Chapter 3. Advanced Styling

| If you know HTML, CSS, and JavaScript, you already have the tools you need to develop Android applications. This hands-on book shows you how to use these open source web standards to design and build apps that can be adapted for any Android device -- without having to use Java. Buy the print book or ebook or purchase it in iBooks. |

In our quest to build an Android app without Java, we’ve so far learned how to use CSS to style a collection of HTML pages to look like an Android app. In this chapter, we’ll lay the groundwork to make those same pages behave like an Android app. Specifically, we’ll discuss:

Using Ajax to turn a full website into a single page app.

Creating a back button with history using JavaScript.

Saving the app as an icon on the homescreen.

Adding a Touch of Ajax

The term Ajax (Asynchronous JavaScript and XML) has become such a buzzword that I’m not even sure I know what it means anymore. For the purposes of this book, I’m going to use Ajax to refer to the technique of using JavaScript to send requests to a web server without reloading the current page (e.g. to retrieve some HTML, submit a form, etc.). This approach makes for a very smooth user experience, but does require that you reinvent a lot of wheels.

For example, if you are loading external pages dynamically, the browser will not give any indication of progress or errors to the users. Furthermore, the back button will not work as expected unless you take pains to support it. In other words, you have to do a lot of work to make a sweet Ajax app. That said, the extra effort can really pay off because Ajax allows you to create a much richer user experience.

Traffic Cop

For my next series of examples, I’m going to write a single page called android.html that will sit in front of all of the site’s other pages. Here’s how it works:

On first load,

android.htmlwill present the user with a nicely formatted version of the site navigation.I’ll then use jQuery to “hijack” the

onclickactions of thenavlinks so that when the user clicks on a link, the browser page will not navigate to the target link. Rather, jQuery will load a portion of the HTML from the remote page and deliver the data to the user by updating the current page.

I’ll start with the most basic functional version of the code and improve it as we go along.

The HTML for the android.html wrapper page is extremely simple (see Example 3.1, “This simple HTML wrapper markup will sit in front of the rest of the site's pages.”). In the head section, I set the title and viewport options, and include links to a stylesheet (android.css) and two JavaScript files: jquery.js and a custom JavaScript file named android.js.

Note

You must put a copy of jquery.js in the same directory as the HTML file. For more information on where to get jquery.js and what to do with it, see the section called “Intro to JavaScript”. You should do this now before proceeding further.

The body just has two div containers: a header with the initial title in an h1 tag, and an empty div container, which will end up holding HTML snippets retrieved from other pages.

Example 3.1. This simple HTML wrapper markup will sit in front of the rest of the site's pages.

<html>

<head>

<title>Jonathan Stark</title>

<meta name="viewport" content="user-scalable=no, width=device-width" />

<link rel="stylesheet" href="android.css" type="text/css" media="screen" />

<script type="text/javascript" src="jquery.js"></script>

<script type="text/javascript" src="android.js"></script>

</head>

<body>

<div id="header"><h1>Jonathan Stark</h1></div>

<div id="container"></div>

</body>

</html>

Moving on to the android.css CSS file, you can see in Example 3.2, “The base CSS for the page is just a slightly reshuffled version of previous examples.” that I’ve reshuffled some of the properties from previous examples in Chapter 2, Basic Styling (e.g. some of the #header h1 properties have been moved up to #header), but overall everything should look familiar (if not, please review Chapter 2, Basic Styling).

Example 3.2. The base CSS for the page is just a slightly reshuffled version of previous examples.

body {

background-color: #ddd;

color: #222;

font-family: Helvetica;

font-size: 14px;

margin: 0;

padding: 0;

}

#header {

background-color: #ccc;

background-image: -webkit-gradient(linear, left top, left bottom, from(#ccc), to(#999));

border-color: #666;

border-style: solid;

border-width: 0 0 1px 0;

}

#header h1 {

color: #222;

font-size: 20px;

font-weight: bold;

margin: 0 auto;

padding: 10px 0;

text-align: center;

text-shadow: 0px 1px 1px #fff;

}

ul {

list-style: none;

margin: 10px;

padding: 0;

}

ul li a {

background-color: #FFF;

border: 1px solid #999;

color: #222;

display: block;

font-size: 17px;

font-weight: bold;

margin-bottom: -1px;

padding: 12px 10px;

text-decoration: none;

}

ul li:first-child a {

-webkit-border-top-left-radius: 8px;

-webkit-border-top-right-radius: 8px;

