This chapter describes the fundamental concepts that

underly all Motif dialogs. It provides a foundation for the more

advanced material in the following chapters. In the course of the

introduction, the chapter also provides information about Motif's

predefined MessageDialog classes.

In Chapter 4, The Main Window, we discussed

the top-level windows that are managed by the window manager and that

provide the overall framework for an application. Most applications are

too complex to do everything in one main top-level window. Situations

arise that call for secondary windows, or transient windows,

that serve specific purposes. These windows are commonly referred to as

dialog boxes, or more simply as dialogs.

Dialog boxes play an integral role in a GUI-based

interface such as Motif. The examples in this book use dialogs in many

ways, so just about every chapter can be used to learn more about

dialogs. We've already explored some of the basic concepts in

Chapter 2, The Motif Programming Model, and Chapter 3,

Overview of the Motif Toolkit. However, the use of dialogs in Motif

is quite complex, so we need more detail to proceed further.

The Motif Style Guide makes a set of generic

recommendations about how all dialogs should look. The Style Guide

also specifies precisely how certain dialogs should look, how they

should respond to user events, and under what circumstances the dialogs

should be used. We refer to these dialogs as predefined Motif dialogs,

since the Motif toolkit implements each of them for you. These dialogs

are completely self-sufficient, opaque objects that require very little

interaction from your application. In most situations, you can create

the necessary dialog using a single convenience routine and you're

done. If you need more functionality than what is provided by a

predefined Motif dialog, you may have to create your own customized

dialog. In this case, building and handling the dialog requires a

completely different approach.

There are three chapters on basic dialog usage in

this book--two on the predefined Motif dialogs and one on customized

dialogs. There is also an additional chapter later in the book that

deals with more advanced dialog topics. This first chapter discusses

the most common class of Motif dialogs, called MessageDialogs. These

are the simplest kinds of dialogs; they typically display a short

message and use a small set of standard responses, such as OK,

Yes, or No. These dialogs are transient, in that they are

intended to be used immediately and then dismissed. MessageDialogs

define resources and attributes that are shared by most of the other

dialogs in the Motif toolkit, so they provide a foundation for us to

build upon in the later dialog chapters. Although Motif dialogs are

meant to be opaque objects, we will examine their implementation and

behavior in order to understand how they really work. This information

can help you understand not only what is happening in your application,

but also how to create customized dialogs.

Chapter 6, Selection Dialogs, describes

another set of predefined Motif dialogs, called SelectionDialogs. Since

these dialogs are the next step in the evolution of dialogs, most of

the material in this chapter is applicable there as well.

SelectionDialogs typically provide the user with a list of choices.

These dialogs can remain displayed on the screen so that they can be

used repeatedly. Chapter 7, Custom Dialogs, addresses the issues

of creating customized dialogs, and Chapter 21, Advanced Dialog

Programming, discusses some advanced topics in X and Motif

programming using dialogs as a backdrop.

For most applications, it is impossible to develop

an interface that provides the full functionality of the application in

a single main window. As a result, the interface is typically broken up

into discrete functional modules, where the interface for each module

is provided in a separate dialog box.

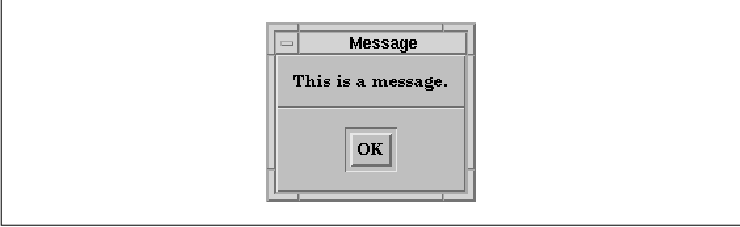

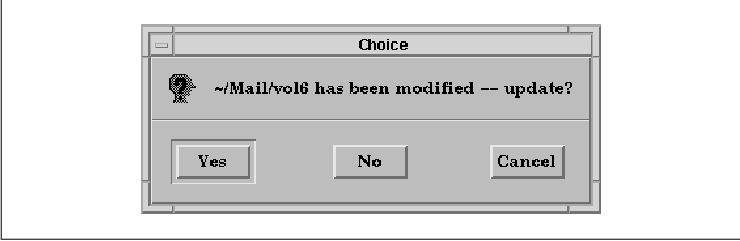

As an example, consider an electronic mail

application. The broad range of different functions includes searching

for messages according to patterns, composing messages, editing an

address book, reporting error messages, and so on. Dialog boxes are

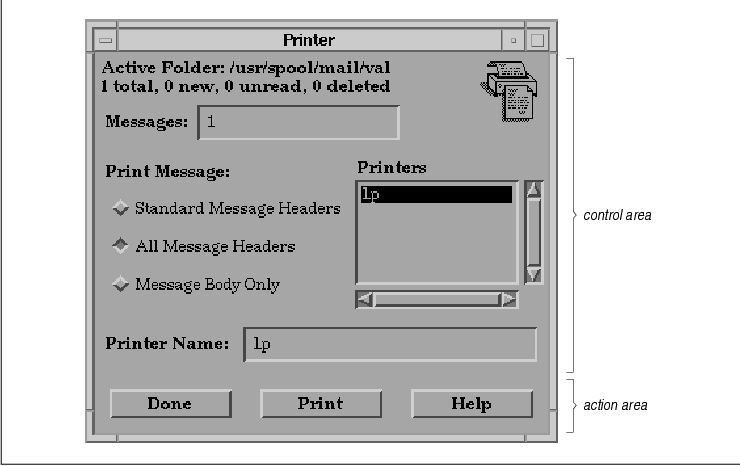

used to display simple messages, as shown in the figure. They are also

used to prompt the user to answer simple questions, as shown in the

figure. A dialog box can also present a more complicated interaction,

as shown in the figure.

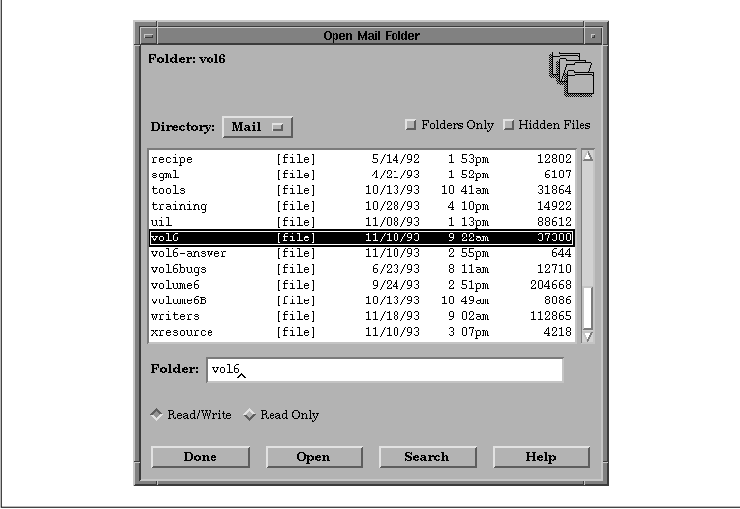

In the figure, many different widget classes are

used to provide an interface that allows the user to save e-mail

messages in different folders. The purpose of a dialog is to focus on

one particular task in an application. Since the scope of these tasks

is usually quite limited, an application usually provides them in

dialog boxes, rather than in its main window.

There is actually no such thing as a dialog widget

class in the Motif toolkit. A dialog is actually made up of a

DialogShell widget and a manager widget child that implements the

visible part of the dialog. The DialogShell interacts with the window

manager to provide the transient window behavior required of dialogs.

When we refer to a dialog widget, we are really talking about the

manager widget and all of its children collectively.

When you write a custom dialog, you simply create

and manage the children of the DialogShell in the same way that you

create and manage the children of a top-level application shell. The

predefined Motif dialogs follow the same approach, except that the

toolkit creates the manager widget and all of its children internally.

Most of the standard Motif dialogs are composed of a DialogShell and

either a MessageBox or SelectionBox widget. Each of these widget

classes creates and manages a number of internal widgets without

application intervention. See Chapter 3, Overview of the Motif

Toolkit, to review the various types of predefined Motif dialogs.

All of the predefined Motif dialogs are subclassed

from the BulletinBoard widget class. As such, a BulletinBoard can be

thought of as the generic dialog widget class, although it can

certainly be used as generic manager widget (see Chapter 8, Manager

Widgets). Indeed, a dialog widget is a manager widget, but it is

usually not treated as such by the application. The BulletinBoard

widget provides the keyboard traversal mechanisms that support gadgets,

as well as a number of dialog-specific resources.

