Table of Contents

In this chapter, we will discuss not only the “what” of the OpenDocument format, but also the “why.” Thus, this chapter is as much evangelism as explanation.

Before we can talk about OpenDocument, we have to look at the current state of proprietary office suites and applications. In this world, all your documents are stored in a proprietary (often binary) format. As long as you stay within one particular office suite, this is not a problem. You can transfer data from one part of the suite to another; you can transfer text from the word processor to a presentation, or you can grab a set of numbers from the spreadsheet and convert it to a table in your word processing document.

The problems begin when you want to do a transfer that wasn’t intended by the authors of the office suite. Because the internal structure of the data is unknown to you, you can’t write a program that creates a new word processing document consisting of all the headings from a different document. If you need to do something that wasn’t provided by the software vendor, or if you must process the data with an application external to the office suite, you will have to convert that data to some neutral or “universal” format such as Rich Text Format (RTF) or comma-separated values (CSV) for import into the other applications. You have to rely on the kindness of strangers to include these conversions in the first place. Furthermore, some conversions can result in loss of formatting information that was stored with your data.

Note also that your data can become inaccessible when the software vendor moves to a new internal format and stops supporting your current version. (Some people actually suggest that this is not cause for complaint since, by putting your data into the vendor’s proprietary format, the vendor has now become a co-owner of your data. This is, and I mean this in the nicest possible way, a dangerously idiotic idea.)

The OpenDocument format has its roots in the XML format used to represent OpenOffice.org files. OpenOffice.org has as its mission “[t]o create, as a community, the leading international office suite that will run on all major platforms and provide access to all functionality and data through open-component based APIs and an XML-based file format.” OASIS has taken this format and is advancing its development

The OpenDocument file format is not simply an XML wrapper for a binary format, nor is it a one-to-one correspondence between the XML tags and the internal data structures of a specific piece of application software. Instead, it is an idealized representation of the document’s structure. This allows future versions of OpenOffice.org, or any other application that uses OpenDocument, to implement new features or completely alter internal data structures without requiring major changes to the file format. You can see the full details of this design decision at http://xml.openoffice.org/xml_advocacy.html

Although the XML file format is human-readable, it is fairly verbose. To save space, OpenDocument files are stored in JAR (Java Archive) format. A JAR file is a compressed ZIP file that has an additional “manifest” file that lists the contents of the archive. Since all JAR files are also ZIP files, you may use any ZIP file tool to unpack an OpenDocument file and read the XML directly.

File or Document?

Because a document in OpenDocument format can consist of several files, saying “an OpenDocument file” is not entirely accurate. However, saying “an OpenDocument document” sounds strange, and “a document in OpenDocument format” is verbose. For purposes of simplicity, when we refer to “an OpenDocument file,” we’re referring to the whole JAR file, with all its constituent files. When we need to refer to a particular file inside the JAR file, we’ll mention it by name.

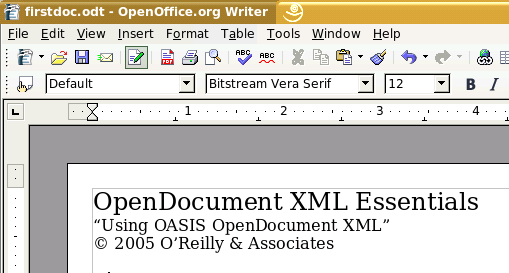

Figure 1.1, “Text Document” shows a short word processing document, which we have saved with the name firstdoc.odt.

Example 1.1, “Listing of Unzipped Text Document” shows the results of unzipping this file in Linux; the date, time, and CRC columns have been edited out to save horizontal space. The rows have been rearranged to assist in the explanation.

Example 1.1. Listing of Unzipped Text Document

[david@penguin ch01]$ unzip -v firstdoc.odt

Archive: firstdoc.odt

Length Method Size Ratio Name

-------- ------ ------- ----- ----

39 Stored 39 0% mimetype

3441 Defl:N 885 74% content.xml

6748 Defl:N 1543 77% styles.xml

1173 Stored 1173 0% meta.xml

642 Defl:N 345 46% Thumbnails/thumbnail.png

7176 Defl:N 1307 82% settings.xml

1074 Defl:N 308 71% META-INF/manifest.xml

0 Stored 0 0% Configurations2/

0 Stored 0 0% Pictures/

-------- ------- --- -------

20293 5600 72% 9 files

These files are, in order:

- mimetype

This file has a single line of text which gives the MIME type for the document.The various MIME types are summarized in Table 1.1, “MIME Types and Extensions for OpenDocument Documents”.