}

ul li:last-child a {

-webkit-border-bottom-left-radius: 8px;

-webkit-border-bottom-right-radius: 8px;

}

ul li a:active,ul li a:hover {

background-color:blue;

color:white;

}

#content {

padding: 10px;

text-shadow: 0px 1px 1px #fff;

}

#content a {

color: blue;

}

Setting up Some Content to Work With

This JavaScript loads a document called index.html, and will not work without it. Before you proceed, copy the HTML file from Example 2.1, “The HTML document we’ll be styling.” into the same directory as android.html, and be sure to name it index.html. However, none of the links in it will work unless the targets of the links actually exist. You can create these files yourself or download the example code from the book's web site (see the section called “How to Contact Us”).

To give you a couple functioning links to play with, you can create about.html, blog.html, and consulting-clinic.html. To do so, just duplicate index.html a few times and change the filename of each copy to match the related link. For added effect, you can change the content of the <h2> tag in each file to match the filename. For example, the h2 in blog.html would be <h2>Blog</h2>.

At this point, you should have the following files in your working directory:

android.htmlYou created this in Example 3.1, “This simple HTML wrapper markup will sit in front of the rest of the site's pages.”.

android.cssYou created this in Example 3.2, “The base CSS for the page is just a slightly reshuffled version of previous examples.”.

index.htmlA copy of the HTML file in Example 2.1, “The HTML document we’ll be styling.”.

about.htmlA copy of

index.html, with the<h2>set to "About".blog.htmlA copy of

index.html, with the<h2>set to "Blog".consulting-clinic.htmlA copy of

index.html, with the<h2>set to "Consulting Clinic".

Routing Requests with JavaScript

The JavaScript in android.js is where all the magic happens in this example. Create this file in the same directory as your android.html file. Please refer to Example 3.3, “This bit of JavaScript in android.js converts the links on the page to Ajax requests.” as I go through it line by line.

Example 3.3. This bit of JavaScript in android.js converts the links on the page to Ajax requests.

$(document).ready(function(){  loadPage();

});

function loadPage(url) {

loadPage();

});

function loadPage(url) { if (url == undefined) {

$('#container').load('index.html #header ul', hijackLinks);

if (url == undefined) {

$('#container').load('index.html #header ul', hijackLinks); } else {

$('#container').load(url + ' #content', hijackLinks);

} else {

$('#container').load(url + ' #content', hijackLinks); }

}

function hijackLinks() {

}

}

function hijackLinks() { $('#container a').click(function(e){

$('#container a').click(function(e){ e.preventDefault();

e.preventDefault(); loadPage(e.target.href);

loadPage(e.target.href); });

}

});

}

Here I’m using jQuery’s document ready function to have the browser run the | |

The | |

If a value is not sent into the function (as will be the case when it is called for the first time from the document ready function), Note

| |

This line is executed if the url parameter has a value. It says, in effect: “Get the | |

Once the | |

On this line, | |

Normally, a web browser will navigate to a new page when a link is clicked. This navigation response is called the “default behavior” of the link. Since we are handling clicks and loading pages through JavaScript, we need to prevent this default behavior. On this line, which (along with the next line) is triggered when a user clicks one of the links, I’ve done so by calling the built-in | |

When the user clicks, I pass the url of the remote page to the |

Tip

One of my favorite things about JavaScript is that you can pass a function as a parameter to another function. Although this looks weird at first, it’s extremely powerful and allows you to make your code modular and reusable. If you’d like to learn more, you should check out “JavaScript: The Good Parts” by Douglas Crockford. In fact, if you are working with JavaScript, you should check out everything by Douglas Crockford; you’ll be glad you did.

Click handlers do not run when the page first loads; they run when the user actually clicks a link. Assigning click handlers is like setting booby traps; you do some initial setup work for something that may or may not be triggered later.

Tip

It’s worth taking a few minutes to read up on the properties of the event object that JavaScript creates in response to user actions in the browser. A good reference is located at http://www.w3schools.com/htmldom/dom_obj_event.asp.

Caution

When testing the code in this chapter, be sure you point your browser at the android.html page. Web servers will typically default to displaying index.html if you just navigate to the directory that the files are in. Normally this is helpful, but in this case it will cause a problem.

Simple Bells and Whistles

With this tiny bit of HTML, CSS, and JavaScript, we have essentially turned an entire website into a single page application. However, it does still leave quite a bit to be desired. Let’s slick things up a bit.

