Chapter 2. Basic iPhone Styling

| If you know HTML, CSS, and JavaScript, you already have what you need to develop your own iPhone apps. With this book, you'll learn how to use these open source web technologies to design and build apps for both the iPhone and iPod Touch. Buy the print book or ebook or purchase the iPhone App. |

Ultimately, we are going to build a native iPhone app using HTML, CSS, and JavaScript. The first step on this journey is to get comfortable styling HTML to look like an iPhone app. In this chapter, I’ll show you how to apply CSS styles to a bunch of existing HTML pages so that they are easily navigable on an iPhone. So, in addition to moving closer to building a native app, you’ll be learning a practical (and valuable) skill that you can use immediately.

First Steps

Theory is great, but I’m a “show me, don’t tell me” kinda guy. So let’s dive in.

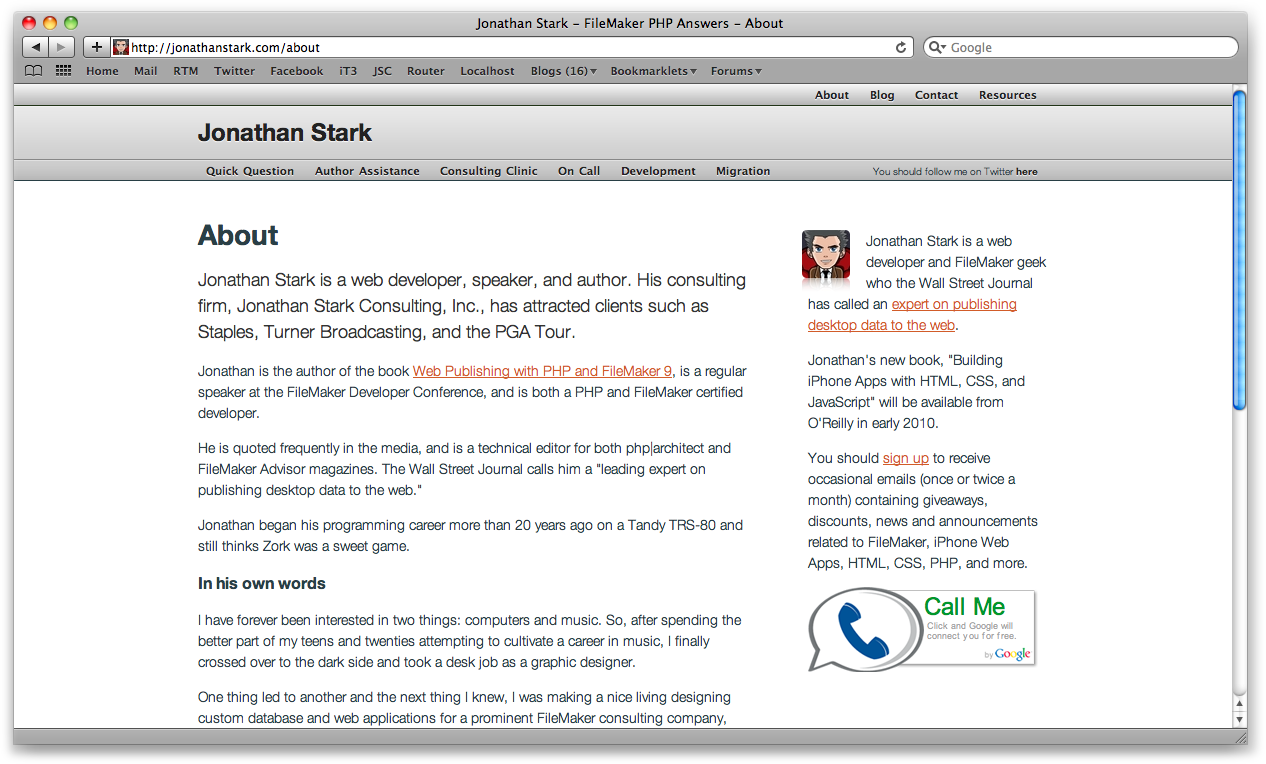

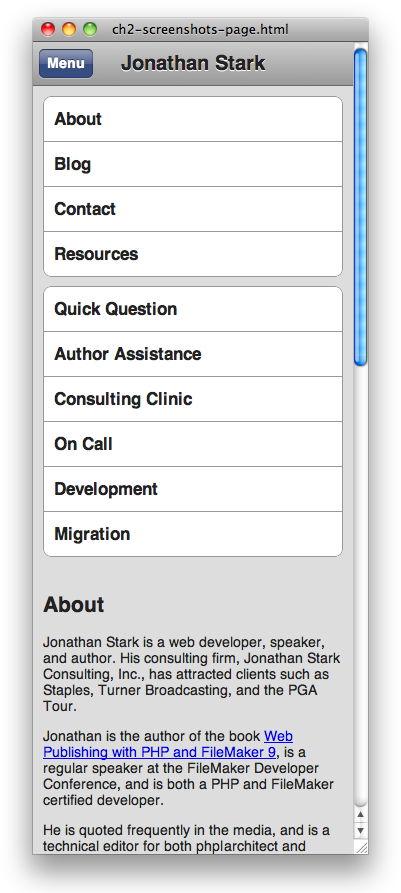