- content.xml

The actual content of the document

- styles.xml

This file contains information about the styles used in the content. The content and style information are in different files on purpose; separating content from presentation provides more flexibility.

- meta.xml

Meta-information about the content of the document (such things as author, last revision date, etc.) This is different from the META-INF directory.

- settings.xml

This file contains information that is specific to the application. Some of this information, such as window size/position and printer settings is common to most documents. A text document would have information such as zoom factor, whether headers and footers are visible, etc. A spreadsheet would contain information about whether column headers are visible, whether cells with a value of zero should show the zero or be empty, etc.

- META-INF/manifest.xml

This file gives a list of all the other files in the JAR. This is meta-information about the entire JAR file. It is not not the same as the manifest file used in the Java language. This file must be in the JAR file if you want OpenOffice.org to be able to read it.

- Configurations2

I’m not sure what this directory contains!

- Pictures

This directory will contain the list of all images contained in the document. Some applications may create this directory in the JAR file even if there aren’t any images in the file.

Table 1.1. MIME Types and Extensions for OpenDocument Documents

| Document Type | MIME Type | Document Extension |

|---|---|---|

Text document | application/vnd.oasis.opendocument.text | odt |

Text document used as template | application/vnd.oasis.opendocument.text-template | ott |

Graphics document (Drawing) | application/vnd.oasis.opendocument.graphics | odg |

Drawing document used as template | application/vnd.oasis.opendocument.graphics-template | otg |

Presentation document | application/vnd.oasis.opendocument.presentation | odp |

Presentation document used as template | application/vnd.oasis.opendocument.presentation-template | otp |

Spreadsheet document | application/vnd.oasis.opendocument.spreadsheet | ods |

Spreadsheet document used as template | application/vnd.oasis.opendocument.spreadsheet-template | ots |

Chart document | application/vnd.oasis.opendocument.chart | odc |

Chart document used as template | application/vnd.oasis.opendocument.chart-template | otc |

Image document | application/vnd.oasis.opendocument.image | odi |

Image document used as template | application/vnd.oasis.opendocument.image-template | oti |

Formula document | application/vnd.oasis.opendocument.formula | odf |

Formula document used as template | application/vnd.oasis.opendocument.formula-template | otf |

Global Text document | application/vnd.oasis.opendocument.text-master | odm |

Text document used as template for HTML documents | application/vnd.oasis.opendocument.text-web | oth |

We will discuss the meta.xml, settings.xml, and style.xml files in greater detail in the next chapter, and the remainder of the book will cover the various flavors of the content.xml file.

First, let’s look at the contents of manifest.xml, most of which is self-explanatory.

<?xml version="1.0" encoding="UTF-8"?> <!DOCTYPE manifest:manifest PUBLIC "-//OpenOffice.org//DTD Manifest 1.0//EN" "Manifest.dtd"> <manifest:manifest xmlns:manifest="urn:oasis:names:tc:opendocument:xmlns:manifest:1.0"> <manifest:file-entry manifest:media-type="application/vnd.oasis.opendocument.text" manifest:full-path="/"/> <manifest:file-entry manifest:media-type="application/vnd.sun.xml.ui.configuration" manifest:full-path="Configurations2/"/> <manifest:file-entry manifest:media-type="" manifest:full-path="Pictures/"/> <manifest:file-entry manifest:media-type="text/xml" manifest:full-path="content.xml"/> <manifest:file-entry manifest:media-type="text/xml" manifest:full-path="styles.xml"/> <manifest:file-entry manifest:media-type="text/xml" manifest:full-path="meta.xml"/> <manifest:file-entry manifest:media-type="" manifest:full-path="Thumbnails/thumbnail.png"/> <manifest:file-entry manifest:media-type="" manifest:full-path="Thumbnails/"/> <manifest:file-entry manifest:media-type="text/xml" manifest:full-path="settings.xml"/> </manifest:manifest>

The manifest:media-type for the root directory tells what kind of file this is. Its content is the same as the content of the mimetype file, as shown in Table 1.1, “MIME Types and Extensions for OpenDocument Documents”, adapted from the OpenDocument specification.

There is an entry for a Pictures directory, even though there are no images in the file. If there were an image, the unzipped file would contain a Pictures directory, and the relevant portion of the manifest would now look like this:

<manifest:file-entry manifest:media-type="image/png"

manifest:full-path="Pictures/100002000000002000000020DF8717E9.png" />

<manifest:file-entry manifest:media-type=""

manifest:full-path="Pictures/" />

If you are using OpenOffice.org and have included OpenOffice.org BASIC scripts, your packed file will include a Basic directory, and the manifest will describe it and its contents.

