Section 4.5

APIs, Packages, and Javadoc

As computers and their user interfaces have become easier to use, they have also become more complex for programmers to deal with. You can write programs for a simple console-style user interface using just a few subroutines that write output to the console and read the user's typed replies. A modern graphical user interface, with windows, buttons, scroll bars, menus, text-input boxes, and so on, might make things easier for the user, but it forces the programmer to cope with a hugely expanded array of possibilities. The programmer sees this increased complexity in the form of great numbers of subroutines that are provided for managing the user interface, as well as for other purposes.

4.5.1 Toolboxes

Someone who wants to program for Macintosh computers -- and to produce programs that look and behave the way users expect them to -- must deal with the Macintosh Toolbox, a collection of well over a thousand different subroutines. There are routines for opening and closing windows, for drawing geometric figures and text to windows, for adding buttons to windows, and for responding to mouse clicks on the window. There are other routines for creating menus and for reacting to user selections from menus. Aside from the user interface, there are routines for opening files and reading data from them, for communicating over a network, for sending output to a printer, for handling communication between programs, and in general for doing all the standard things that a computer has to do. Microsoft Windows provides its own set of subroutines for programmers to use, and they are quite a bit different from the subroutines used on the Mac. Linux has several different GUI toolboxes for the programmer to choose from.

The analogy of a "toolbox" is a good one to keep in mind. Every programming project involves a mixture of innovation and reuse of existing tools. A programmer is given a set of tools to work with, starting with the set of basic tools that are built into the language: things like variables, assignment statements, if statements, and loops. To these, the programmer can add existing toolboxes full of routines that have already been written for performing certain tasks. These tools, if they are well-designed, can be used as true black boxes: They can be called to perform their assigned tasks without worrying about the particular steps they go through to accomplish those tasks. The innovative part of programming is to take all these tools and apply them to some particular project or problem (word-processing, keeping track of bank accounts, processing image data from a space probe, Web browsing, computer games, ...). This is called applications programming.

A software toolbox is a kind of black box, and it presents a certain interface to the programmer. This interface is a specification of what routines are in the toolbox, what parameters they use, and what tasks they perform. This information constitutes the API, or Applications Programming Interface, associated with the toolbox. The Macintosh API is a specification of all the routines available in the Macintosh Toolbox. A company that makes some hardware device -- say a card for connecting a computer to a network -- might publish an API for that device consisting of a list of routines that programmers can call in order to communicate with and control the device. Scientists who write a set of routines for doing some kind of complex computation -- such as solving "differential equations", say -- would provide an API to allow others to use those routines without understanding the details of the computations they perform.

The Java programming language is supplemented by a large, standard API. You've seen part of this API already, in the form of mathematical subroutines such as Math.sqrt(), the String data type and its associated routines, and the System.out.print() routines. The standard Java API includes routines for working with graphical user interfaces, for network communication, for reading and writing files, and more. It's tempting to think of these routines as being built into the Java language, but they are technically subroutines that have been written and made available for use in Java programs.

Java is platform-independent. That is, the same program can run on platforms as diverse as Macintosh, Windows, Linux, and others. The same Java API must work on all these platforms. But notice that it is the interface that is platform-independent; the implementation varies from one platform to another. A Java system on a particular computer includes implementations of all the standard API routines. A Java program includes only calls to those routines. When the Java interpreter executes a program and encounters a call to one of the standard routines, it will pull up and execute the implementation of that routine which is appropriate for the particular platform on which it is running. This is a very powerful idea. It means that you only need to learn one API to program for a wide variety of platforms.

4.5.2 Java's Standard Packages

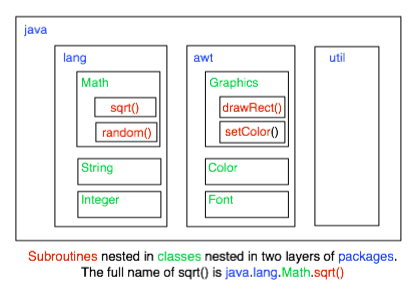

Like all subroutines in Java, the routines in the standard API are grouped into classes. To provide larger-scale organization, classes in Java can be grouped into packages, which were introduced briefly in Subsection 2.6.4. You can have even higher levels of grouping, since packages can also contain other packages. In fact, the entire standard Java API is implemented in several packages. One of these, which is named "java", contains several non-GUI packages as well as the original AWT graphics user interface classes. Another package, "javax", was added in Java version 1.2 and contains the classes used by the Swing graphical user interface and other additions to the API.