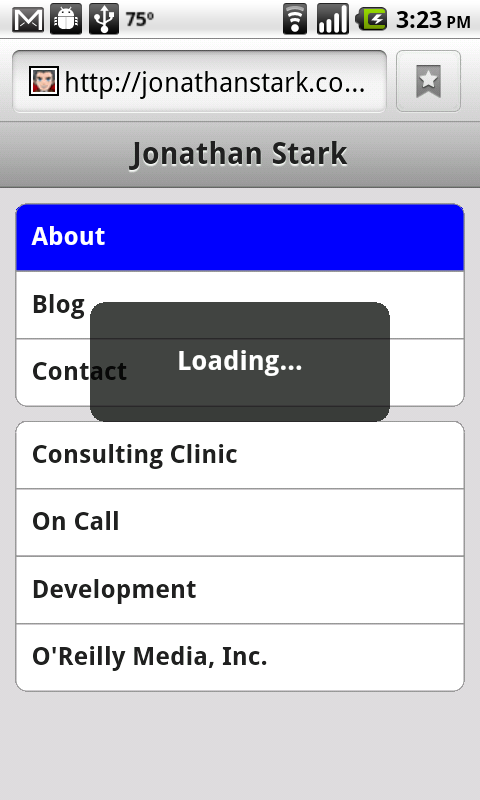

Progress Indicator

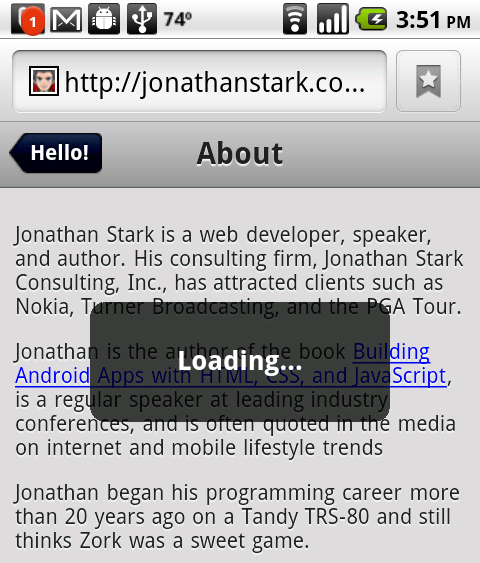

Since we are not allowing the browser to navigate from page to page, the user will not see any indication of progress while data is loading. We need to provide some feedback to the user to let them know that something is, in fact, happening. Without this feedback, the user will wonder if they actually clicked the link or missed it, and will often start clicking all over the place in frustration. This can lead to increased server load and application instability (i.e. crashing).

Thanks to jQuery, providing a progress indicator only takes two lines of code. We’ll just append a loading div to the body when loadPage() starts, and remove the loading div when hijackLinks() is done. Example 3.4, “Adding a simple progress indicator to the page.” shows a modified version of Example 3.3, “This bit of JavaScript in android.js converts the links on the page to Ajax requests.”. The lines you need to add to android.js are shown in bold.

Example 3.4. Adding a simple progress indicator to the page.

$(document).ready(function(){

loadPage();

});

function loadPage(url) {

$('body').append('<div id="progress">Loading...</div>');

if (url == undefined) {

$('#container').load('index.html #header ul', hijackLinks);

} else {

$('#container').load(url + ' #content', hijackLinks);

}

}

function hijackLinks() {

$('#container a').click(function(e){

e.preventDefault();

loadPage(e.target.href);

});

$('#progress').remove();

}

See Example 3.5, “CSS added to android.css used to style the progress indicator.” for the CSS that needs to be added to android.css to style the progress div.

Example 3.5. CSS added to android.css used to style the progress indicator.

#progress {

-webkit-border-radius: 10px;

background-color: rgba(0,0,0,.7);

color: white;

font-size: 18px;

font-weight: bold;

height: 80px;

left: 60px;

line-height: 80px;

margin: 0 auto;

position: absolute;

text-align: center;

top: 120px;

width: 200px;