If you are building your own document with embedded objects (charts, pictures, etc.) you must keep track of them in the manifest file, or OpenOffice.org will not be able to find them.

The manifest.xml used the manifest namespace for all of its element and attribute names. OpenDocument uses a large number of namespace declarations in the root element of the content.xml, styles.xml, and settings.xml files. Table 1.2, “Namespaces for OpenDocument”, which is adapted from the OpenDocument specification, shows the most important of these.

Table 1.2. Namespaces for OpenDocument

| Namespace Prefix | Describes | Namespace URI |

|---|---|---|

office | Common information not contained in another, more specific namespace. | urn:oasis:names:tc:opendocument:xmlns:office:1.0 |

meta | Meta information | urn:oasis:names:tc:opendocument:xmlns:meta:1.0 |

config | Application-specific settings. | urn:oasis:names:tc:opendocument:xmlns:config:1.0 |

text | Text documents and text parts of other document types (e.g., a spreadsheet cell). | urn:oasis:names:tc:opendocument:xmlns:text:1.0 |

table | Content of spreadsheets or tables in a text document. | urn:oasis:names:tc:opendocument:xmlns:table:1.0 |

drawing | Graphic content. | urn:oasis:names:tc:opendocument:xmlns:drawing:1.0 |

presentation | Presentation content. | urn:oasis:names:tc:opendocument:xmlns:presentation:1.0 |

dr3d | 3D graphic content. | urn:oasis:names:tc:opendocument:xmlns:dr3d:1.0 |

anim | Animation content. | urn:oasis:names:tc:opendocument:xmlns:animation:1.0 |

chart | Chart content. | urn:oasis:names:tc:opendocument:xmlns:chart:1.0 |

form | Forms and controls. | urn:oasis:names:tc:opendocument:xmlns:form:1.0 |

script | Scripts or events. | urn:oasis:names:tc:opendocument:xmlns:script:1.0 |

style | Style and inheritance model used by OpenDocument; also common formatting attributes. | urn:oasis:names:tc:opendocument:xmlns:style:1.0 |

number | Data style information. | urn:oasis:names:tc:opendocument:xmlns:data style:1.0 |

manifest | The package manifest. | urn:oasis:names:tc:opendocument:xmlns:manifest:1.0 |

fo | Attributes defined in XSL:FO. | urn:oasis:names:tc:opendocument:xmlns:xsl-fo-compatible:1.0 |

svg | Elements or attributes defined in SVG. | urn:oasis:names:tc:opendocument:xmlns:svg-compatible:1.0 |

smil | Attributes defined in SMIL20. | urn:oasis:names:tc:opendocument:xmlns:smil-compatible:1.0 |

dc | The Dublin Core Namespace. | http://purl.org/dc/elements/1.1/ |

xlink | The XLink namespace. | http://www.w3.org/1999/xlink |

math | MathML Namespace | http://www.w3.org/1998/Math/MathML |

xforms | The XForms namespace. | http://www.w3.org/2002/xforms |

xforms | The WWW Document Object Model namespace. | http://www.w3.org/2001/xml-events |

ooo | The OpenOffice.org namespace. | http://openoffice.org/2004/office |

ooow | The OpenOffice.org writer namespace. | http://openoffice.org/2004/writer |

ooo | The OpenOffice.org spreadsheet (calc) namespace. | http://openoffice.org/2004/calc |

Whenever possible, OpenDocument uses existing standards for namespaces. The text namespace adds elements and attributes that describe the aspects of word processing that the fo namespace lacks; similarly draw and dr3d add functionality that is not already found in svg.

If you unzip an OpenDocument file, it will unzip into the current directory. If you unpack a second document, your unzip program will either overwrite the old files or prompt you at each file. This is inconvenient, so we have written a Perl program, shown in Example 1.2, “Program to Unpack an OpenOffice.org Document”, which will unpack an OpenDocument file whose name has the form filename.extension. It will unzip the files into a directory named filename_extension. You will find this program as file odunpack.pl in directory ch01 in the downloadable example files.

