|

|

|

|

|

|

|

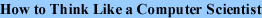

I haven't said much about it, but it is legal in C++ to make more than one assignment to the same variable. The effect of the second assignment is to replace the old value of the variable with a new value.

int fred = 5;The output of this program is 57, because the first time we print fred his value is 5, and the second time his value is 7.

This kind of multiple assignment is the reason I described variables as a container for values. When you assign a value to a variable, you change the contents of the container, as shown in the figure:

When there are multiple assignments to a variable, it is especially important to distinguish between an assignment statement and a statement of equality. Because C++ uses the = symbol for assignment, it is tempting to interpret a statement like a = b as a statement of equality. It is not!

First of all, equality is commutative, and assignment is not. For example, in mathematics if a = 7 then 7 = a. But in C++ the statement a = 7; is legal, and 7 = a; is not.

Furthermore, in mathematics, a statement of equality is true for all time. If a = b now, then a will always equal b. In C++, an assignment statement can make two variables equal, but they don't have to stay that way!

int a = 5;The third line changes the value of a but it does not change the value of b, and so they are no longer equal. In many programming languages an alternate symbol is used for assignment, such as <- or :=, in order to avoid confusion.

Although multiple assignment is frequently useful, you should use it with caution. If the values of variables are changing constantly in different parts of the program, it can make the code difficult to read and debug.

One of the things computers are often used for is the automation of repetitive tasks. Repeating identical or similar tasks without making errors is something that computers do well and people do poorly.

We have seen programs that use recursion to perform repetition, such as nLines and countdown. This type of repetition is called iteration, and C++ provides several language features that make it easier to write iterative programs.

The two features we are going to look at are the while statement and the for statement.

Using a while statement, we can rewrite countdown:

void countdown (int n) {You can almost read a while statement as if it were English. What this means is, "While n is greater than zero, continue displaying the value of n and then reducing the value of n by 1. When you get to zero, output the word `Blastoff!"'

More formally, the flow of execution for a while statement is as follows:

This type of flow is called a loop because the third step loops back around to the top. Notice that if the condition is false the first time through the loop, the statements inside the loop are never executed. The statements inside the loop are called the body of the loop.

The body of the loop should change the value of one or more variables so that, eventually, the condition becomes false and the loop terminates. Otherwise the loop will repeat forever, which is called an infinite loop. An endless source of amusement for computer scientists is the observation that the directions on shampoo, "Lather, rinse, repeat," are an infinite loop.

In the case of countdown, we can prove that the loop will terminate because we know that the value of n is finite, and we can see that the value of n gets smaller each time through the loop (each iteration), so eventually we have to get to zero. In other cases it is not so easy to tell:

void sequence (int n) {The condition for this loop is n != 1, so the loop will continue until n is 1, which will make the condition false.

At each iteration, the program outputs the value of n and then checks whether it is even or odd. If it is even, the value of n is divided by two. If it is odd, the value is replaced by 3n+1. For example, if the starting value (the argument passed to sequence) is 3, the resulting sequence is 3, 10, 5, 16, 8, 4, 2, 1.

Since n sometimes increases and sometimes decreases, there is no obvious proof that n will ever reach 1, or that the program will terminate. For some particular values of n, we can prove termination. For example, if the starting value is a power of two, then the value of n will be even every time through the loop, until we get to 1. The previous example ends with such a sequence, starting with 16.

Particular values aside, the interesting question is whether we can prove that this program terminates for all values of n. So far, no one has been able to prove it or disprove it!

One of the things loops are good for is generating tabular data. For example, before computers were readily available, people had to calculate logarithms, sines and cosines, and other common mathematical functions by hand. To make that easier, there were books containing long tables where you could find the values of various functions. Creating these tables was slow and boring, and the result tended to be full of errors.

When computers appeared on the scene, one of the initial reactions was, "This is great! We can use the computers to generate the tables, so there will be no errors." That turned out to be true (mostly), but shortsighted. Soon thereafter computers and calculators were so pervasive that the tables became obsolete.

Well, almost. It turns out that for some operations, computers use tables of values to get an approximate answer, and then perform computations to improve the approximation. In some cases, there have been errors in the underlying tables, most famously in the table the original Intel Pentium used to perform floating-point division.

Although a "log table" is not as useful as it once was, it still makes a good example of iteration. The following program outputs a sequence of values in the left column and their logarithms in the right column:

double x = 1.0;The sequence \verb+\t+ represents a tab character. The sequence \verb+\n+ represents a newline character. These sequences can be included anywhere in a string, although in these examples the sequence is the whole string.

A tab character causes the cursor to shift to the right until it reaches one of the tab stops, which are normally every eight characters. As we will see in a minute, tabs are useful for making columns of text line up.

A newline character has exactly the same effect as endl; it causes the cursor to move on to the next line. Usually if a newline character appears by itself, I use endl, but if it appears as part of a string, I use \verb+\n+.

