The above method of finding the frequency response involves physically measuring the amplitude and phase response for input sinusoids of every frequency. While this basic idea may be practical for a real black box at a selected set of frequencies, it is hardly useful for filter design. Ideally, we wish to arrive at a mathematical formula for the frequency response of the filter given by Eq. (1.1). There are several ways of doing this. The first we consider is exactly analogous to the sine-wave analysis procedure given above.

Assuming Eq. (1.1) to be a linear time-invariant filter specification (which it is), let's take a few points in the frequency response by analytically ``plugging in'' sinusoids at a few different frequencies. Two graphs are required to fully represent the frequency response: the amplitude response (gain versus frequency) and phase response (phase shift versus frequency).

The frequency 0 Hz (often called dc, for direct current)

is always comparatively easy to handle when we analyze a filter. Since

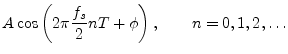

plugging in a sinusoid means setting

![]() ,

by setting

,

by setting ![]() , we obtain

, we obtain

![]() for all

for all ![]() . The input signal, then, is the same number

. The input signal, then, is the same number

![]() over and over again for each sample. It should be clear that

the filter output will be

over and over again for each sample. It should be clear that

the filter output will be

![]() for all

for all ![]() . Thus, the gain at frequency

. Thus, the gain at frequency ![]() is 2, which we get by dividing

is 2, which we get by dividing ![]() , the output amplitude, by

, the output amplitude, by

![]() , the input amplitude.

, the input amplitude.

Phase has no effect at ![]() Hz because it merely shifts a constant

function to the left or right. In cases such as this, where the phase

response may be arbitrarily defined, we choose a value which preserves

continuity. This means we must analyze at frequencies in a

neighborhood of the arbitrary point and take a limit. We will compute

the phase response at dc later, using different techniques. It is

worth noting, however, that at 0 Hz, the phase of every

real2.2 linear

time-invariant system is either 0 or

Hz because it merely shifts a constant

function to the left or right. In cases such as this, where the phase

response may be arbitrarily defined, we choose a value which preserves

continuity. This means we must analyze at frequencies in a

neighborhood of the arbitrary point and take a limit. We will compute

the phase response at dc later, using different techniques. It is

worth noting, however, that at 0 Hz, the phase of every

real2.2 linear

time-invariant system is either 0 or ![]() , with the phase

, with the phase ![]() corresponding to a sign change. The phase of a complex filter

at dc may of course take on any value in

corresponding to a sign change. The phase of a complex filter

at dc may of course take on any value in

![]() .

.

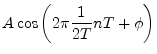

The next easiest frequency to look at is half the sampling rate,

![]() . In this case, using basic trigonometry (see §A.2), we can

simplify the input

. In this case, using basic trigonometry (see §A.2), we can

simplify the input ![]() as follows:

as follows:

|

|||

|

|||

| (2.2) |

| (2.3) |

If we back off a bit, the above results for the amplitude response are

obvious without any calculations. The filter

![]() is

equivalent (except for a factor of 2) to a simple two-point average,

is

equivalent (except for a factor of 2) to a simple two-point average,

![]() . Averaging adjacent samples in a signal

is intuitively a low-pass filter because at low frequencies the sample

amplitudes change slowly, so that the average of two neighboring

samples is very close to either sample, while at high frequencies the

adjacent samples tend to have opposite sign and to cancel out when

added. The two extremes are frequency 0 Hz, at which the averaging has

no effect, and half the sampling rate

. Averaging adjacent samples in a signal

is intuitively a low-pass filter because at low frequencies the sample

amplitudes change slowly, so that the average of two neighboring

samples is very close to either sample, while at high frequencies the

adjacent samples tend to have opposite sign and to cancel out when

added. The two extremes are frequency 0 Hz, at which the averaging has

no effect, and half the sampling rate ![]() where the samples

alternate in sign and exactly add to 0.

where the samples

alternate in sign and exactly add to 0.

We are beginning to see that Eq. (1.1) may be a low-pass filter

after all, since we found a boost of about 6 dB at the lowest

frequency and a null at the highest frequency. (A gain of 2 may be

expressed in decibels as

![]() dB, and a

null or notch is another

term for a gain of 0 at a single frequency.) Of course, we tried only

two out of an infinite number of possible frequencies.

dB, and a

null or notch is another

term for a gain of 0 at a single frequency.) Of course, we tried only

two out of an infinite number of possible frequencies.

Let's go for broke and plug the general sinusoid into Eq. (1.1),

confident that a table of trigonometry identities will see us through

(after all, this is the simplest filter there is, right?). To set the

input signal to a completely arbitrary sinusoid at amplitude ![]() ,

phase

,

phase ![]() , and frequency

, and frequency ![]() Hz, we let

Hz, we let

![]() . The output is then given by

. The output is then given by

All that remains is to reduce the above expression to a single sinusoid with some frequency-dependent amplitude and phase. We do this first by using standard trigonometric identities [2] in order to avoid introducing complex numbers. Next, a much ``easier'' derivation using complex numbers will be given.

Note that a sum of sinusoids at the same frequency, but possibly different phase and amplitude, can always be expressed as a single sinusoid at that frequency with some resultant phase and amplitude. While we find this result by direct derivation in working out our simple example, the general case is derived in §A.3 for completeness.

We have

| (2.4) |