|

Every process has an environment associated with it. An environment is a collection of environment variables. A variable is a changeable value with a fixed name. For example, the name EMAIL could refer to the value joe@nowhere.com. The value can vary; EMAIL could also refer to jane@somewhere.com.

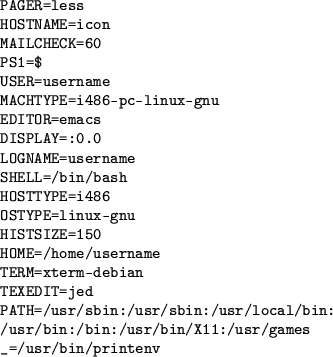

Because your shell is a process like any other, it has an environment. You can view your shell's environment by entering the printenv command.

Figure 6.1 on page![[*]](cross_ref_motif.png) has some sample output from printenv. On your system, the output will

be different but similar.

has some sample output from printenv. On your system, the output will

be different but similar.

Environment variables are one way to configure the system. For example, the EDITOR variable lets you select your preferred editor for posting news, writing e-mail, and so on.

Setting environment variables is simple. For practice, try customizing your shell's prompt and your text file viewer with environment variables. First, let's get a bit of background information.

Go ahead and glance over the man page for less, which is an enhanced pager. Scroll to a new page by pressing space; press q to quit. more will also quit automatically when you reach the end of the man page.

The command to set an environment variable within bash always has this format:

less has lots of features that more lacks. For example, you can scroll backward with the b key. You can also move up and down (even sideways) with the arrow keys. less won't exit when it reaches the end of the man page; it will wait for you to press q.

You can try out some less-specific commands, like b, to verify that they don't work with more and that you are indeed using more.

export is not necessary, because you're changing the shell's own behavior. There's no reason to export the variable into the environment for other programs to see. Technically, PS1 is a shell variable rather than an environment variable.

If you wanted to, you could export the shell variable, transforming it into an environment variable. If you do this, programs you run from the shell can see it.