}

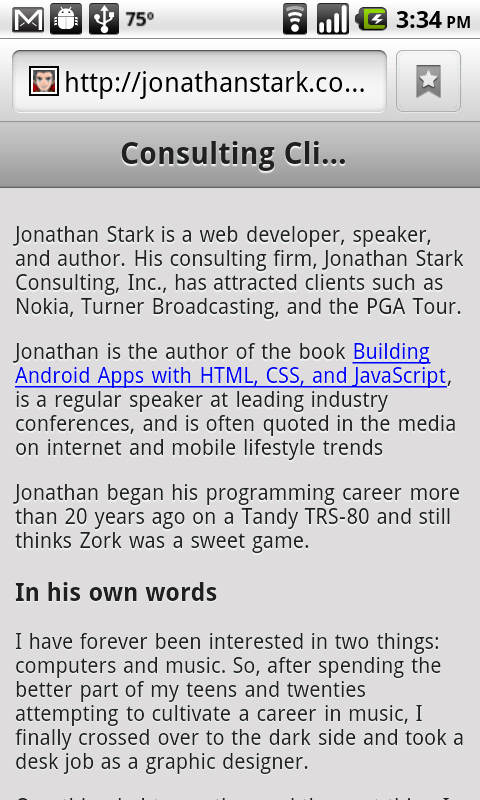

Figure 3.1. Without a progress indicator of some kind, your app will seem unresponsive and your users will get frustrated.