Imagine that you have a website that you want to iPhone-ize (Figure 2.1, “The desktop version of a typical web page looks fine in Safari on a computer”). In this scenario, there are a number of easy things you can do to optimize a site for the iPhone. I’ll go over your options in this chapter.

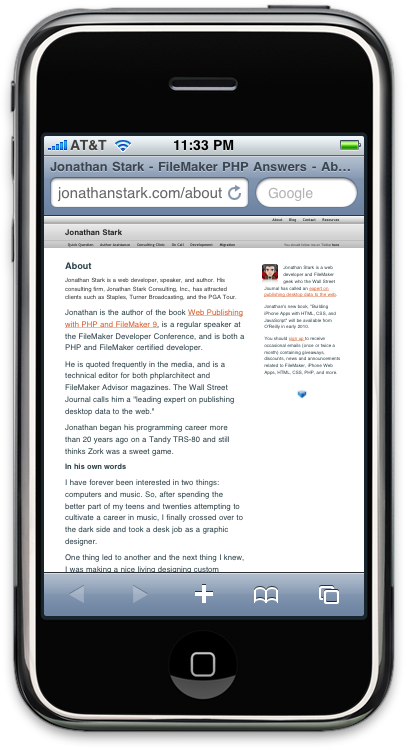

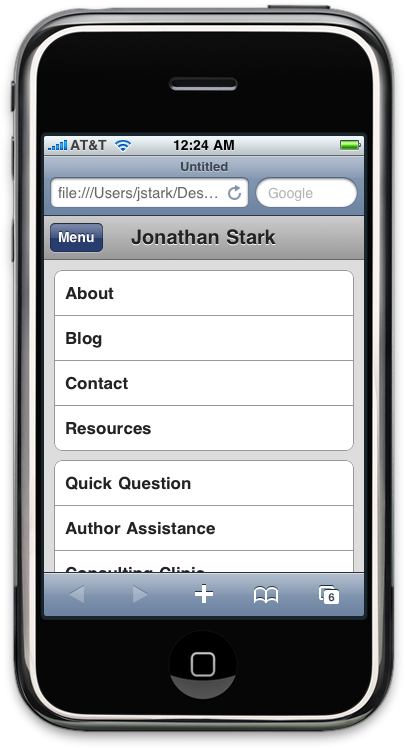

Figure 2.2, “The same web page looks OK on an iPhone, but we can do much better” shows what the same web page looks like on the iPhone. It’s usable, but far from optimized for the iPhone.

Example 2.1, “The HTML document we’ll be styling” shows an

abbreviated version of the HTML for the web page shown in Figure 2.1, “The desktop version of a typical web page looks fine in Safari on

a computer”. This is the HTML you’ll be working with

in this chapter. You can download it from the book’s website (see the section called “How to Contact Us”) if you’d like to try styling it as you go

through the chapter. The desktop stylesheet

(screen.css) is not shown, as it is not essential,

but you can use the stylesheet from the previous chapter if you’d like to

have something to play with.