It is important to note that for the predefined

Motif dialogs, each dialog is implemented as a single widget class,

even though there are smaller, primitive widgets under the hood. When

you create a MessageBox widget, you automatically get a set of Labels

and PushButtons that are laid out as described in the Motif Style

Guide. What is not created automatically is the DialogShell widget

that manages the MessageBox widget. You can either create the shell

yourself and place the MessageBox in it or use a Motif convenience

routine that creates both the shell and its dialog widget child.

The Motif toolkit uses the DialogShell widget class

as the parent for all of the predefined Motif dialogs. In this context,

a MessageBox widget combined with a DialogShell widget creates what the

Motif toolkit calls a MessageDialog. A careful look at terminology can

help you to distinguish between actual widget class and Motif compound

objects. The name of the actual widget class ends in Box,

while the name of the compound object made up of the widget and a

DialogShell ends in Dialog. For example, the convenience

routine XmCreateMessageBox() creates a MessageBox widget,

which you need to place inside of a DialogShell yourself.

Alternatively, XmCreateMessageDialog() creates a MessageDialog

composed of a MessageBox and a DialogShell.

Another point about terminology involves the

commonly-used term dialog box. When we say dialog box, we are referring

to a compound object composed of a DialogShell and a dialog widget, not

the dialog widget alone. This terminology can be confusing, since the

Motif toolkit also provides widget classes that end in box.

One subtlety in the use of MessageBox and

SelectionBox widgets is that certain types of behavior depend on

whether or not the widget is a direct child of a DialogShell. For

example, the Motif Style Guide says that clicking on the OK

button in the action area of a MessageDialog invokes the action of the

dialog and then dismisses the dialog. Furthermore, pressing the RETURN

key anywhere in the dialog is equivalent to clicking on the OK

button. However, none of this takes place when the MessageBox widget is

not a direct child of a DialogShell.

Perhaps the most important thing to remember is how

the Motif toolkit treats dialogs. Once a dialog widget is placed in a

DialogShell, the toolkit tends to treat the entire combination as a

single entity. In fact, as we move on, you'll find that the toolkit's

use of convenience routines, callback functions, and popup widget

techniques all hide the fact that the dialog is composed of these

discrete elements. While the Motif dialogs are really composed of many

primitive widgets, such as PushButtons and TextFields, the

single-entity approach implies that you never access the subwidgets

directly. If you want to change the label for a button, you set a

resource specific to the dialog class, rather than getting a handle to

the button widget and changing its resource. Similarly, you always

install callbacks on the dialog widget itself, instead of installing

them directly on buttons in the control or action areas.

This approach may be confusing for those already

familiar with Xt programming, but not yet familiar with the Motif

toolkit. Similarly, those who learn Xt programming through experiences

with the Motif toolkit might get a misconception of what Xt programming

is all about. We try to point out the inconsistencies between the two

approaches so that you will understand the boundaries between the Motif

toolkit and its Xt foundations.

As described in Chapter 3, Overview of the Motif

Toolkit, dialogs are typically broken down into two regions known

as the control and action areas. The control area is also referred to

as the work area. The control area contains the widgets that provide

the functionality of the dialog, such as Labels, ToggleButtons, and

List widgets. The action area contains PushButtons whose callback

routines actually perform the action of the dialog box. While most

dialogs follow this pattern, it is important to realize that these two

regions represent user-interface concepts and do not necessarily

reflect how Motif dialogs are implemented.

the figure shows these areas in a sample dialog box.

The Motif Style Guide describes in a general

fashion how the control and action areas for all dialogs should be laid

out. For predefined Motif dialogs, the control area is rigidly

specified. For customized dialogs, there is only a general set of

guidelines to follow. The guidelines for the action area specify a

number of common actions that can be used in both predefined Motif

dialogs and customized dialogs. These actions have standard meanings

that help ensure consistency between different Motif applications.

By default, the predefined Motif MessageDialogs

provide three action buttons, which are normally labeled OK,

Cancel, and Help, respectively. SelectionDialogs provide a

fourth button, normally labeled Apply, which is placed between

the OK and Cancel buttons. This button is created but not

managed, so it is not visible unless the application explicitly manages

it. The Style Guide specifies that the OK button applies

the action of the dialog and dismisses it, while the Apply

button applies the action but does not dismiss the dialog. The

Cancel button dismisses the dialog without performing any action

and the Help button provides any help that is available for the

dialog. When you are creating custom dialogs, or even when you are

using the predefined Motif dialogs, you may need to provide actions

other than the default ones. If so, you should change the labels on the

buttons so that the actions are obvious. You should try to use the

common actions defined by the Motif Style Guide if they are

appropriate, since these actions have standard meanings. We will

address this issue further as it comes up in discussion; it is not

usually a problem until you create your own customized dialogs, as

described in Chapter 7, Custom Dialogs.

Under most circumstances, creating a predefined

Motif dialog box is very simple. All Motif dialog types have

corresponding convenience routines that simplify the task of creating

and managing them. For example, a standard MessageDialog can be created

as shown in the following code fragment:

#include <Xm/MessageB.h>

extern Widget parent;

Widget dialog;

Arg arg[5];

XmString t;

int n = 0;

t = XmStringCreateLocalized ("Hello World");

XtSetArg (arg[n], XmNmessageString, t); n++;

dialog = XmCreateMessageDialog (parent, "message", arg, n);

XmStringFree (t);

The convenience routine does almost everything automatically. The only

thing that we have to do is specify the message that we want to

display.

As we mentioned earlier, there are two basic types

of predefined Motif dialog boxes: MessageDialogs and SelectionDialogs.

MessageDialogs present a simple message, to which a yes (OK) or

no (Cancel) response usually suffices. There are six types of

MessageDialogs: ErrorDialog, InformationDialog, QuestionDialog,

TemplateDialog, WarningDialog, and WorkingDialog. These types are not

actually separate widget classes, but rather instances of the generic

MessageDialog that are configured to display different graphic symbols.

All of the MessageDialogs are compound objects that are composed of a

MessageBox widget and a DialogShell. When using MessageDialogs, you

must include the file <Xm/MessageB.h>.

SelectionDialogs allow for more complicated

interactions. The user can select an item from a list or type an entry

into a TextField widget before acting on the dialog. There are

essentially four types of SelectionDialogs, although the situation is a

bit more complex than for MessageDialogs. The PromptDialog is a

specially configured SelectionDialog; both of these dialogs are

compound objects that are composed of a SelectionBox widget and a

DialogShell. The Command widget and the FileSelectionDialog are based

on separate widget classes. However, they are both subclassed from the

SelectionBox and share many of its features. When we use the general

term "selection dialogs," we are referring to these three widget

classes plus their associated dialog shells. To use a SelectionDialog,

you must include the file <Xm/SelectioB.h>. Yes, you read that

right. It does, in fact, read SelectioB.h. The reason for the

missing n is there is a fourteen-character filename limit on

UNIX System V machines. For FileSelectionDialogs, the appropriate

include file is <Xm/FileSB.h>, and for the Command widget it is

<Xm/Command.h>.

You can use any of the following convenience

routines to create a dialog box. They are listed according to the

header file in which they are declared:

<Xm/MessageB.h>:

XmCreateMessageBox() XmCreateMessageDialog() XmCreateErrorDialog() XmCreateInformationDialog() XmCreateQuestionDialog() XmCreateTemplateDialog() XmCreateWarningDialog() XmCreateWorkingDialog()<Xm/SelectioB.h>:

XmCreateSelectionBox() XmCreateSelectionDialog() XmCreatePromptDialog()<Xm/FileSB.h>:

XmCreateFileSelectionBox() XmCreateFileSelectionDialog()<Xm/Command.h>:

XmCreateCommand()Each of these routines creates a dialog widget. In addition, the routines that end in Dialog automatically create a DialogShell as the parent of the dialog widget. All of the convenience functions for creating dialogs use the standard Motif creation routine format. For example, XmCreateMessageDialog() takes the following form:

Widget

XmCreateMessageDialog(parent, name, arglist, argcount)

Widget parent;

String *name;

ArgList arglist;

Cardinal argcount;

In this case, we are creating a common MessageDialog, which is a

MessageBox with a DialogShell parent. The parent

parameter specifies the widget that acts as the owner or parent of the

DialogShell. Note that the parent must not be a gadget, since the

parent must have a window associated with it. The dialog widget itself

is a child of the DialogShell. You are returned a handle to the newly

created dialog widget, not the DialogShell parent. For the routines

that just create a dialog widget, the parent parameter

is simply a manager widget that contains the dialog.