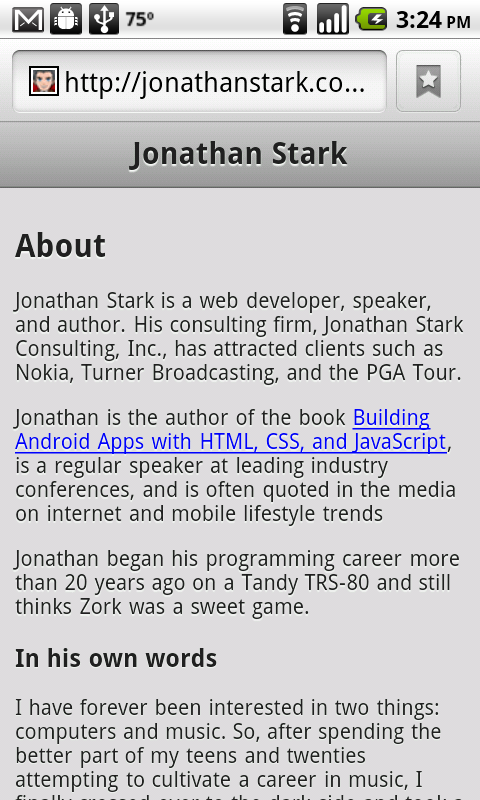

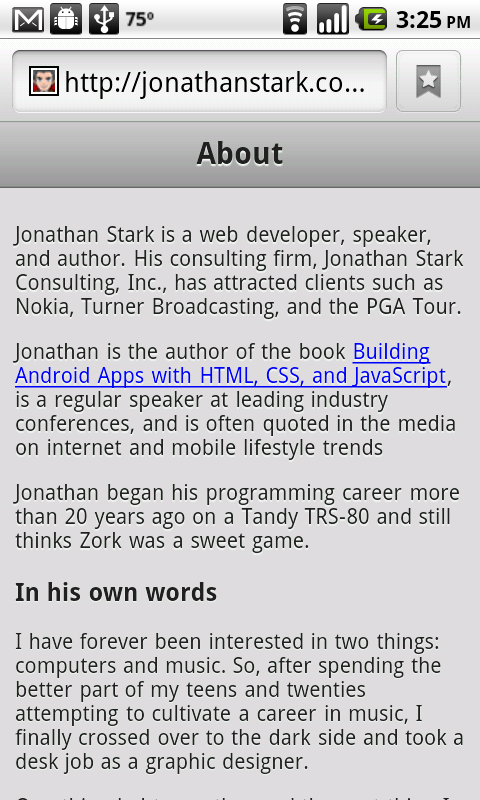

Setting the Page Title

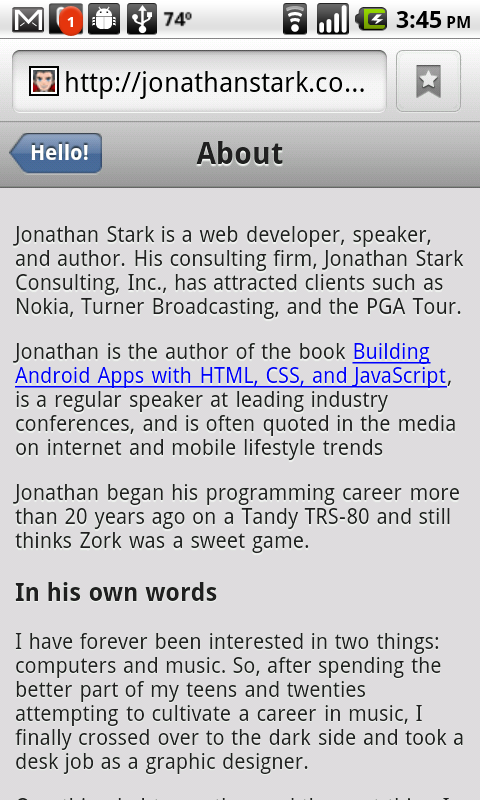

My site happens to have a single h2 at the beginning of each page that would make a nice page title (see Figure 3.2, “Before moving the page heading to the toolbar...”). You can see this in the HTML source shown in Chapter 2, Basic Styling. To be more mobile friendly, I’m going to pull that title out of the content and put it in the header (see Figure 3.3, “...and after moving the page heading to the toolbar.”). Again, jQuery to the rescue: you can just add three lines to the hijackLinks() function to make it happen. Example 3.6, “Using the h2 from the target page as the toolbar title.” shows the hijackLinks function with these changes.

Example 3.6. Using the h2 from the target page as the toolbar title.

function hijackLinks() {

$('#container a').click(function(e){

e.preventDefault();

loadPage(e.target.href);

});

var title = $('h2').html() || 'Hello!';

$('h1').html(title);

$('h2').remove();

$('#progress').remove();

}

Note

Note that I added the title lines before the line that removes the progress indicator. I like to remove the progress indicator as the very last action because I think it makes the application feel more responsive.

The double pipe (||) in the first line of inserted code (shown in bold) is the JavaScript logical operator OR. Translated into English, that line would read: “Set the title variable to the HTML contents of the h2 element, or to the string ‘Hello!’ if there is no h2 element.” This is important because the first page load won’t contain an h2 because we are just grabbing the nav uls.

Note

This point probably needs some clarification. When the user first loads the android.html url, they are only going to see the overall site navigation elements, as opposed to any site content. They won't see any site content until they tap a link on this initial navigation page.

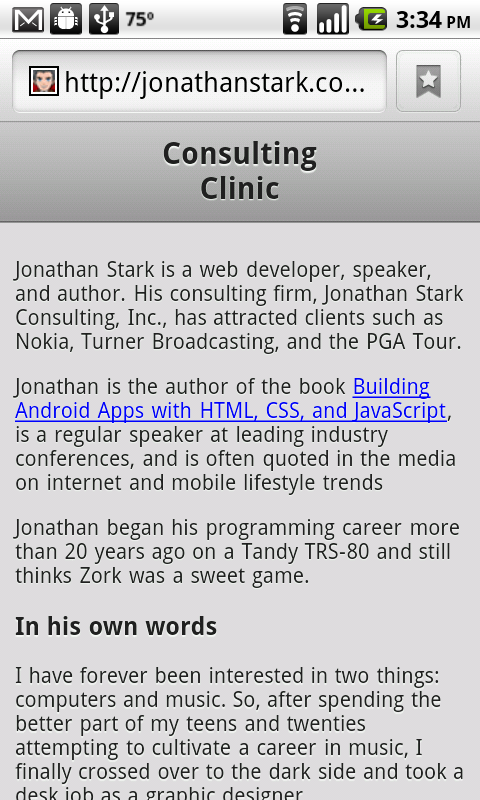

Handling Long Titles

Suppose I had a page on my site with a title too long to fit in the header bar (Figure 3.4, “Text wrapping in the toolbar is not very attractive...”). I could just let the text break onto more than one line, but that would not be very attractive. Rather, I can update the #header h1 styles such that long text will be truncated with a trailing ellipis (see Figure 3.5, “...but we can beautify it with a CSS ellipsis.” and Example 3.7, “Adding an ellipsis to text that is too long for its container.”). This might be my favorite little-known CSS trick.

Example 3.7. Adding an ellipsis to text that is too long for its container.

#header h1 {

color: #222;

font-size: 20px;

font-weight: bold;

margin: 0 auto;

padding: 10px 0;

text-align: center;

text-shadow: 0px 1px 1px #fff;

max-width: 160px;

overflow: hidden;

white-space: nowrap;

text-overflow: ellipsis;

}

Here’s the rundown: max-width: 160px instructs the browser not to allow the h1 element to grow wider than 160px. Then, overflow: hidden instructs the browser to chop off any content that extends outside of the element borders. Next, white-space: nowrap prevents the browser from breaking the line into two. Without this line, the h1 would just get taller to accommodate the text at the defined width. Finally, text-overflow: ellipsis appends three dots to the end of any chopped off text to indicate to the user that she is not seeing the entire string.