Example 2.1. The HTML document we’ll be styling

<html>

<head>

<link rel="stylesheet" href="screen.css" type="text/css" />

<title>Jonathan Stark</title>

</head>

<body>

<div id="container">

<div id="header">

<h1><a href="./">Jonathan Stark</a></h1>

<div id="utility">

<ul>

<li><a href="about.html">About</a></li>

<li><a href="blog.html">Blog</a></li>

</ul>

</div>

<div id="nav">

<ul>

<li><a href="consulting-clinic.html">Consulting Clinic</a></li>

<li><a href="on-call.html">On Call</a></li>

<li><a href="development.html">Development</a></li>

</ul>

</div>

</div>

<div id="content">

<h2>About</h2>

<p>Jonathan Stark is a web developer, speaker, and author. His

consulting firm, Jonathan Stark Consulting, Inc., has attracted

clients such as Staples, Turner Broadcasting, and the PGA Tour.

...

</p>

</div>

<div id="sidebar">

<img alt="Manga Portrait of Jonathan Stark"

src="images/manga.png"

<p>Jonathan Stark is a mobile and web application developer who the

Wall Street Journal has called an expert on publishing desktop

data to the web.</p>

</div>

<div id="footer">

<ul>

<li><a href="services.html">Services</a></li>

<li><a href="about.html">About</a></li>

<li><a href="blog.html">Blog</a></li>

</ul>

<p class="subtle">Jonathan Stark Consulting, Inc.</p>

</div>

</div>

</body>

</html>Tip

For years, web developers used tables to lay

out elements in a grid. Advances in CSS and HTML have rendered that

approach not only obsolete, but undesirable. Today, we primarily use the

div element (along with a variety of attributes) to

accomplish the same thing, but with more control. Although a complete

explanation of div-based layouts is well beyond the

scope of this book, you’ll see plenty of examples of it as you read

through the chapters. To learn more, check out Designing with

Web Standards by Jeffrey Zeldman (New Riders Press), which

covers the issue in greater detail.

Preparing a Separate iPhone Stylesheet

I’m as DRY as the next guy, but in the real world you’re better off making a clean break between your desktop browser stylesheet and your iPhone stylesheet. Take my word for it and make two completely independent files—you’ll sleep better. The alternative would be to wedge all of your CSS rules into a single stylesheet, which ends up being a bad idea for a number of reasons; the most obvious is that you’d be sending a bunch of irrelevant desktop style rules to the phone, which is a waste of precious bandwidth and memory.

Note

DRY stands for “Don’t Repeat Yourself,” and is a software development principle stating that “Every piece of knowledge must have a single, unambiguous, authoritative representation within a system.” The term was coined by Andrew Hunt and David Thomas in their book The Pragmatic Programmer (Addison-Wesley).

To specify a stylesheet for the iPhone, replace the stylesheet link tag in the sample HTML document with ones that use the following expressions:

<link rel="stylesheet" type="text/css"

href="iphone.css" media="only screen and (max-width: 480px)" />

<link rel="stylesheet" type="text/css"

href="desktop.css" media="screen and (min-width: 481px)" />Here, desktop.css refers

to whatever your existing desktop stylesheet is, and

iphone.css is a new file that we’ll be discussing

in detail in a bit.

Note

If you’re following along using the sample

HTML document shown earlier, you’ll now need to rename

screen.css to desktop.css; however, since we’re

focused on the iPhone stylesheet, you can ignore the desktop

stylesheet completely. If it fails to load, your browser won’t get too

upset.

Regrettably, Internet Explorer will not understand the previous expressions, so we have to add a conditional comment (shown in bold) that links to an IE-specific version of the CSS:

<link rel="stylesheet" type="text/css"

href="iphone.css" media="only screen and (max-width: 480px)" />

<link rel="stylesheet" type="text/css"

href="desktop.css" media="screen and (min-width: 481px)" />

<!--[if IE]>

<link rel="stylesheet" type="text/css" href="explorer.css" media="all" />

<![endif]-->So now it’s time to edit the HTML document:

delete the existing link to the

screen.css file and replace it with the lines just

shown. This way, you will have a clean slate for the iPhone-specific CSS

that I’ll show you in this chapter.