The arglist and argcount

parameters for the convenience routines specify resources using the

old-style ArgList format, just like the rest of the Motif

convenience routines. A varargs-style interface is not available for

creating dialogs. However, you can use the varargs-style interface for

setting resources on a dialog after is has been created by using

XtVaSetValues().

There are a number of resources and callback

functions that apply to almost all of the Motif dialogs. These

resources deal with the action area buttons in the dialogs. Other

resources only apply to specific types of dialogs; they deal with the

different control area components such as Labels, TextFields, and List

widgets. The different resources are listed below, grouped according to

the type of dialogs that they affect:

General dialog resources:

XmNokLabelString XmNokCallback XmNcancelLabelString XmNcancelCallback XmNhelpLabelString XmNhelpCallbackMessageDialog resources:

XmNmessageString XmNsymbolPixmapSelectionDialog resources:

XmNapplyLabelString XmNapplyCallback XmNselectionLabelString XmNlistLabelStringFileSelectionDialog resources:

XmNfilterLabelString XmNdirListLabelString XmNfileListLabelStringCommand resources:

XmNpromptStringThe labels and callbacks of the various buttons in the action area are specified by resources based on the standard Motif dialog button names. For example, the XmNokLabelString resource is used to set the label for the OK button. XmNokCallback is used to specify the callback routine that the dialog should call when that button is activated. As discussed earlier, it may be appropriate to change the labels of these buttons, but the resource and callback names will always have names that correspond to their default labels.

The XmNmessageString resource specifies the

message that is displayed by the MessageDialog. The XmNsymbolPixmap

resource specifies the iconic symbol that is associated with each of

the MessageDialog types. This resource is rarely changed, so discussion

of it is deferred until Chapter 21, Advanced Dialog Programming.

The other resources apply to the different types of

selection dialogs. For example, XmNselectionLabelString sets

the label that is placed above the list area in SelectionDialog. These

resources are discussed in Chapter 6, Selection Dialogs.

All of these resources apply to the Labels and

PushButtons in the different dialogs. It is important to note that they

are different from the usual resources for Labels and PushButtons. For

example, the Label resource XmNlabelString would normally be

used to specify the label for both Label and PushButton widgets.

Dialogs use their own resources to maintain the abstraction of the

dialog widget as a discrete user-interface object.

Another important thing to remember about the

resources that refer to widget labels is that their values must be

specified as compound strings. Compound strings allow labels to be

rendered in arbitrary fonts and to span multiple lines. See Chapter 19,

Compound Strings, for more information.

The following code fragment demonstrates how to

specify dialog resources and callback routines:

Widget dialog;

XmString msg, yes, no;

extern void my_callback();

dialog = XmCreateQuestionDialog (parent, "dialog", NULL, 0);

yes = XmStringCreateLocalized ("Yes");

no = XmStringCreateLocalized ("No");

msg = XmStringCreateLocalized ("Do you want to quit?");

XtVaSetValues (dialog, XmNmessageString, msg, XmNokLabelString, yes, XmNcancelLabelString, no, NULL); XtAddCallback (dialog, XmNokCallback, my_callback, NULL); XtAddCallback (dialog, XmNcancelCallback, my_callback, NULL); XmStringFree (yes); XmStringFree (no); XmStringFree (msg);

None of the Motif toolkit convenience functions

manage the widgets that they create, so the application must call

XtManageChild() explicitly. It just so happens that managing a

dialog widget that is the immediate child of a DialogShell causes the

entire dialog to pop up. Similarly, unmanaging the same dialog widget

causes it and its DialogShell parent to pop down. This behavior is

consistent with the Motif toolkit's treatment of the dialog/shell

combination as a single object abstraction. The toolkit is treating its

own dialog widgets as opaque objects and trying to hide the fact that

there are DialogShells associated with them. The toolkit is also making

the assumption that when the programmer manages a dialog, she wants it

to pop up immediately.

This practice is somewhat presumptuous and it

conflicts directly with the specifications for the X Toolkit

Intrinsics. These specifications say that when the programmer wants to

display a popup shell on the screen, she should use XtPopup().

Similarly, when the dialog is to be dismissed, the programmer should

call XtPopdown(). The fact that XtManageChild()

happens to pop up the shell and XtUnmanageChild() causes it to

pop down is misleading to the new Motif programmer and confusing to the

experienced Xt programmer.

You should understand that this discussion of

managing dialogs does not apply to customized dialogs that you create

yourself. It only applies to the predefined Motif dialog widgets that

are created as immediate children of DialogShells. The Motif toolkit

uses this method because it has been around for a long time and it must

be supported for backwards compatibility with older versions.

Furthermore, using XtPopup() requires access to the

DialogShell parent of a dialog widget, which breaks the single-object

abstraction.

There are two ways to manage Motif dialogs. You can

follow the Motif toolkit conventions of using XtManageChild()

and XtUnmanageChild() to pop up and pop down dialog widgets or

you can use XtPopup() and XtPopdown() on the dialog's

parent to do the same job. Whatever you do, it is good practice to pick

one method and be consistent throughout an application. It is possible

to mix and match the methods, but there may be some undesirable side

effects, which we will address in the next few sections.

In an effort to make our applications easier to port

to other Xt-based toolkits, we follow the established convention of

using XtPopup(). This technique can coexist easily with

XtManageChild(), since popping up an already popped-up shell has no

effect. XtPopup() takes the following form:

void

XtPopup(shell, grab_kind)

Widget shell;

XtGrabKind grab_kind;

The shell parameter to the function must be a shell

widget; in this case it happens to be a DialogShell. If you created the

dialog using one of the Motif convenience routines, you can get a

handle to the DialogShell by calling XtParent() on the dialog

widget.

The grab_kind parameter can be one

of XtGrabNone, XtGrabNonexclusive, or

XtGrabExclusive. We almost always use XtGrabNone, since

the other values imply a server grab, which means that other

windows on the desktop are locked out. Grabbing the server results in

what is called modality; it implies that the user cannot

interact with anything but the dialog. While a grab may be desirable in

some cases, the Motif toolkit provides some predefined resources that

handle the grab for you automatically. The advantage of using this

alternate method is that it allows the client to communicate more

closely with the Motif Window Manager (mwm) and it provides for

different kinds of modality. These methods are discussed in Section

#smodaldlg. For detailed information on XtPopup() and the

different uses of grab_kind, see Volume Four, X

Toolkit Intrinsics Programming Manual.

If you call XtPopup() on a dialog widget

that has already been popped up using XtManageChild(), the

routine has no effect. As a result, if you attempt to specify

grab_kind as something other than XtGrabNone, it also

has no effect.

The counterpart to XtPopup() is

XtPopdown(). Any time you want to pop down a shell, you can use

this function, which has the following form:

void

XtPopdown(shell)

Widget shell;

Again, the shell parameter should be the XtParent()

of the dialog widget. If you use XtUnmanageChild() to pop down

a dialog, it is not necessary to call XtPopdown(), although we

advise it for correctness and good form. However, it is important to

note that if you use XtUnmanageChild() to pop down a dialog,

you must use XtManageChild() to redisplay it again. Don't

forget that the dialog widget itself is not a shell, so managing or

unmanaging it still takes place when you use the manage and unmanage

functions.

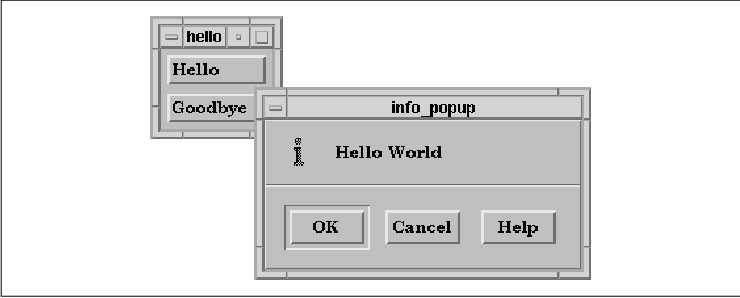

Let's take a closer look at how dialogs are really

used in an application. Examining the overall design and the mechanics

that are involved will help to clarify a number of issues about

managing and unmanaging dialogs and DialogShells. The program listed in

the source code displays an InformationDialog when the user presses a

PushButton in the application's main window. XtSetLanguageProc()

is only available in X11R5; there is no corresponding function in

X11R4. XmStringCreateLocalized() is only available in Motif

1.2; XmStringCreateSimple() is the corresponding function in

Motif 1.1.