Automatic Scroll-to-Top

Let’s say you have a page that is longer than the viewable area on the phone. The user visits the page, scrolls down to the bottom, and clicks on a link to an even longer page. In this case, the new page will show up "pre-scrolled" instead of at the top as you'd expect.

Technically, this makes sense because we are not actually leaving the current (scrolled) page, but it’s certainly a confusing situation for the user. To rectify the situation, I have added a scrollTo() command to the loadPage() function (see Example 3.8, “It’s a good idea to scroll back to the top when a user navigates to a new page.”).

Whenever a user clicks a link, the page will first jump to the top. This has the added benefit of ensuring that the loading graphic is visible if the user clicks a link at the bottom of a long page.

Example 3.8. It’s a good idea to scroll back to the top when a user navigates to a new page.

function loadPage(url) {

$('body').append('<div id="progress">Loading...</div>');

scrollTo(0,0);

if (url == undefined) {

$('#container').load('index.html #header ul', hijackLinks);

} else {

$('#container').load(url + ' #content', hijackLinks);

}

}

Hijacking Local Links Only

Like most sites, mine has links to external pages (i.e. pages hosted on other domains). I don’t want to hijack these external links because it wouldn’t make sense to inject their HTML into my Android-specific layout. In Example 3.9, “You can allow external pages to load normally by checking the domain name of the url.”, I have added a conditional that checks the url for the existence of my domain name. If it’s found, the link is hijacked and the content is loaded into the current page; i.e. Ajax is in effect. If not, the browser will navigate to the url normally.

Caution

You must change jonathanstark.com to the appropriate domain or host name for your web site, or the links to pages on your web site will no longer be hijacked.

Example 3.9. You can allow external pages to load normally by checking the domain name of the url.

function hijackLinks() {

$('#container a').click(function(e){

var url = e.target.href;

if (url.match(/jonathanstark.com/)) {

e.preventDefault();

loadPage(url);

}

});

var title = $('h2').html() || 'Hello!';

$('h1').html(title);

$('h2').remove();

$('#progress').remove();

}

Tip

The url.match function uses a language, regular expressions, that is often embedded within other programming languages such as JavaScript, PHP, and Perl. Although this regular expression is simple, more complex expressions can be a bit intimidating, but are well worth becoming familiar with. My favorite regex page is located at http://www.regular-expressions.info/javascriptexample.html.

Roll Your Own Back Button

The elephant in the room at this point is that the user has no way to navigate back to previous pages (remember that we've hijacked all the links, so the browser page history won’t work). Let’s address that by adding a back button to the top left corner of the screen. First, I’ll update the JavaScript, and then I’ll do the CSS.

Adding a standard toolbar back button to the app means keeping track of the user’s click history. To do this, we’ll have to A) store the url of the previous page so we know where to go back to, and B) store the title of the previous page, so we know what label to put on the back button.

Adding this feature touches on most of the JavaScript we’ve written so far in this chapter, so I’ll go over the entire new version of android.js line by line (see Example 3.10, “Expanding the existing JavaScript example to include support for a back button.”). The result will look like Figure 3.6, “It wouldn’t be an mobile app without a glossy, left-arrow back button.”.

Example 3.10. Expanding the existing JavaScript example to include support for a back button.

var hist = [];var startUrl = 'index.html';

$(document).ready(function(){

loadPage(startUrl); }); function loadPage(url) { $('body').append('<div id="progress">Loading...</div>');

scrollTo(0,0); if (url == startUrl) {

var element = ' #header ul'; } else { var element = ' #content'; } $('#container').load(url + element, function(){

var title = $('h2').html() || 'Hello!'; $('h1').html(title); $('h2').remove(); $('.leftButton').remove();

hist.unshift({'url':url, 'title':title});

if (hist.length > 1) {

$('#header').append('<div class="leftButton">'+hist[1].title+'</div>');

$('#header .leftButton').click(function(){

var thisPage = hist.shift();

var previousPage = hist.shift(); loadPage(previousPage.url); }); } $('#container a').click(function(e){

var url = e.target.href; if (url.match(/jonathanstark.com/)) {

e.preventDefault(); loadPage(url); } }); $('#progress').remove(); }); }

On this line, I’m initializing a variable named | |

Here I’m defining the relative url of the remote page to load when the user first visits | |