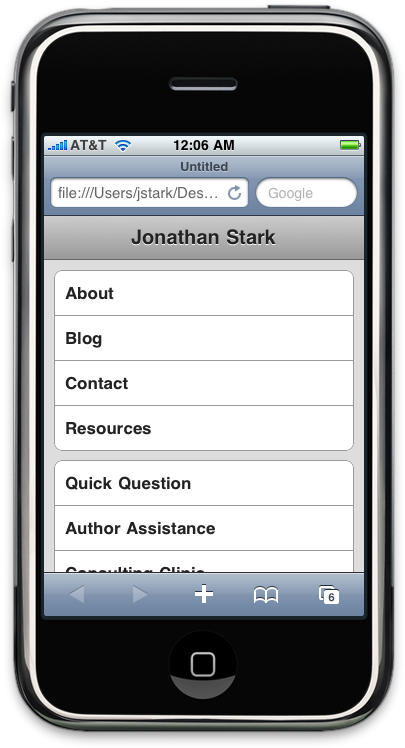

Controlling the Page Scaling

Unless you tell it otherwise, Safari on the iPhone is going to assume that your page is 980px

wide (Figure 2.3, “The iPhone assumes a normal web page is 980px wide”). In the majority of cases, this

works great. However, you are going to format our content specifically

for the smaller dimensions of the iPhone, so you must let Mobile Safari

know about it by adding a viewport meta tag to the head element of the HTML

document:

<meta name="viewport" content="user-scalable=no, width=device-width" />

If you don’t set the viewport width, the page will be zoomed way out when it first loads.

Note

The viewport meta tag will be ignored by browsers other than Mobile Safari, so you can include it without worrying about the desktop version of your site.

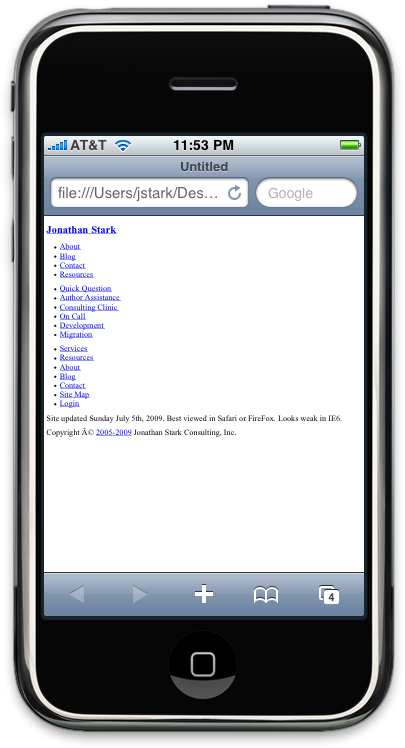

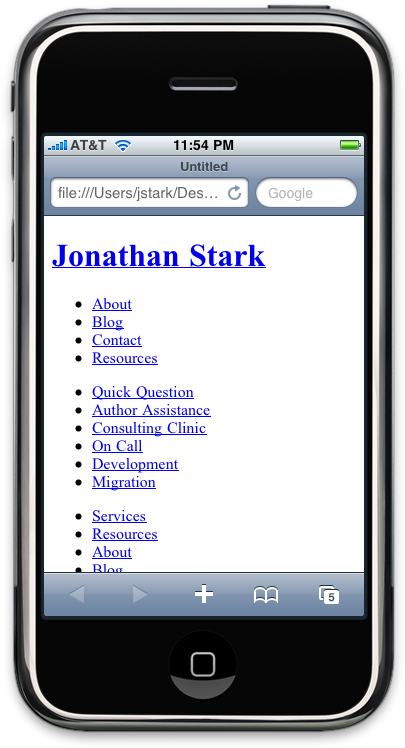

Merely by suppressing the desktop stylesheet

and configuring your viewport, you are already giving your iPhone users

an enhanced experience (Figure 2.4, “Setting the viewport to the width of the device makes your

pages a lot more readable”). To really impress

them, let’s start building the iphone.css

stylesheet.

Adding the iPhone CSS

There are a number of user interface (UI) conventions that make an iPhone app look like an iPhone

app. In the next section, I’ll add the distinctive title bar, lists with

rounded corners, finger-friendly links that look like glossy buttons, and

so on. Using your text editor, create a file named

iphone.css, add the code in Example 2.2, “Setting some general site-wide styles on the HTML body

element”, and save the file in the same

directory as your HTML document.