/* hello_dialog.c -- your typical Hello World program using

* an InformationDialog.

*/

#include <Xm/RowColumn.h>

#include <Xm/MessageB.h>

#include <Xm/PushB.h>

main(argc, argv)

int argc;

char *argv[];

{

XtAppContext app;

Widget toplevel, rc, pb;

extern void popup(); /* callback for the pushbuttons -- pops up dialog */

extern void exit();

XtSetLanguageProc (NULL, NULL, NULL);

toplevel = XtVaAppInitialize (&app, "Demos", NULL, 0,

&argc, argv, NULL, NULL);

rc = XtVaCreateWidget ("rowcol",

xmRowColumnWidgetClass, toplevel, NULL);

pb = XtVaCreateManagedWidget ("Hello",

xmPushButtonWidgetClass, rc, NULL);

XtAddCallback (pb, XmNactivateCallback, popup, "Hello World");

pb = XtVaCreateManagedWidget ("Goodbye",

xmPushButtonWidgetClass, rc, NULL);

XtAddCallback (pb, XmNactivateCallback, exit, NULL);

XtManageChild (rc);

XtRealizeWidget (toplevel);

XtAppMainLoop (app);

}

/* callback for the PushButtons. Popup an InformationDialog displaying

* the text passed as the client data parameter.

*/

void

popup(button, client_data, call_data)

Widget button;

XtPointer client_data;

XtPointer call_data;

{

Widget dialog;

XmString xm_string;

extern void activate();

Arg args[5];

int n = 0;

char *text = (char *) client_data;

/* set the label for the dialog */

xm_string = XmStringCreateLocalized (text);

XtSetArg (args[n], XmNmessageString, xm_string); n++;

/* Create the InformationDialog as child of button */

dialog = XmCreateInformationDialog (button, "info", args, n);

/* no longer need the compound string, free it */

XmStringFree (xm_string);

/* add the callback routine */

XtAddCallback (dialog, XmNokCallback, activate, NULL);

/* manage the dialog */

XtManageChild (dialog);

XtPopup (XtParent (dialog), XtGrabNone);

}

/* callback routine for when the user presses the OK button.

* Yes, despite the fact that the OK button was pressed, the

* widget passed to this callback routine is the dialog!

*/

void

activate(dialog, client_data, call_data)

Widget dialog;

XtPointer client_data;

XtPointer call_data;

{

puts ("OK was pressed.");

}

The output of this program is shown in the figure.

Dialogs are often invoked from callback routines

attached to PushButtons or other interactive widgets. Once the dialog

is created and popped up, control of the program is returned to the

main event-handling loop (XtAppMainLoop()), where normal event

processing resumes. At this point, if the user interacts with the

dialog by selecting a control or activating one of the action buttons,

a callback routine for the dialog is invoked. In the source code we

happen to use an InformationDialog, but the type of dialog used is

irrelevant to the model.

When the PushButton in the main window is pressed,

popup() is called. A text string that is used as the message to

display in the InformationDialog is passed as client data. The dialog

uses a single callback routine, activate(), for the

XmNokCallback resource. This function is invoked when the user

presses the OK button. The callback simply prints a message to

standard output that the button has been pressed. Similar callback

routines could be installed for the Cancel and Help

buttons through the XmNcancelCallback and XmNhelpCallback

resources.

You might notice that activating either the OK

or the Cancel button in the previous example causes the dialog

to be automatically popped down. The Motif Style Guide says that

when any button in the action area of a predefined Motif dialog is

pressed, except for the Help button, the dialog should be

dismissed. The Motif toolkit takes this specification at face value and

enforces the behavior, which is consistent with the idea that Motif

dialogs are self-contained, self-sufficient objects. They manage

everything about themselves from their displays to their interactions

with the user. And when it's time to go away, they unmanage themselves.

Your application does not have to do anything to cause any of the

behavior to occur.

Unfortunately, this behavior does not take into

account error conditions or other exceptional events that may not

necessarily justify the dialog's dismissal. For example, if pressing

OK causes a file to be updated, but the operation fails, you may

not want the dialog to be dismissed. If the dialog is still displayed,

the user can try again without having to repeat the actions that led to

popping up the dialog.

The XmNautoUnmanage resource provides a way

around the situation. This resource controls whether the dialog box is

automatically unmanaged when the user selects an action area button

other than the Help button. If XmNautoUnmanage is

True, after the callback routine for the button is invoked, the

DialogShell is popped down and the dialog widget is unmanaged

automatically. However, if the resource is set to False, the

dialog is not automatically unmanaged. The value of this resource

defaults to True for MessageDialogs and SelectionDialogs; it

defaults to False for FileSelectionDialogs.

Since it is not always appropriate for a dialog box

to unmanage itself automatically, it turns out to be easier to set

XmNautoUnmanage to False in most circumstances. This

technique makes dialog management easier, since it keeps the toolkit

from indiscriminately dismissing a dialog simply because an action

button has been activated. While it is true that we could program

around this situation by calling XtPopup() or

XtManageChild() from a callback routine in error conditions, this

type of activity is confusing because of the double-negative action it

implies. In other words, programming around the situation is just

undoing something that should not have been done in the first place.

This discussion brings up some issues about when a

dialog should be unmanaged and when it should be destroyed. If you

expect the user to have an abundant supply of computer memory, you may

reuse a dialog by retaining a handle to the dialog, as shown in Example

5-4 later in this chapter. There are also performance considerations

that may affect whether you choose to destroy or reuse dialogs. It

takes less time to reuse a dialog than it does to create a new one,

provided that your application is not so large that it is consuming all

of the system's resources. If you do not retain a handle to a dialog,

and if you need to conserve memory and other resources, you should

destroy the dialog whenever you pop it down.

Another method the user might use to close a dialog is to select the Close item from the window menu. This menu can be pulled down from the title bar of a window. Since the menu belongs to the window manager, rather than the shell widget or the application, you cannot install any callback routines for its menu items. However, you can use the XmNdeleteResponse resource to control how the DialogShell responds to a Close action. The Motif VendorShell, from which the DialogShell is subclassed, is responsible for trapping the notification and determining what to do next, based on the value of the resource. It can have one of the following values:

It may be convenient for your application to know

when a dialog has been popped up or down. If so, you can install

callbacks that are invoked whenever either of these events take place.

The actions of popping up and down dialogs can be monitored through the

XmNpopupCallback and XmNpopdownCallback callback

routines. For example, when the function associated with a

XmNpopupCallback is invoked, you could position the dialog

automatically, rather than allowing the window manager to control the

placement. See Chapter 7, Custom Dialogs, for more information

on these callbacks.

Posting dialogs that display informative messages is

something just about every application is going to do frequently.

Rather than write a separate routine for each case where a message

needs to be displayed, we can generalize the process by writing a

single routine that handles most, if not all, cases. the source code

shows the PostDialog() routine. This routine creates a

MessageDialog of a given type and displays an arbitrary message. Rather

than use the convenience functions provided by Motif for each of the

MessageDialog types, the routine uses the generic function

XmCreateMessageDialog() and configures the symbol to be displayed

by setting the XmNdialogType resource.

XmStringCreateLocalized() is only available in Motif 1.2;

XmStringCreateSimple() is the corresponding function in Motif 1.1.

/*

* PostDialog() -- a generalized routine that allows the programmer

* to specify a dialog type (message, information, error, help, etc..),

* and the message to display.

*/

Widget

PostDialog(parent, dialog_type, msg)

Widget parent;

int dialog_type;

char *msg;

{

Widget dialog;

XmString text;

dialog = XmCreateMessageDialog (parent, "dialog", NULL, 0);

text = XmStringCreateLocalized (msg);

XtVaSetValues (dialog,

XmNdialogType, dialog_type,

XmNmessageString, text,

NULL);

XmStringFree (text);

XtManageChild (dialog);

XtPopup (XtParent (dialog), XtGrabNone);

return dialog;

}

This routine allows the programmer to specify several parameters: the

parent widget, the type of dialog that is to be used, and the message

that is to be displayed. The function returns the new dialog widget, so

that the calling routine can modify it, unmanage it, or keep a handle

to it. You may have additional requirements that this simplified

example does not satisfy. For instance, the routine does not allow you

to specify callback functions for the buttons in the action area and it

does not handle the destruction of the widget when it is no longer

needed. You could extend the routine to handle these issues, or you

could control them outside the context of the function. You may also

want to extend the routine so that it reuses the same dialog each time

it is called and so that it allows you to disable the different action

area buttons. All of these issues are discussed again in Chapter 6,

Selection Dialogs, and in Chapter 21, Advanced Dialog

Programming.