This line and the next make up the document ready function definition. Note that unlike previous examples, I’m passing the start page to the | |

On to the | |

This if...else statement determines which elements to load from the remote page. For example, if we want the start page, we grab the | |

On this line, the url parameter and the appropriate source element are concatenated as the first parameter passed to the load function. As for the second parameter, I’m passing an anonymous function (an unnamed function that is defined inline) directly. As we go through the anonymous function, you’ll notice a strong resemblance to the | |

On this line, I’m removing the | |

Here I’m using the built-in | |

On this line, I’m using the built-in | |

Next, I’m adding that | |

In this block of code, I’m binding an anonymous function to the click handler of the back button. Remember, click handler code executes when the user clicks, not when the page loads. So, after the page loads and the user clicks to go back, the code inside this function will run. | |

This line and the next use the built-in | |

The remaining lines were copied exactly from previous examples, so I won’t rehash them here. | |

This is the URL matching code introduced earlier in this chapter. Remember to replace |

Tip

Please visit http://www.hunlock.com/blogs/Mastering_Javascript_Arrays for a full listing of JavaScript array functions with descriptions and examples.

Now that we have our back button, all that remains is to purty it up with some CSS (see Example 3.11, “Add the following to android.css to beautify the back button with a border image.”). I start off by styling the text with font-weight, text-align, line-height, color, and text-shadow. I continue by placing the div precisely where I want it on the page with position, top, and left. Then, I make sure that long text on the button label will truncate with an ellipis using max-width, white-space, overflow, and text-overflow. Finally, I apply a graphic with border-width and -webkit-border-image. Unlike my earlier border image example, this image has a different width for the left and right borders because the image is made asymetrical by the arrowhead on the left side.

Note

Don't forget that you'll need an image for this button. You'll need to save it as back_button.png in the images folder underneath the folder that holds your HTML file. See the section called “Adding Basic Behavior with jQuery” for tips on finding or creating your own button images.

Example 3.11. Add the following to android.css to beautify the back button with a border image.

#header div.leftButton {

font-weight: bold;

text-align: center;

line-height: 28px;

color: white;

text-shadow: 0px -1px 1px rgba(0,0,0,0.6);

position: absolute;

top: 7px;

left: 6px;

max-width: 50px;

white-space: nowrap;

overflow: hidden;

text-overflow: ellipsis;

border-width: 0 8px 0 14px;

-webkit-border-image: url(images/back_button.png) 0 8 0 14;

}

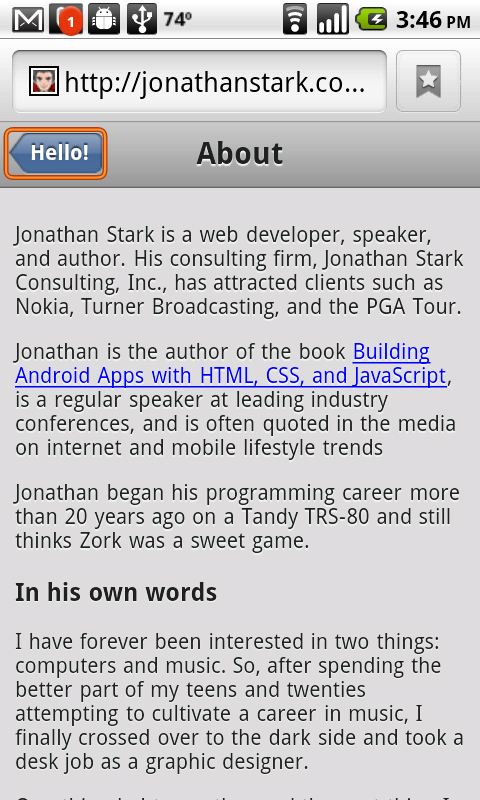

By default, Android displays an orange highlight to clickable objects that have been tapped (Figure 3.7, “By default, Android displays an orange highlight to clickable objects that have been tapped.”). This may appear only briefly, but removing it is easy and makes the app look much better. Fortunately, Android supports a CSS property called -webkit-tap-highlight-color that allows you to suppress this behavior, which I’ve done here by setting the tap highlight to a fully transparent color (see Example 3.12, “Add the following to android.css to remove the default tap highlight effect.”).