Example 2.2. Setting some general site-wide styles on the HTML body element

body {

background-color: #ddd; /* Background color */

color: #222; /* Foreground color used for text */

font-family: Helvetica;

font-size: 14px;

margin: 0; /* Amount of negative space around the outside of the body */

padding: 0; /* Amount of negative space around the inside of the body */

}Tip

Note that I have set the overall font for the document to Helvetica, which is the font used by most of the applications on the iPhone. If you are trying to achieve a professional look, you should probably stick with Helvetica unless you have a specific reason not to.

Now I’ll attack the header

div that contains the main home link (i.e., the logo

link) and the primary and secondary site navigation. The first step is to

format the logo link as a clickable title bar. Add the following to the

iphone.css file:

#header h1 {

margin: 0;

padding: 0;

}

#header h1 a {

background-color: #ccc;

border-bottom: 1px solid #666;

color: #222;

display: block;

font-size: 20px;

font-weight: bold;

padding: 10px 0;

text-align: center;

text-decoration: none;

}I’m going to format

the primary and secondary navigation ul blocks identically,

so I can just use the generic tag selectors (i.e., #header

ul) as opposed to the tag ids (i.e.,

#header ul#utility, #header ul#nav):

#header ul {

list-style: none;

margin: 10px;

padding: 0;

}

#header ul li a {

background-color: #FFFFFF;

border: 1px solid #999999;

color: #222222;

display: block;

font-size: 17px;

font-weight: bold;

margin-bottom: -1px;

padding: 12px 10px;

text-decoration: none;

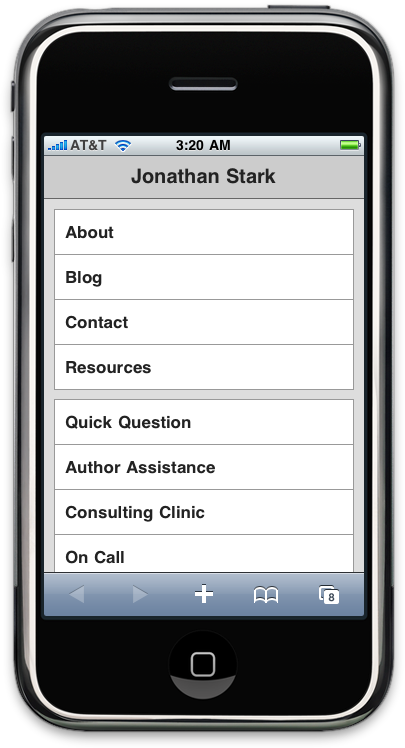

}Pretty simple so far, right? With this little

bit of CSS, we have already made a big improvement on the iPhone page

design (Figure 2.5, “A little bit of CSS can go a long way toward enhancing the

usability of your iPhone app”). Next, add some padding to the

content and sidebar divs to indent the text from the

edge of the screen a bit (Figure 2.6, “Indenting text from the edges”):

#content, #sidebar {

padding: 10px;

}Tip

You might be wondering why I added padding to the content and sidebar elements instead of setting it globally on the body element itself. The reason is that it’s very common to have elements that you want to have displayed edge to edge (as with the header in this example). Because of this, padding applied to the body or some other global wrapper element can become more trouble than it’s worth.

The content in the footer of this page is

basically a rehash of the navigation element at the top of the page (the

ul element with the id nav), so you can remove

the footer from the iPhone version of the page by setting the display to

none:

#footer {

display: none;

}Adding the iPhone Look and Feel

Now it’s time to get a little fancier. Starting from the top of the page, add a 1-pixel white drop shadow to the logo link text, and a CSS gradient to the background:

#header h1 a {

text-shadow: 0px 1px 0px #fff;

background-image: -webkit-gradient(linear, left top, left bottom,

from(#ccc), to(#999));

}In the text-shadow

declaration, the parameters from left to right are horizontal offset,

vertical offset, blur, and color. Most of the time, you’ll be applying the

exact values shown here to your text because that’s what usually looks

good on the iPhone, but it is fun to experiment with

text-shadow because it can add a subtle but

sophisticated touch to your design.