The output of this program is

1 0If these values seem odd, remember that the log function uses base e. Since powers of two are so important in computer science, we often want to find logarithms with respect to base 2. To do that, we can use the following formula:

\[ \log_2 x = \frac {log_e x}{log_e 2} \]

Changing the output statement to

cout << x << "\t" << log(x) / log(2.0) << endl;yields

1 0We can see that 1, 2, 4 and 8 are powers of two, because their logarithms base 2 are round numbers. If we wanted to find the logarithms of other powers of two, we could modify the program like this:

double x = 1.0;Now instead of adding something to x each time through the loop, which yields an arithmetic sequence, we multiply x by something, yielding a geometric sequence. The result is:

1 0Because we are using tab characters between the columns, the position of the second column does not depend on the number of digits in the first column.

Log tables may not be useful any more, but for computer scientists, knowing the powers of two is! As an exercise, modify this program so that it outputs the powers of two up to 65536 (that's 216). Print it out and memorize it.

A two-dimensional table is a table where you choose a row and a column and read the value at the intersection. A multiplication table is a good example. Let's say you wanted to print a multiplication table for the values from 1 to 6.

A good way to start is to write a simple loop that prints the multiples of 2, all on one line.

int i = 1;The first line initializes a variable named i, which is going to act as a counter, or loop variable. As the loop executes, the value of i increases from 1 to 6, and then when i is 7, the loop terminates. Each time through the loop, we print the value 2*i followed by three spaces. By omitting the endl from the first output statement, we get all the output on a single line.

The output of this program is:

2 4 6 8 10 12So far, so good. The next step is to encapsulate and generalize.

Encapsulation usually means taking a piece of code and wrapping it up in a function, allowing you to take advantage of all the things functions are good for. We have seen two examples of encapsulation, when we wrote printParity in Section 4.3 and isSingleDigit in Section 5.8.

Generalization means taking something specific, like printing multiples of 2, and making it more general, like printing the multiples of any integer.

Here's a function that encapsulates the loop from the previous section and generalizes it to print multiples of n.

void printMultiples (int n)To encapsulate, all I had to do was add the first line, which declares the name, parameter, and return type. To generalize, all I had to do was replace the value 2 with the parameter n.

If we call this function with the argument 2, we get the same output as before. With argument 3, the output is:

3 6 9 12 15 18and with argument 4, the output is

4 8 12 16 20 24By now you can probably guess how we are going to print a multiplication table: we'll call printMultiples repeatedly with different arguments. In fact, we are going to use another loop to iterate through the rows.

int i = 1;First of all, notice how similar this loop is to the one inside printMultiples. All I did was replace the print statement with a function call.

The output of this program is

1 2 3 4 5 6which is a (slightly sloppy) multiplication table. If the sloppiness bothers you, try replacing the spaces between columns with tab characters and see what you get.

In the last section I mentioned "all the things functions are good for." About this time, you might be wondering what exactly those things are. Here are some of the reasons functions are useful:

To demonstrate encapsulation again, I'll take the code from the previous section and wrap it up in a function:

void printMultTable () {The process I am demonstrating is a common development plan. You develop code gradually by adding lines to main or someplace else, and then when you get it working, you extract it and wrap it up in a function.

The reason this is useful is that you sometimes don't know when you start writing exactly how to divide the program into functions. This approach lets you design as you go along.

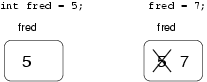

About this time, you might be wondering how we can use the same variable i in both printMultiples and printMultTable. Didn't I say that you can only declare a variable once? And doesn't it cause problems when one of the functions changes the value of the variable?

The answer to both questions is "no," because the i in printMultiples and the i in printMultTable are not the same variable. They have the same name, but they do not refer to the same storage location, and changing the value of one of them has no effect on the other.

Remember that variables that are declared inside a function definition are local. You cannot access a local variable from outside its "home" function, and you are free to have multiple variables with the same name, as long as they are not in the same function.

The stack diagram for this program shows clearly that the two variables named i are not in the same storage location. They can have different values, and changing one does not affect the other.

Notice that the value of the parameter n in printMultiples has to be the same as the value of i in printMultTable. On the other hand, the value of i in printMultiple goes from 1 up to n. In the diagram, it happens to be 3. The next time through the loop it will be 4.

It is often a good idea to use different variable names in different functions, to avoid confusion, but there are good reasons to reuse names. For example, it is common to use the names i, j and k as loop variables. If you avoid using them in one function just because you used them somewhere else, you will probably make the program harder to read.

As another example of generalization, imagine you wanted a program that would print a multiplication table of any size, not just the 6x6 table. You could add a parameter to printMultTable:

void printMultTable (int high) {I replaced the value 6 with the parameter high. If I call printMultTable with the argument 7, I get

1 2 3 4 5 6which is fine, except that I probably want the table to be square (same number of rows and columns), which means I have to add another parameter to printMultiples, to specify how many columns the table should have.

Just to be annoying, I will also call this parameter high, demonstrating that different functions can have parameters with the same name (just like local variables):

void printMultiples (int n, int high) {Notice that when I added a new parameter, I had to change the first line of the function (the interface or prototype), and I also had to change the place where the function is called in printMultTable. As expected, this program generates a square 7x7 table:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7When you generalize a function appropriately, you often find that the resulting program has capabilities you did not intend. For example, you might notice that the multiplication table is symmetric, because ab = ba, so all the entries in the table appear twice. You could save ink by printing only half the table. To do that, you only have to change one line of printMultTable. Change

printMultiples (i, high);to

printMultiples (i, i);and you get

1I'll leave it up to you to figure out how it works.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|