The following sections discuss resources that are

specific to Motif dialogs. In most cases, these resources are

BulletinBoard widget resources, since all Motif dialogs are subclassed

from this class. However, they are not intended to be used by generic

BulletinBoard widgets. The resources only apply when the widget is an

immediate child of a DialogShell widget; they are really intended to be

used exclusively by the predefined Motif dialog classes. Remember that

the resources must be set on the dialog widget, not the DialogShell.

See Chapter 8, Manager Widgets, for details on the generic

BulletinBoard resources.

All predefined Motif dialogs have a default

button in their action area. The default button is activated when

the user presses the RETURN key in the dialog. The OK button is

normally the default button, but once the dialog is displayed, the user

can change the default button by using the arrow keys to traverse the

action buttons. The action button with the keyboard focus is always the

default button. Since the default button can be changed by the user,

the button that is the default is only important when the dialog is

initially popped up. The importance of the default button lies in its

ability to influence the user's default response to the dialog.

You can change the default button for a MessageDialog by setting the XmNdefaultButtonType resource on the dialog widget. This resource is specific to MessageDialogs; it cannot be set for the various types of selection dialogs. The resource can have one of the following values:

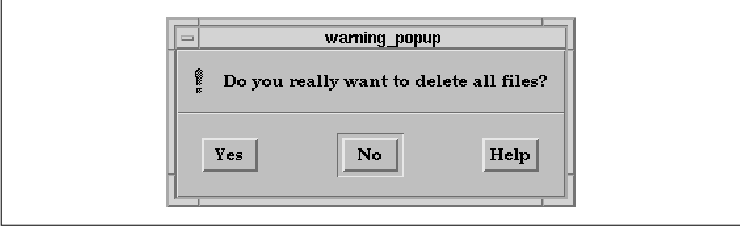

The values for XmNdefaultButtonType come up

again later, when we discuss XmMessageBoxGetChild() and again

in Chapter 6, Selection Dialogs, for

XmSelectionBoxGetChild(). An example of how the default button type

can be used is shown in the source code XmStringCreateLocalized()

is only available in Motif 1.2; XmStringCreateSimple() is the

corresponding function in Motif 1.1.

/*

* WarningMsg() -- Inform the user that she is about to embark on a

* dangerous mission and give her the opportunity to back out.

*/

void

WarningMsg(parent, client_data, call_data)

Widget parent;

XtPointer client_data;

XtPointer call_data;

{

static Widget dialog;

XmString text, ok_str, cancel_str;

char *msg = (char *) client_data;

if (!dialog)

dialog = XmCreateWarningDialog (parent, "warning", NULL, 0);

text = XmStringCreateLtoR (msg, XmFONTLIST_DEFAULT_TAG);

ok_str = XmStringCreateLocalized ("Yes");

cancel_str = XmStringCreateLocalized ("No");

XtVaSetValues (dialog,

XmNmessageString, text,

XmNokLabelString, ok_str,

XmNcancelLabelString, cancel_str,

XmNdefaultButtonType, XmDIALOG_CANCEL_BUTTON,

NULL);

XmStringFree (text);

XmStringFree (ok_str);

XmStringFree (cancel_str);

XtManageChild (dialog);

XtPopup (XtParent (dialog), XtGrabNone);

}

The intent of this function is to create a dialog that tries to

discourage the user from performing a destructive action. By using a

WarningDialog and by making the Cancel button the default

choice, we have given the user adequate warning that the action may

have dangerous consequences. The output of a program running this code

fragment is shown in the figure.

You can also set the default button for a dialog by

the setting the BulletinBoard resource XmNdefaultButton. This

technique works for both MessageDialogs and SelectionDialogs. The

resource value must be a widget ID, which means that you have to get a

handle to a subwidget in the dialog to set the resource. You can get

the handle to subwidgets using XmMessageBoxGetChild() or

XmSelectionBoxGetChild(). Since this method breaks the Motif dialog

abstraction, we describe it later in Section #sinternwid.

When a dialog widget is popped up, one of the

internal widgets in the dialog has the keyboard focus. This widget is

typically the default button for the dialog, which makes sense in most

cases. However, there are situations where it is appropriate for

another widget to have the initial keyboard focus. For example, when a

PromptDialog is popped up, it makes sense for the TextField to have the

keyboard focus so that the user can immediately start typing a

response.

In Motif 1.1, it is not easy to set the initial

keyboard focus in a dialog widget to anything other than a button in

the action area. Motif 1.2 has introduced the XmNinitialFocus

resource to deal with this situation. Since this resource is a Manager

widget resource, it can be used for both MessageDialogs and

SelectionDialogs, although it is normally only used for

SelectionDialogs. The resource specifies the subwidget that has the

keyboard focus the first time that the dialog is popped up. If the

dialog is popped down and popped up again later, it remembers the

widget that had the keyboard focus when it was popped down and that

widget is given the keyboard focus again. The resource value must again

be a widget ID. The default value of XmNinitialFocus for

MessageDialogs is the subwidget that is also the XmNdefaultButton

for the dialog. For SelectionDialogs, the text entry area is the

default value for the resource.

The XmNminimizeButtons resource controls

how the dialog sets the widths of the action area buttons. If the

resource is set to True, the width of each button is set so

that it is as small as possible while still enclosing the entire label,

which means that each button will have a different width. The default

value of False specifies that the width of each button is set

to the width of the widest button, so that all buttons have the same

width.

When a new shell widget is mapped to the screen, the

window manager creates its own window that contains the title bar,

resize handles, and other window decorations and makes the window of

the DialogShell the child of this new window. This technique is called

reparenting a window; it is only done by the window manager in order to

add window decorations to a shell window. The window manager reparents

instances of all of the shell widget classes except OverrideShell.

These shells are used for menus and thus should not have window manager

decorations.

Most window managers that reparent shell windows

display titles in the title bars of their windows. For predefined Motif

dialogs, the Motif toolkit sets the default title to the name of the

dialog widget with the string _popup appended. Since this

string is almost certainly not an appropriate title for the window, you

can change the title explicitly using the XmNdialogTitle

BulletinBoard resource. (Do not confuse this title with the message

displayed in MessageDialog, which is set by XmNmessageString.)

The value for XmNdialogTitle must be a compound string. The

BulletinBoard in turn sets the XmNtitle resource of the

DialogShell; the value of this resource is a regular C string.

So, you can set the title for a dialog window in one

of two ways. The following code fragment shows how to set the title

using the XmNdialogTitle resource:

XmString title_string;

title_string = XmStringCreateLocalized ("Dialog Box");

dialog = XmCreateMessageDialog (parent, "dialog_name", NULL, 0);

XtVaSetValues (dialog,

XmNdialogTitle, title_string,

NULL);

XmStringFree (title_string);

This technique requires creating a compound string. If you set the

XmNtitle resource directly on the DialogShell, you can use a

regular C string, as in the following code fragment:

dialog = XmCreateMessageDialog (parent, "dialog_name", NULL, 0);

XtVaSetValues (XtParent (dialog),

XmNtitle, "Dialog Box",

NULL);

While the latter method is easier and does not require creating and

freeing a compound string, it does break the abstraction of treating

the dialog as a single entity.

The XmNnoResize resource controls whether

or not the window manager allows the dialog to be resized. If the

resource is set to True, the window manager does not display

resize handles in the window manager frame for the dialog. The default

value of False specifies that the window manager should

provide resize handles. Since some dialogs cannot handle resize events

very well, you may find it better aesthetically to prevent the user

from resizing them.

This resource is an attribute of the BulletinBoard

widget, even though it only affects the shell widget parent of a dialog

widget. The resource is provided as a convenience to the programmer, so

that she is not required to get a handle to the DialogShell. The

resource only affects the presence of resize handles in the window

manager frame; it does not deal with other window manager controls. See

Chapter 16, Interacting With the Window Manager, for details on

how to specify the window manager controls for a DialogShell, or any

shell widget, directly.