The -webkit-gradient line

deserves special attention. It’s an instruction to the

browser to generate a gradient image on the fly. Therefore, a CSS gradient

can be used anywhere you would normally specify a url()

(e.g., background image, list style image). The parameters from left to

right are as follows: the gradient type (can be linear or radial), the

starting point of the gradient (can be left top, left bottom, right top,

or right bottom), the end point of the gradient, the starting color, and

the ending color.

Tip

Note that you cannot reverse the horizontal and vertical portions of the four gradient start and stop point constants (i.e., left top, left bottom, right top, and right bottom). In other words, top left, bottom left, top right, and bottom right are invalid values.

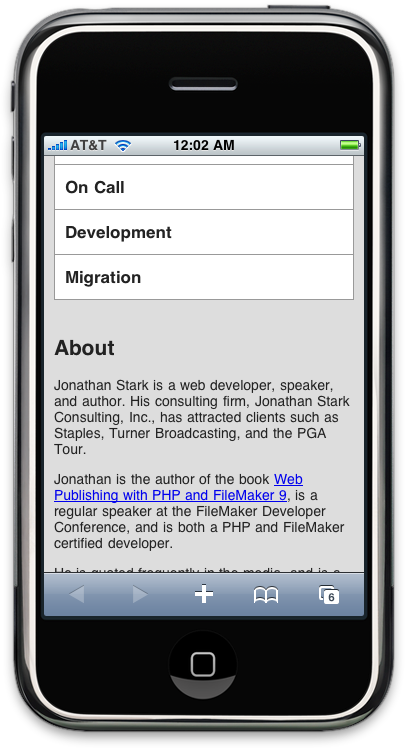

The next step is to add the traditional rounded corners to the navigation menus:

#header ul li:first-child a {

-webkit-border-top-left-radius: 8px;

-webkit-border-top-right-radius: 8px;

}

#header ul li:last-child a {

-webkit-border-bottom-left-radius: 8px;

-webkit-border-bottom-right-radius: 8px;

}As you can see, I’m using corner-specific

versions of the -webkit-border-radius property to apply an 8-pixel radius to both the top two

corners of the first list item, and the bottom two corners of the last

list item (Figure 2.7, “Gradients, text shadows, and rounded corners start to transform

your web page into a native-looking iPhone app”).

Figure 2.7. Gradients, text shadows, and rounded corners start to transform your web page into a native-looking iPhone app

It would be cool if you could just apply the

border radius to the enclosing ul, but it doesn’t work. If

you try it, you’ll see that the square corners of the child list items

will overflow the rounded corners of the ul, thereby negating

the effect.

Note

Technically, I could achieve the rounded list

effect by applying the radius corners to the ul if I set

the background color of the ul to white and the background

of its child elements to transparent. However, when you click the first

or last item in the list, the tap highlight will show up squared off and

it looks terrible. Your best bet is to apply the rounding to the tags

themselves as I’ve demonstrated here.

Adding Basic Behavior with jQuery

One of my favorite things about building web apps for the iPhone is that I can be reasonably sure that JavaScript is enabled. Regrettably, this is not the situation when building websites for desktop browsers. My next step is to add some JavaScript to my page to support some basic dynamic behavior. In particular, I want to allow users to show and hide the big honking navigation section in the header so that they only see it when they want to. In order to make this work, I’m going to write some new CSS, and use some JavaScript to apply the new CSS to the existing HTML.

First, let’s take a look at the new CSS. Step

one is to hide the ul elements in the header so they don’t show up when the user first

loads the page. If you are following along at home, open your

iphone.css file and add the following:

#header ul.hide {

display: none;

}Next, I’ll define the styles for the button that will show and hide the menu. Note that the button does not exist in the HTML yet; for your information, the HTML for the button is going to look like this:

<div class="leftButton" onclick="toggleMenu()">Menu</div>

I’ll describe the button HTML in detail in a

moment (the section called “Adding Basic Behavior with jQuery”), so don’t bother adding the

preceding line of code to your HTML file yet. The important thing to note

is that it’s a div with the class leftButton and

it’s going to be in the header.

