URL. The order of the MIME types in the Accept header is

irrelevant. The browser indicates its preference with quality

values, for example in the value text/html;q=0.9,

Mozilla is indicating that plain vanilla HTML is less preferred than

the three preceding XML types, which default to a quality of 1.0. To

learn more about this system, see the section on "Quality Values" in

the HTTP 1.1 specification, at http://www.w3.org/Protocols/rfc2616/rfc2616.html

A second method for distinguishing between desktop and microbrowsers

is examining the User-Agent HTTP header. Consider the

following two shell sessions, in which the user-typed input is

highlighted in bold:

| No Extra Headers | Claiming to be a Palm |

|---|---|

% telnet www.google.com 80 Trying 216.239.57.99... Connected to www.google.com. Escape character is '^]'. GET / HTTP/1.1 HTTP/1.1 200 OK Date: Tue, 22 Apr 2003 01:20:53 GMT Cache-control: private Content-Type: text/html Server: GWS/2.0 Content-length: 2691 <html><head> <meta http-equiv="content-type" content="text/html; charset=ISO-8859-1"> <title>Google</title><style>...</style>... </head><body>...</body></html> Connection closed by foreign host. |

% telnet www.google.com 80 Trying 216.239.57.99... Connected to www.google.com. Escape character is '^]'. GET / HTTP/1.1 User-Agent: UPG1 UP/4.0 (compatible; Blazer 1.0) HTTP/1.1 302 Found Date: Tue, 22 Apr 2003 01:37:18 GMT Location: http://www.google.com/palm Content-Type: text/html Server: GWS/2.0 Content-length: 156 <HTML><HEAD><TITLE>302 Moved</TITLE></HEAD> <BODY> <H1>302 Moved</H1> The document has moved <A HREF="http://www.google.com/palm">here</A>. </BODY></HTML> Connection closed by foreign host. |

Though neither request indicates a preferred media type, Google's

server recognizes the "Blazer" browser that ships with Handspring

palm-top devices and redirects the browser, via the response lines

HTTP/1.1 302 Found and Location:

http://www.google.com/palm. Sadly, there is no centrally

maintained registry of user agents and therefore success with this

method is largely a matter of programmer diligence.

<?xml ...> declaration and running through

the closing </html> tag, into a file called

ex1.html on your Web server and load the example into

different kinds of browsers. We recommend that you place this file in

a /mbl/ subdirectory underneath your Web server's page root.

Step 2 — desktop browser. Now load the page into your favorite desktop browser program. Marvel at the cross-browser compatibility of your document. Compare your subjective experience of the content in the two cases, then answer the following question: In a world where desktop browsers and mobile browsers can parse the same markup syntax, do we need to distinguish between the two, or can we serve the same document to every type of user?

A numbered series of choices is presented in a list, with each choice

hyperlinked to the appropriate target. We take advantage of the

anchor tag's accesskey attribute to improve usability by

letting the user link to any of the choices with a single keypress.

For authentication via cookies, you need to go back to the form built

for Exercise 4 and back it up with a script that generates a

Set-Cookie header with an authentication token. We

recommend that you make this cookie persistent since typing a full email

address is pretty painful on a numeric keypad. Note that on an

organization's intranet site you can autocomplete the "@foobar.com" or

"@yow.org" portion of the email address for most users.

Background: The Paper Chase (1973, dir. James Bridges).

This is a good opportunity to be creative. Browsing from a phone can be slow, expensive, and painful. Every line of information has to be critically important to the user. To get you started, here are a few ideas:

Write down the client's answers to the following questions:

Depending on the user's wireless service provider, there may be

opportunities to push text or multimedia messages out to your user as

interesting events unfold within your community. Many mobile phones,

for example, can receive short text messages through the email system.

The phone's "email address" is formed by appending a provider-specific

domain to the phone's voice number. So if John's Verizon Wireless

phone number is 617-555-1212, we can alert him by sending email to

6175551212@vtext.com.

Western mobile Internet systems typically involved a dialup and sign-on delay of as long as two minutes for the first page; with the always-on i-mode system, the user gets consistent performance and relatively quick results for initial requests. Early Western mobile systems charged per minute, which was painful for users who typed text slowly on numeric keypads and received pages at 9800 baud. Always-on systems such as i-mode tend to charge a per-byte or flat per-month rate for access, which greatly reduces the possibility of a huge end-of-month bill.

In most mobile Internet systems, the phone company decides what sites are going to be interesting to users and places them on a set of default bookmarks. The phone company often charges the site publisher to be promoted to its customers. The result? Every early system in the U.S. made it easy to connect to amazon.com and shop for books, which turned out not to be a popular activity. DoCoMo, the Japanese company that runs the i-mode service, took a different approach. DoCoMo decided that they weren't creative enough to figure out what consumers would want out of the mobile Internet. They therefore came up with a system in which content providers are more or less equally available. Content providers can earn revenue via banner advertisements or by charging for premium content. When a provider wants to charge, DoCoMo handles the payment, taking a 5-9 percent commission.

The combination of always-on and non-starvation for content providers created an explosion of creativity on the part of publishers. The most popular services seem to be those that connect people with other people, rather than business-to-consumer amazon.com-style e-commerce.

Is there hope that the mobile Internet will eventually become as popular as i-mode is in Japan? The first ray of hope was provided by General Packet Radio Service (GPRS). GPRS takes advantage of lulls in voice traffic within a cell to deliver a theoretically maximum of 160Kbits/second via unused frequencies at any particular moment. GPRS requires new handsets that are equipped to listen simultaneously on both the dedicated circuit-switched connection in use for a voice call and also monitor GPRS frequencies for incoming packets. In practice, GPRS may provide only three or four times faster throughput than existing WAP systems. More important is the fact that GPRS can, in theory, deliver an "always-on" experience similar to that of i-mode or a hardwired desktop computer.

As noted above, with GPRS the wireless Internet will become a place that supports simultaneous voice and text interaction. For example, the following scenario can be realized:

There is no evidence that the phone companies outside Japan will wise up to the power of revenue sharing. However, with the introduction of GPRS the wireless Internet will become something better than a novelty. For more on the subject of GPRS see Peter Rysavy's "Emerging Technology: Clear Signals for General Packet Radio Service" in Network Magazine, December 2000 (http://www.rysavy.com/Articles/GPRS2/gprs2.html).

The team should plan to spend one to two hours together designing the mobile interface, but may divide the work of prototyping and refining the mobile interface. A reasonable scope is eight to twelve programmer-hours.

The time required for client signoff will vary depending on the client's level of interest and familiarity with the mobile Web. Plan to spend at least thirty minutes on the signoff.