The BulletinBoard widget provides resources that

enable you to specify the fonts that are used for all of the button,

Label, and Text widget descendants of the BulletinBoard. Since Motif

dialog widgets are subclassed from the BulletinBoard, you can use these

resources to make sure that the fonts that are used within a dialog are

consistent. The XmNbuttonFontList resource specifies the font

list that is used for all of the button descendants of the dialog. The

resource is set on the dialog widget itself, not on its individual

children. Similarly, the XmNlabelFontList resource is used to

set the font list for all of the Label descendants of the dialog and

XmNtextFontList is used for all of the Text and TextField

descendants.

If one of these resources is not set, the toolkit

determines the font list by searching up the widget hierarchy for an

ancestor that is a subclass of BulletinBoard, VendorShell, or

MenuShell. If an ancestor is found, the font list resource is set to

the value of that font list resource in the ancestor widget. See

Chapter 19, Compound Strings, for more information on font

lists.

You can override the XmNbuttonFontList,

XmNlabelFontList, and XmNtextFontList resources on a

per-widget basis by setting the XmNfontList resource directly

on individual widgets. Of course, you must break the dialog abstraction

and retrieve the widgets internal to the dialog itself to set this

resource. While we describe how to do this in the following section, we

do not recommend configuring dialogs down to this level of detail.

As mentioned earlier, the predefined Motif dialogs

have their own resources to reference the labels and callback routines

for the action area PushButtons. Instead of accessing the PushButton

widgets in the action area to install callbacks, you use the resources

XmNokCallback, XmNcancelCallback, and XmNhelpCallback

on the dialog widget itself. These callbacks correspond to each of the

three buttons, OK, Cancel, and Help.

Installing callbacks for a dialog is no different

than installing them for any other type of Motif widget; it may just

seem different because the dialog widgets contain so many subwidgets.

The following code fragment demonstrates the installation of simple

callback for all of the buttons in a MessageDialog:

...

dialog = XmCreateMessageDialog (w, "notice", NULL, 0);

...

XtAddCallback (dialog, XmNokCallback, ok_pushed, "Hi");

XtAddCallback (dialog, XmNcancelCallback, cancel_pushed, "Foo");

XtAddCallback (dialog, XmNhelpCallback, help_pushed, NULL);

XtManageChild (dialog);

...

/* ok_pushed() --the OK button was selected. */

void

ok_pushed(widget, client_data, call_data)

Widget widget;

XtPointer client_data;

XtPointer call_data; { char *message = (char *) client_data; printf ("OK was selected: %s0, message); } /* cancel_pushed() --the Cancel button was selected. */ void cancel_pushed(widget, client_data, call_data) Widget widget; XtPointer client_data;

XtPointer call_data; { char *message = (char *) client_data; printf ("Cancel was selected: %s0, message); } /* help_pushed() --the Help button was selected. */ void help_pushed(widget, client_data, call_data) Widget widget; XtPointer client_data;

XtPointer call_data; { printf ("Help was selected0);

} In this example, a dialog is created and callback routines for each

of the three responses are added using XtAddCallback(). We

also provide simple client data to demonstrate how the data is passed

to the callback routines. These callback routines simply print the fact

that they have been activated; the messages they print are taken from

the client data.

All of the dialog callback routines take three

parameters, just like any standard callback routine. The widget

parameter is the dialog widget that contains the button that was

selected; it is not the DialogShell widget or the PushButton that the

user selected from the action area. The second parameter is the

client_data, which is supplied to XtAddCallback(), and the

third is the call_data, which is provided by the internals of

the widget that invoked the callback.

The client_data parameter is of type

XtPointer, which means that you can pass arbitrary values to the

function, depending on what is necessary. However, you cannot pass a

float or a double value or an actual data structure. If

you need to pass such values, you must pass the address of the variable

or a pointer to the data structure. In keeping with the philosophy of

abstracting and generalizing code, you should use the client_data

parameter as much as possible because it eliminates the need for some

global variables and it keeps the structure of an application modular.

For the predefined Motif dialogs, the call_data

parameter is a pointer to a data structure that is filled in by the

dialog box when the callback is invoked. The data structure contains a

callback reason and the event that invoked the callback. The structure

is of type XmAnyCallbackStruct, which is declared as follows:

typedef struct {

int reason;

XEvent *event;

} XmAnyCallbackStruct;

The value of the reason field is an integer value that can be

any one of XmCR_HELP, XmCR_OK, or XmCR_CANCEL

. The value specifies the button that the user pressed in the dialog

box. The values for the reason field remain the same, no

matter how you change the button labels for a dialog. For example, you

can change the label for the OK button to say Help, using

the resource XmNokLabelString, but the reason

parameter will still be XmCR_OK when the button is activated.

Because the reason field provides

information about the user's response to the dialog in terms of the

button that was pushed, we can simplify the previous code fragment and

use one callback function for all of the possible actions. The callback

function can determine which button was selected by examining

reason. the source code demonstrates this simplification.

XtSetLanguageProc() is only available in X11R5; there is no

corresponding function in X11R4. XmStringCreateLocalized() is

only available in Motif 1.2; XmStringCreateSimple() is the

corresponding function in Motif 1.1.

/* reason.c -- examine the reason field of the callback structure

* passed as the call_data of the callback function. This field

* indicates which action area button in the dialog was pressed.

*/

#include <Xm/RowColumn.h>

#include <Xm/MessageB.h>

#include <Xm/PushB.h>

/* main() --create a pushbutton whose callback pops up a dialog box */

main(argc, argv)

char *argv[];

{

XtAppContext app;

Widget toplevel, rc, pb;

extern void pushed();

XtSetLanguageProc (NULL, NULL, NULL);

toplevel = XtVaAppInitialize (&app, "Demos", NULL, 0,

&argc, argv, NULL, NULL);

rc = XtVaCreateWidget ("rowcol", xmRowColumnWidgetClass, toplevel, NULL);

pb = XtVaCreateManagedWidget ("Hello",

xmPushButtonWidgetClass, rc, NULL);

XtAddCallback (pb, XmNactivateCallback, pushed, "Hello World");

pb = XtVaCreateManagedWidget ("Goodbye",

xmPushButtonWidgetClass, rc, NULL);

XtAddCallback (pb, XmNactivateCallback, pushed, "Goodbye World");

XtManageChild (rc);

XtRealizeWidget (toplevel);

XtAppMainLoop (app);

}

/* pushed() --the callback routine for the main app's pushbuttons.

* Create and popup a dialog box that has callback functions for

* the OK, Cancel and Help buttons.

*/

void

pushed(widget, client_data, call_data)

Widget widget;

XtPointer client_data;

XtPointer call_data;

{

static Widget dialog;

char *message = (char *) client_data;

XmString t = XmStringCreateLocalized (message);

/* See if we've already created this dialog -- if so,

* we don't need to create it again. Just set the message

* and manage it (repop it up).

*/

if (!dialog) {

extern void callback();

Arg args[5];

int n = 0;

XtSetArg (args[n], XmNautoUnmanage, False); n++;

dialog = XmCreateMessageDialog (widget, "notice", args, n);

XtAddCallback (dialog, XmNokCallback, callback, "Hi");

XtAddCallback (dialog, XmNcancelCallback, callback, "Foo");

XtAddCallback (dialog, XmNhelpCallback, callback, "Bar");

}

XtVaSetValues (dialog, XmNmessageString, t, NULL);

XmStringFree (t);

XtManageChild (dialog);

XtPopup (XtParent (dialog), XtGrabNone);

}

/* callback() --One of the dialog buttons was selected.

* Determine which one by examining the "reason" parameter.

*/

void

callback(widget, client_data, call_data)

Widget widget;

XtPointer client_data;

XtPointer call_data;

{

char *button;

char *message = (char *) client_data;

XmAnyCallbackStruct *cbs = (XmAnyCallbackStruct *) call_data;

switch (cbs->reason) {

case XmCR_OK : button = "OK"; break;

case XmCR_CANCEL : button = "Cancel"; break;

case XmCR_HELP : button = "Help";

}

printf ("%s was selected: %s0, button, message);

if (cbs->reason != XmCR_HELP) {

/* the ok and cancel buttons "close" the widget */

XtPopdown (XtParent (widget));

}

}

Another interesting change in this application is the way pushed()

determines if the dialog has already been created. By making the dialog

widget handle static to the pushed() callback

function, we retain a handle to this object across multiple button

presses. For each invocation of the callback, the dialog's message is

reset and it is popped up again.