Here is the CSS style for the button (you can

go ahead and add this to the iphone.css file):

#header div.leftButton {

position: absolute; top: 7px;

left: 6px;

height: 30px;

top: 7px;

left: 6px;

height: 30px; font-weight: bold;

font-weight: bold; text-align: center;

color: white;

text-shadow: rgba(0,0,0,0.6) 0px -1px 0px;

text-align: center;

color: white;

text-shadow: rgba(0,0,0,0.6) 0px -1px 0px; line-height: 28px;

line-height: 28px; border-width: 0 8px 0 8px;

border-width: 0 8px 0 8px; -webkit-border-image: url(images/button.png) 0 8 0 8;

-webkit-border-image: url(images/button.png) 0 8 0 8; }

}Tip

OK, time for some JavaScript. In preparation

for the JavaScript you’re about to write, you need to update your HTML

document to include jquery.js and

iphone.js. Add these lines to the head

section of your HTML document:

<script type="text/javascript" src="jquery.js"></script> <script type="text/javascript" src="iphone.js"></script>

Note

jQuery downloads, documentation, and

tutorials are available at http://jquery.com. To

use jQuery, you will need to download it from the website, rename the

file you downloaded (such as jquery-1.3.2.min.js)

to jquery.js, and put a copy of it in the same

directory as your HTML document.

The primary duty of the JavaScript we need to

write is to allow the user to show and hide the navigation menus. Copy the

following JavaScript into a file called iphone.js and

save it in the same folder as the HTML file:

if (window.innerWidth && window.innerWidth <= 480) {$(document).ready(function(){

$('#header ul').addClass('hide');

$('#header').append('<div class="leftButton" onclick="toggleMenu()">Menu</div>');

}); function toggleMenu() { $('#header ul').toggleClass('hide');

$('#header .leftButton').toggleClass('pressed');

} }

The entire page is wrapped in an

CautionIf you are testing your iPhone web pages using the

desktop version of Safari as described in Don’t Have a Website?,

the

You can even increase the height measurement to make a tall skinny view which is sometimes helpful if you are working with a lot of content (Figure 2.10, “A tall view of the completed basic iPhone CSS”, shown later). | |

Here we have the so-called “document ready” function. If you are new to jQuery, this can be a bit intimidating, and I admit that it took me a while to memorize the syntax. However, it’s worth taking the time to commit it to memory because you’ll be using it a lot. The document ready function basically says, “When the document is ready, run this code.” More on why this is important in a sec. | |

This is typical jQuery code that begins by

selecting the | |

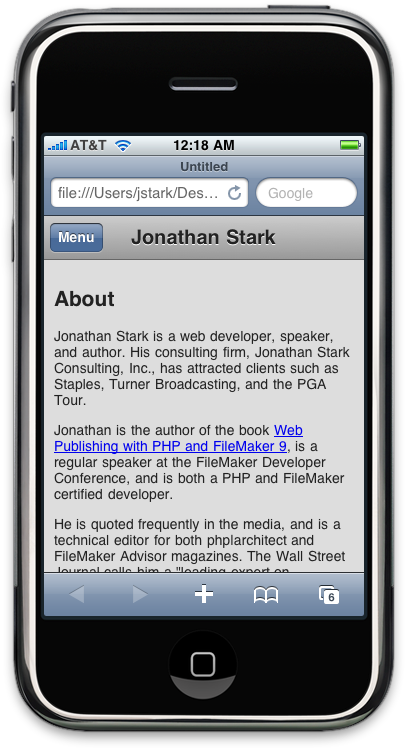

Here is where I append a button to the

header that will allow the user to show and hide the menu (Figure 2.8, “The Menu button has been added to the toolbar dynamically using

jQuery”). It has a class that

corresponds to the CSS we wrote previously for

| |

The | |

Here, I’m toggling the |

We haven’t written the CSS for the

pressed class yet, so let’s do so now. Go back to

iphone.css and insert the following:

#header div.pressed {

-webkit-border-image: url(images/button_clicked.png) 0 8 0 8;

}As you can see, I’m simply specifying a different image for the button border (it happens to be slightly darker). This will add a two-state effect to the button that should make it evident to the user that the button can both show and hide the menu (Figure 2.9, “The Menu button displays darker when it has been pressed to display the menu options”).

What You’ve Learned

In this chapter, I covered the basics of converting an existing web page to a more iPhone-friendly format. I even used a bit of dynamic HTML to show and hide the navigation panels. In the next chapter, I’ll build on these examples while introducing some more advanced JavaScript concepts—in particular, some yummy Ajax goodness.