Figure 3.7. By default, Android displays an orange highlight to clickable objects that have been tapped.

Example 3.12. Add the following to android.css to remove the default tap highlight effect.

#header div.leftButton {

font-weight: bold;

text-align: center;

line-height: 28px;

color: white;

text-shadow: 0px -1px 1px rgba(0,0,0,0.6);

position: absolute;

top: 7px;

left: 6px;

max-width: 50px;

white-space: nowrap;

overflow: hidden;

text-overflow: ellipsis;

border-width: 0 8px 0 14px;

-webkit-border-image: url(images/back_button.png) 0 8 0 14;

-webkit-tap-highlight-color: rgba(0,0,0,0);

}

In the case of the back button, there could be at least a second or two of delay before the content from the previous page appears. To avoid frustration, I want the button to look clicked the instant it’s tapped. In a desktop browser, this would be a simple process; you’d just add a declaration to your CSS using the :active psuedo class to specify an alternate style for the object that was clicked. I don't know if it’s a bug or a feature, but this approach does not work on Android; the :active style is ignored.

I toyed around with combinations of :active and :hover, which brought me some success with non-Ajax apps. However, with an Ajax app like the one we are using here, the :hover style is sticky (i.e. the button appears to remain “clicked” even after the finger is removed).

Fortunately, the fix is pretty simple. I use jQuery to add the class clicked to the button when the user taps it. I’ve opted to apply a darker version of the button image to the button in the example (see Figure 3.8, “It might be tough to tell in print, but the clicked back button is a bit darker than the default state.” and Example 3.13, “Add the following to android.css to make the back button looked clicked when the user taps it.”). You'll need to make sure you have a button image called back_button_clicked.png in the images subfolder. See the section called “Adding Basic Behavior with jQuery” for tips on finding or creating your own button images.

Figure 3.8. It might be tough to tell in print, but the clicked back button is a bit darker than the default state.

Example 3.13. Add the following to android.css to make the back button looked clicked when the user taps it.

#header div.leftButton.clicked {

-webkit-border-image: url(images/back_button_clicked.png) 0 8 0 14;

}

Note

Since I’m using an image for the clicked style, it would be smart to preload the image. Otherwise, the unclicked button graphic will disappear the first time it’s tapped while the clicked graphic downloads. I’ll cover image preloading in the next chapter.

With the CSS in place, I can now update the portion of the android.js that assigns the click handler to the back button. First, I add a variable, e, to the anonymous function in order to capture the incoming click event. Then, I wrap the event target in a jQuery selector and call jQuery’s addClass() function to assign my clicked CSS class to the button:

$('#header .leftButton').click(function(e){

$(e.target).addClass('clicked');

var thisPage = hist.shift();

var previousPage = hist.shift();

loadPage(lastUrl.url);

});

Note

A special note to any CSS gurus in the crowd: the CSS Sprite technique–popularized by A List Apart–is not an option in this case because it requires setting offsets for the image. Image offsets are not supported by the -webkit-border-image property.

Adding an Icon to the Home Screen

Hopefully, users will want to add an icon for your webapp to their home screens (this is called a "Launcher icon"). They do this by bookmarking your app and adding a bookmark shortcut to their home screen. This is the same process they use to add any bookmark to their home screen. The difference is, we’re going to specify a custom image to display in place of the default bookmark icon.

First, upload a .png image file to your website. In order to maintain a consistant visual weight with other Launcher icons, it's recommended that the file be 56 x 56 if its visible area is basically square, and 60 x 60 otherwise. You'll have to experiment with your specific graphic in order to settle on the perfect dimensions.

Note

Because Android is built to run on many different devices with a variety of screen sizes and pixel densities, creating icons that look good everywhere is fairly involved. For detailed instructions and free downloadable templates, please visit the Icon Design page on the Android developer site (http://developer.android.com/guide/practices/ui_guidelines/icon_design.html#launcherstructure).

Next, add the following line to the head section of the "traffic cop" HTML document, android.html (you’d replace myCustomIcon.png with the absolute or relative path to the image):

<link rel="apple-touch-icon-precomposed" href="myCustomIcon.png" />

Note

As you might have noticed, this is an Apple-specific directive that has been adopted by Android.

What You’ve Learned

In this chapter, you’ve learned how to convert a normal website into a full screen Ajax application, complete with progress indicators, and a native looking back button. In the next chapter, you’ll learn how to make your app come alive by adding native user interface animations. That’s right; here comes the fun stuff!