Considering style guide issues again, it is

important to know when it is appropriate to dismiss a dialog. As noted

earlier, the toolkit automatically unmanages a dialog whenever any of

the action area buttons are activated, except for the Help

button. This behavior is controlled by XmNautoUnmanage, which

defaults to True. However, if you set this resource to

False, the callback routines for the buttons in the action area

have to control the behavior on their own. In the source code the

callback routine pops down the dialog when the reason is XmCR_OK

or XmCR_CANCEL, but not when it is XmCR_HELP.

As described earlier, Motif treats dialogs as if

they are single user-interface objects. However, there are times when

you need to break this abstraction and work with some of the individual

widgets that make up a dialog. This section describes how the dialog

convenience routines work, how to work directly with the DialogShell,

and how to access the widgets that are internal to dialogs.

The fact that Motif dialogs are self-sufficient does

not imply that they are black boxes that perform magic that you cannot

perform yourself. For example, the convenience routines for the

MessageDialog types follow these basic steps:

XmDIALOG_ERROR XmDIALOG_INFORMATION XmDIALOG_MESSAGE XmDIALOG_QUESTION XmDIALOG_TEMPLATE XmDIALOG_WARNING XmDIALOG_WORKINGThe type of the dialog does not affect the kind of widget that is created. The only thing the type affects is the graphical symbol that is displayed in the control area of the dialog. The convenience routines set the resource based on the routine that is called (e.g. XmCreateErrorDialog() sets the resource to XmDIALOG_ERROR ). The widget automatically sets the graphical symbol based on the dialog type. You can change the type of a dialog after it is created using XtVaSetValues(); modifying the type also changes the dialog symbol that is displayed.

The Motif dialog convenience routines create

DialogShells internally to support the single-object dialog

abstraction. With these routines, the toolkit is responsible for the

DialogShell, so the dialog widget uses its XmNdestroyCallback

to destroy its parent upon its own destruction. If the dialog is

unmapped or unmanaged, so is its DialogShell parent. The convenience

routines do not add any resources or call any functions to support the

special relationship between the dialog widget and the DialogShell,

since most of the code that handles the interaction is written into the

internals of the BulletinBoard.

As your programs become more complex, you may

eventually have to access the DialogShell parent of a dialog widget in

order to get certain things done. This section examines DialogShells as

independent widgets and describes how they are different from other

shell widgets. There are three main features of a DialogShell that

differentiate it from an ApplicationShell and a TopLevelShell.

The parent-child relationship between a DialogShell

and its parent is different from the classic case, where the parent

actually contains the child within its geometrical bounds. The

DialogShell widget is a popup child of its parent, which means that the

usual geometry-management relationship does not apply. Nonetheless, the

parent widget must be managed in order for the child to be displayed.

If a widget has popup children, those children are not mapped to the

screen if the parent is not managed, which means that you must never

make a menu item the parent of a DialogShell.

Assuming that the parent is displayed, the window

manager attempts to place the DialogShell based on the value of the

XmNdefaultPosition BulletinBoard resource. The default value of

this resource is True, which means that the window manager

positions the DialogShell so that it is centered on top of its parent.

If the resource is set to False, the application and the

window manager negotiate about where the dialog is placed. This

resource is only relevant when the BulletinBoard is the immediate child

of a DialogShell, which is always the case for Motif dialogs. If you

want, you can position the dialog by setting the XmNx and

XmNy resources for the dialog widget. Positioning the dialog on the

screen must be done through a XmNmapCallback routine, which is

called whenever the application calls XtManageChild(). See

Chapter 7, Custom Dialogs, for a discussion about dialog

positioning.

The Motif Window Manager imposes an additional

constraint on the stacking order of the DialogShell and its parent.

mwm always forces the DialogShell to be directly on top of its

parent in the stacking order. The result is that the shell that

contains the widget acting as the parent of the DialogShell cannot be

placed on top of the dialog. This behavior is defined by the Motif

Style Guide and is enforced by the Motif Window Manager and the

Motif toolkit. Many end-users have been known to report the behavior as

an application-design bug, so you may want to describe this behavior

explicitly in the documentation for your application, in order to

prepare the user ahead of time.

Internally, DialogShell widgets communicate

frequently with dialog widgets in order to support the single-entity

abstraction promoted by the Motif toolkit. However, you may find that

you need to access the DialogShell part of a Motif dialog in order to

query information from the shell or to perform certain actions on it.

The include file <Xm/DialogS.h> provides a convenient macro for

identifying whether or not a particular widget is a DialogShell:

#define XmIsDialogShell(w) XtIsSubclass(w, xmDialogShellWidgetClass)If you need to use this macro, or you want to create a DialogShell using XmCreateDialogShell(), you need to include < Xm/DialogS.h>.

The macro is useful if you want to determine whether

or not a dialog widget is the direct child of a DialogShell. For

example, earlier in this chapter, we mentioned that the Motif Style

Guide suggests that if the user activates the OK button in a

MessageDialog, the entire dialog should be popped down. If you have

created a MessageDialog without using XmCreateMessageDialog()

and you want to be sure that the same thing happens when the user

presses the OK button in that dialog, you need to test whether

or not the parent is a DialogShell before you pop down the dialog. The

following code fragment shows the use of the macro in this type of

situation:

/* traverse up widget tree till we find a window manager shell */

Widget

GetTopShell(widget)

Widget widget;

{

while (widget && !XmIsWMShell (widget))

widget = XtParent (widget));

return widget;

}

void

ok_callback(dialog, client_data, call_data)

Widget dialog;

XtPointer client_data;

XtPointer call_data;

{

/* do whatever the callback needs to do ... */

/* if immediate parent is not a DialogShell, mimic

the same * behavior as if it were (i.e., pop down the parent.) */ if

(!XmIsDialogShell (XtParent (dialog))) XtPopdown (GetTopShell

(dialog)); } The Motif toolkit defines similar macros for all of its

widget classes. For example, <Xm/MessageB.h> defines the macro

XmIsMessageBox():

#define XmIsMessageBox(w) XtIsSubclass (w, xmMessageBoxWidgetClass)This macro determines whether or not a particular widget is subclassed from the MessageBox widget class. Since all of the MessageDialogs are really instances of the MessageBox class, the macro covers all of the different types of MessageDialogs. If the widget is a MessageBox, the macro returns True whether or not the widget is an immediate child of a DialogShell. Note that this macro does not return True if the widget is a DialogShell.

All of the Motif dialog widgets are composed of

primitive subwidgets such as Labels, PushButtons, and TextField

widgets. For most tasks, it is possible to treat a dialog as a single

entity. However, there are some situations when it is useful to be able

to get a handle to the widgets internal to the dialog. For example, one

way to set the default button for a dialog is to use the

XmNdefaultButton resource. The value that you specify for this

resource must be a widget ID, so this is one of those times when it is

necessary to get a handle to the actual subwidgets contained within a

dialog.

The Motif toolkit provides routines that allow you

to access the internal widgets. For MessageDialogs, you can retrieve

the subwidgets using XmMessageBoxGetChild(), which has the

following form:

Widget

XmMessageBoxGetChild(widget, child)

Widget widget;

unsigned char child;

The widget parameter is a handle to a dialog widget,

not its DialogShell parent. The child parameter is an

enumerated value that specifies a particular subwidget in the dialog.

The parameter can have any one of the following values:

XmDIALOG_OK_BUTTON XmDIALOG_CANCEL_BUTTON XmDIALOG_HELP_BUTTON XmDIALOG_DEFAULT_BUTTON XmDIALOG_MESSAGE_LABEL XmDIALOG_SEPARATOR XmDIALOG_SYMBOL_LABELThe values refer to the different widgets in a MessageDialog and they should be self-explanatory. For SelectionDialogs, the toolkit provides the XmSelectionBoxGetChild() routine. This routine is identical to XmMessageBoxGetChild(), except that it takes different values for the different widgets in a SelectionDialog. The routine is discussed in Chapter 6, Selection Dialogs.