Example 1.2. Program to Unpack an OpenOffice.org Document

#!/usr/bin/perl

#

# Unpack an OpenDocument file to a directory.

#

# Archive::Zip is used to unzip files.

# File::Path is used to create and remove directories.

#

use Archive::Zip;

use File::Path;

use strict;

my $file_name;

my $dir_name;

my $suffix;

my $zip;

my $member_name;

my @member_list;

if (scalar @ARGV != 1)

{

print "Usage: $0 filename\n";

exit;

}

$file_name = $ARGV[0];

#

# Only allow filenames that have valid OpenDocument extensions

#

if ($file_name =~ m/\.(o[dt][tgpscif]|odm|oth)/)

{

$suffix = $1;

#

# Create directory name based on filename

#

($dir_name = $file_name) =~ s/\.$suffix//;

$dir_name .= "_$suffix";

#

# Forcibly remove old directory, re-create it,

# and unzip the OpenOffice.org file into that directory

#

rmtree($dir_name, 0, 0);

mkpath($dir_name, 0, 0755);

$zip = Archive::Zip->new( $file_name );

@member_list = $zip->memberNames( );

foreach $member_name (@member_list)

{

$zip->extractMember( $member_name, "$dir_name/$member_name" );

}

print "$file_name unpacked.\n";

}

else

{

print "This does not appear to be an OpenDocument file.\n";

print "Legal suffixes are .odt, .ott, .odg, .otg, .odp, .otp,\n";

print ".ods, .ots, .odc, .otc, .odi, .oti, .odf, .otf, .odm, and .oth\n";

}

When you look at the unpacked files in a text editor, you will notice that most of them consist of only two lines: a <!DOCTYPE> declaration followed by a single line containing the rest of the document. Ordinarily this is no problem, as the documents are meant to be read by a program rather than a human. In order to analyze the XML files for this book, we had to put the files in a more readable format. In OpenOffice.org, this was easily accomplished by turning off the “Size optimization for XML format (no pretty printing)” checkbox in the Options—Load/Save—General dialog box. All the files we created from that point onward were nicely formatted. If you are receiving files from someone else, and you do not wish to go to the trouble of opening and re-saving each of them, you may use XSLT to do the indenting, as explained in the section called “Using XSLT to Indent OpenDocument Files”.

If you need to pack (or repack) files to produce a single OpenDocument file, Example 1.3, “Program to Pack Files to Create an OpenDocument File” does exactly that. It takes the files in a directory of the form filename_extension and creates a document named filename.extension (or any other name you wish to give as a second argument on the command line). You will find this program as file odpack.pl in directory ch01 in the downloadable example files.

Example 1.3. Program to Pack Files to Create an OpenDocument File

#!/usr/bin/perl

#

# Repack a directory to an OpenDocument file

#

# Directory xyz_odt will be packed into xyz.odt, etc.

#

#

use Archive::Zip; # to zip files

use Cwd; # to get current working directory

use strict;

my $dir_name; # directory name to zip

my $file_name = ""; # destination file name

my $suffix; # file extension

my $current_dir; # current directory

my $zip; # a zip file object

if (scalar @ARGV < 1 || scalar @ARGV > 2)

{

print "Usage: $0 directoryname [newfilename]\n";

exit;

}

$dir_name = $ARGV[0];

#

# If no new filename is given, create a filename

# based on directory name

#

if ($ARGV[1])

{

$file_name = $ARGV[1];

}

else

{

if ($dir_name =~ m/_(o[dt][tgpscif]|odm|oth)/)

{

$suffix = $1;

($file_name = $dir_name) =~ s/(_$suffix)//;

$file_name .= ".$suffix";

}

else

{

print "This does not appear to be an unpacked OpenDocument file.\n";

print "Legal suffixes are _odt, _ott, _odg, _otg, _odp, _otp, _ods,\n";

print "_ots, _odc, _otc, _odi, _oti, _odf, _otf, _odm, and _oth\n";

$file_name = "";

}

}

if ($file_name ne "")

{

$zip = Archive::Zip->new();

$current_dir = cwd();

if (chdir($dir_name))

{

$zip->addTree( '.' );

$zip->writeToFileNamed( "../$file_name" );

print "$dir_name packed to $file_name.\n";

chdir($current_dir);

}

else

{

print "Could not change directory to $dir_name\n";

}

}As you begin to work with OpenDocument files, you may want to write a program that constructs a document with some feature that isn’t explained in this book—this is, after all, an “essentials” book. Just start OpenOffice.org or KOffice, create a document that has the feature you want, unpack the file, and look for the XML that implements it. To get a better understanding of how things works, change the XML, repack the document, and reload it. Once you know how a feature works, don’t hesitate to copy and paste the XML from the OpenDocument file into your program. In other words, cheat. It worked for me when I was writing this book, and it can work for you too!