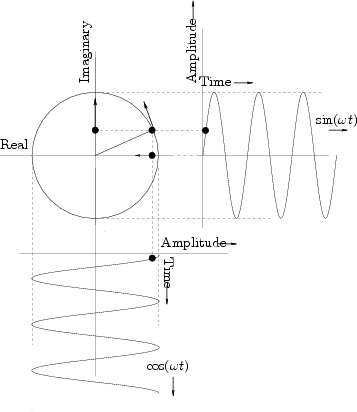

Figure 1.8 shows Euler's relation graphically as it applies to

sinusoids. A point traveling with uniform velocity around a circle

with radius 1 may be represented by

![]() in

the complex plane, where

in

the complex plane, where ![]() is time and

is time and ![]() is the number of

revolutions per second. The projection of this motion onto the

horizontal (real) axis is

is the number of

revolutions per second. The projection of this motion onto the

horizontal (real) axis is

![]() , and the projection onto

the vertical (imaginary) axis is

, and the projection onto

the vertical (imaginary) axis is

![]() . For

discrete-time circular motion, replace

. For

discrete-time circular motion, replace ![]() by

by ![]() to get

to get

![]() which may be interpreted as a

point which jumps an arc length

which may be interpreted as a

point which jumps an arc length

![]() radians along the circle

each sampling instant.

radians along the circle

each sampling instant.

|

For circular motion to ensue, the sinusoidal motions must be at the same frequency, one-quarter cycle out of phase, and perpendicular (orthogonal) to each other. (With phase differences other than one-quarter cycle, the motion is generally elliptical.)

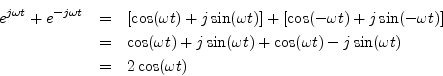

The converse of this is also illuminating. Take the usual circular

motion

![]() which spins counterclockwise along the unit

circle as

which spins counterclockwise along the unit

circle as ![]() increases, and add to it a similar but clockwise

circular motion

increases, and add to it a similar but clockwise

circular motion

![]() . This is shown in

Fig.1.9. Next apply Euler's identity to get

. This is shown in

Fig.1.9. Next apply Euler's identity to get

Thus,

This statement is a graphical or geometric interpretation of Eq. (1.11). A similar derivation (subtracting instead of adding) gives the sine identity Eq. (1.12).

We call

![]() a positive-frequency sinusoidal

component when

a positive-frequency sinusoidal

component when

![]() , and

, and

![]() is the

corresponding negative-frequency component. Note that both

sine and cosine signals have equal-amplitude positive- and

negative-frequency components (see also [83,53]). This

happens to be true of every real signal (i.e., non-complex). To

see this, recall that every signal can be represented as a sum of

complex sinusoids at various frequencies (its Fourier

expansion). For the signal to be real, every positive-frequency

complex sinusoid must be summed with a negative-frequency sinusoid of

equal amplitude. In other words, any counterclockwise circular motion

must be matched by an equal and opposite clockwise circular motion in

order that the imaginary parts always cancel to yield a real signal

(see Fig.1.9). Thus, a real signal always has a magnitude

spectrum which is symmetric about 0 Hz. Fourier symmetries such as

this are developed more completely in [83].

is the

corresponding negative-frequency component. Note that both

sine and cosine signals have equal-amplitude positive- and

negative-frequency components (see also [83,53]). This

happens to be true of every real signal (i.e., non-complex). To

see this, recall that every signal can be represented as a sum of

complex sinusoids at various frequencies (its Fourier

expansion). For the signal to be real, every positive-frequency

complex sinusoid must be summed with a negative-frequency sinusoid of

equal amplitude. In other words, any counterclockwise circular motion

must be matched by an equal and opposite clockwise circular motion in

order that the imaginary parts always cancel to yield a real signal

(see Fig.1.9). Thus, a real signal always has a magnitude

spectrum which is symmetric about 0 Hz. Fourier symmetries such as

this are developed more completely in [83].