One method that you can use to customize the

predefined Motif dialogs is to unmanage the subwidgets that are

inappropriate for your purposes. To get the widget ID for a widget, so

that you can pass it to XtUnmanageChild(), you need to call

XmMessageBoxGetChild(). You can also use this routine to get a

handle to a widget that you want to temporarily disable. These

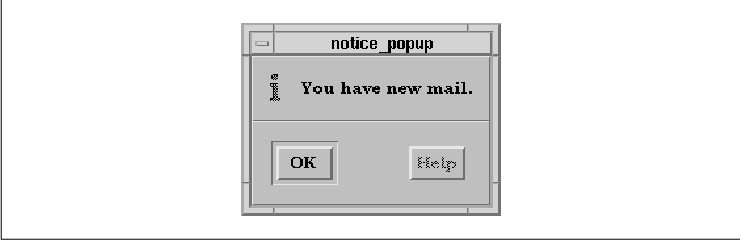

techniques are demonstrated in the following code fragment:

text = XmStringCreateLocalized ("You have new mail.");

XtSetArg (args[0], XmNmessageString, text);

dialog = XmCreateInformationDialog (parent, "message", args, 1);

XmStringFree (text);

XtSetSensitive (

XmMessageBoxGetChild (dialog, XmDIALOG_HELP_BUTTON), False);

XtUnmanageChild (

XmMessageBoxGetChild (dialog, XmDIALOG_CANCEL_BUTTON));

The output of a program using this code fragment is shown in the

figure.

Since the message in this dialog is so simple, it

does not make sense to have both an OK and a Cancel

button, so we unmanage the latter. On the other hand, it does make

sense to have a Help button. However, there is currently no help

available, so we make the button unselectable by desensitizing it using

XtSetSensitive().

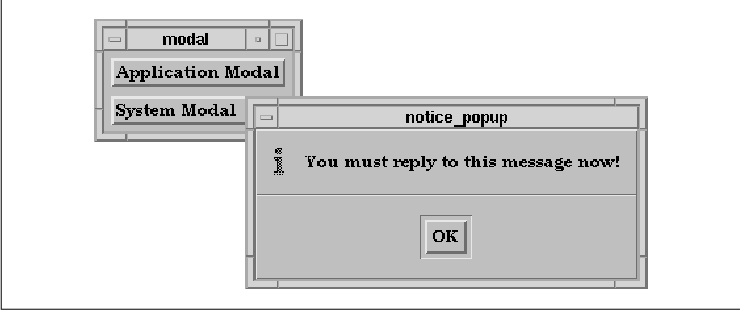

The concept of forcing the user to respond to a

dialog is known as modality. Modality governs whether or not the

user can interact with other windows on the desktop while a particular

dialog is active. Dialogs are either modal or modeless. There are three

levels of modality: primary application modal, full application modal,

and system modal. In all cases, the user must interact with a modal

dialog before control is released and normal input is resumed. In a

system modal dialog, the user is prevented from interacting with any

other window on the display. Full application modal dialogs allow the

user to interact with any window on the desktop except those that are

part of the same application as the modal window. Primary application

modal dialogs allow the user to interact with any other window on the

display except for the window that is acting as the parent for this

particular dialog.

For example, if the user selected an action that

caused an error dialog to be displayed, the dialog could be primary

application modal, so that the user would have to acknowledge the error

before she interacts with the same window again. This type of modality

does not restrict her ability to interact with another window in the

same application, provided that the other window is not the one acting

as the parent for the modal dialog.

Modal dialogs are perhaps the most frequently

misused feature of a graphical user interface. Programmers who fail to

grasp the concept of event-driven programming and design, whereby the

user is in control, often fall into the convenient escape route that

modal dialogs provide. This problem is difficult to detect, let alone

cure, because there are just as many right ways to invoke modal dialogs

as there are wrong ways. Modality should be used in moderation, but it

should also be used consistently. Let's examine a common scenario. Note

that this example does not necessarily favor using modal dialogs; it is

presented as a reference point for the types of things that people are

used to doing in tty-based programs.

A text editor has a function that allows the user to

save its text to a file. In order to save the text, the program needs a

filename. Once it has a filename, the program needs to check that the

user has sufficient permission to open or create the file and it also

needs to see if there is already some text in the file. If an error

condition occurs, the program needs to notify the user of the error,

ask for a new filename, or get permission to overwrite the file's

contents. Whatever the case, some interaction with the user is

necessary in order to proceed. If this were a typical terminal-based

application, the program flow would be similar to that in the following

code fragment:

FILE *fp;

char buf[BUFSIZ], file[BUFSIZ];

extern char *index();

printf ("What file would you like to use? ");

if (!(fgets (file, sizeof file, stdin)) || file[0] == 0) {

puts ("Cancelled.");

return;

}

*(index (file, '0)) = 0; /* get rid of newline terminator */

/* "a+" creates file if it doesn't exist */

if (!(fp = fopen (file, "a+"))) {

perror (file);

return;

}

if (ftell (fp) > 0) { /* There's junk in the file already */

printf ("Overwrite contents of %s? ", file);

buf[0] = 0;

if (!(fgets (buf, sizeof buf, stdin)) || buf[0] == 0 ||

buf[0] == 'n' || buf[0] == 'N') {

puts ("Cancelled.");

fclose (fp);

return;

}

}

rewind (fp);

This style of program flow is still possible with a graphical user

interface system using modal dialogs. In fact, the style is frequently

used by engineers who are trying to port tty-based applications to

Motif. It is also a logical approach to programming, since it does one

task followed by another, asking only for information that it needs

when it needs it.

However, in an event-driven environment, where the

user can interact with many different parts of the program

simultaneously, displaying a series of modal dialogs is not the best

way to handle input and frequently it's just plain wrong as a design

approach. You must adopt a new paradigm in interface design that

conforms to the capabilities of the window system and meets the

expectations of the user. It is essential that you understand the

event-driven model if you want to create well-written, easy-to-use

applications.

Window-based applications should be modeled on the

behavior of a person filling out a form, such as an employment

application or a medical questionnaire. Under this scenario, you are

given a form asking various questions. You take it to your seat and

fill it out however you choose. If it asks for your license number, you

can get out your driver's license and copy down the number. If it asks

for your checking account number, you can examine your checkbook for

that information. The order in which you fill out the application is

entirely up to you. You are free to examine the entire form and fill

out whatever portions you like, in whatever order you like.

When the form is complete, you return it to the

person who gave it to you. The attendant can check it over to see if

you forgot something. If there are errors, you typically take it back

and continue until it's right. The attendant can simply ask you the

question straight out and write down whatever you say, but this

prevents him from doing other work or dealing with other people.

Furthermore, if you don't know the answer to the question right away,

then you have to take the form back and fill it out the way you were

doing it before. No matter how you look at it, this process is not an

interview where you are asked questions in sequence and must answer

them that way. You are supposed to prepare the form off-line, without

requiring interaction from anyone else.

Window-based applications should be treated no

differently. Each window, or dialog, can be considered to be a form of

some sort. Allow the user to fill out the form at her own convenience

and however she chooses. If she wants to interact with other parts of

the application or other programs on the desktop, she should be allowed

to do so. When the user selects one of the buttons in the action area,

this action is her way of returning the form. At this time, you may

either accept it or reject it. At no point in the process so far have

we needed a modal dialog.

Once the form has been submitted, you can take

whatever action is appropriate. If there are errors in any section of

the dialog, you may need to notify the user of the error. Here is where

a modal dialog can be used legitimately. For example, if the user is

using a FileSelectionDialog to specify the file she wants to read and

the file is unreadable, then you must notify her so that she can make

another selection. In this case, the notification is usually in the

form of an ErrorDialog, with a message that explains the error and an

OK button. The user can read the message and press the button to

acknowledge the error.

It is often difficult to judge what types of

questions or how much information is appropriate in modal dialogs. The

rule of thumb is that questions in modal dialogs should be limited to

simple, yes/no questions. You should not prompt for any information

that is already available through an existing dialog, but instead bring

up that dialog and instruct the user to provide the necessary

information there. You should also avoid posting modal dialogs that

prompt for a filename or anything else that requires typing. You should

be requesting this type of information through the text fields of

modeless dialog boxes.

As for the issue of forcing the user to fill out

forms in a particular order, it may be perfectly reasonable to require

this type of interaction. You should implement these restrictions by

managing and unmanaging separate dialogs, rather than by using modal

dialogs to prevent interaction with all but a single dialog.

All of these admonitions are not to suggest that

modal dialogs are rare or that you should avoid using them at all

costs. On the contrary, they are extremely useful in certain

situations, are quite common, and are used in a wide variety of

ways--even those that we might not recommend. We have presented all of

these warnings because modal dialogs are frequently misused and

programs that use fewer of them are usually better than those that use

more of them. Modal dialogs interrupt the user and disrupt the flow of

work in an application. There is no sanity checking to prevent you from

misusing dialogs so it is up to you to keep the use of modal dialogs to

a minimum.

Once you have determined that you need to implement

a modal dialog, you can use the XmNdialogStyle resource to

set the modality of the dialog. This resource is defined by the

BulletinBoard widget class; it is only relevant when the widget is an