A package can contain both classes and other packages. A package that is contained in another package is sometimes called a "sub-package." Both the java package and the javax package contain sub-packages. One of the sub-packages of java, for example, is called "awt". Since awt is contained within java, its full name is actually java.awt. This package contains classes that represent GUI components such as buttons and menus in the AWT, the older of the two Java GUI toolboxes, which is no longer widely used. However, java.awt also contains a number of classes that form the foundation for all GUI programming, such as the Graphics class which provides routines for drawing on the screen, the Color class which represents colors, and the Font class which represents the fonts that are used to display characters on the screen. Since these classes are contained in the package java.awt, their full names are actually java.awt.Graphics, java.awt.Color and java.awt.Font. (I hope that by now you've gotten the hang of how this naming thing works in Java.) Similarly, javax contains a sub-package named javax.swing, which includes such classes as javax.swing.JButton, javax.swing.JMenu, and javax.swing.JFrame. The GUI classes in javax.swing, together with the foundational classes in java.awt are all part of the API that makes it possible to program graphical user interfaces in Java.

The java package includes several other sub-packages, such as java.io, which provides facilities for input/output, java.net, which deals with network communication, and java.util, which provides a variety of "utility" classes. The most basic package is called java.lang. This package contains fundamental classes such as String, Math, Integer, and Double.

It might be helpful to look at a graphical representation of the levels of nesting in the java package, its sub-packages, the classes in those sub-packages, and the subroutines in those classes. This is not a complete picture, since it shows only a very few of the many items in each element:

The official documentation for the standard Java 5.0 API lists 165 different packages, including sub-packages, and it lists 3278 classes in these packages. Many of these are rather obscure or very specialized, but you might want to browse through the documentation to see what is available. As I write this, the documentation for the complete API can be found at

http://java.sun.com/j2se/1.5.0/docs/api/index.html

Even an expert programmer won't be familiar with the entire API, or even a majority of it. In this book, you'll only encounter several dozen classes, and those will be sufficient for writing a wide variety of programs.

4.5.3 Using Classes from Packages

Let's say that you want to use the class java.awt.Color in a program that you are writing. Like any class, java.awt.Color is a type, which means that you can use it declare variables and parameters and to specify the return type of a function. One way to do this is to use the full name of the class as the name of the type. For example, suppose that you want to declare a variable named rectColor of type java.awt.Color. You could say:

java.awt.Color rectColor;

This is just an ordinary variable declaration of the form "type-name variable-name;". Of course, using the full name of every class can get tiresome, so Java makes it possible to avoid using the full names of a class by importing the class. If you put

import java.awt.Color;

at the beginning of a Java source code file, then, in the rest of the file, you can abbreviate the full name java.awt.Color to just the simple name of the class, Color. Note that the import line comes at the start of a file and is not inside any class. Although it is sometimes referred to as as a statement, it is more properly called an import directive since it is not a statement in the usual sense. Using this import directive would allow you to say

Color rectColor;

to declare the variable. Note that the only effect of the import directive is to allow you to use simple class names instead of full "package.class" names; you aren't really importing anything substantial. If you leave out the import directive, you can still access the class -- you just have to use its full name. There is a shortcut for importing all the classes from a given package. You can import all the classes from java.awt by saying

import java.awt.*;

The "*" is a wildcard that matches every class in the package. (However, it does not match sub-packages; you cannot import the entire contents of all the sub-packages of the java packages by saying import java.*.)

Some programmers think that using a wildcard in an import statement is bad style, since it can make a large number of class names available that you are not going to use and might not even know about. They think it is better to explicitly import each individual class that you want to use. In my own programming, I often use wildcards to import all the classes from the most relevant packages, and use individual imports when I am using just one or two classes from a given package.

In fact, any Java program that uses a graphical user interface is likely to use many classes from the java.awt and java.swing packages as well as from another package named java.awt.event, and I usually begin such programs with

import java.awt.*; import java.awt.event.*; import javax.swing.*;

A program that works with networking might include the line as "import java.net.*;", while one that reads or writes files might use "import java.io.*;". (But when you start importing lots of packages in this way, you have to be careful about one thing: It's possible for two classes that are in different packages to have the same name. For example, both the java.awt package and the java.util package contain classes named List. If you import both java.awt.* and java.util.*, the simple name List will be ambiguous. If you try to declare a variable of type List, you will get a compiler error message about an ambiguous class name. The solution is simple: use the full name of the class, either java.awt.List or java.util.List. Another solution, of course, is to use import to import the individual classes you need, instead of importing entire packages.)

Because the package java.lang is so fundamental, all the classes in java.lang are automatically imported into every program. It's as if every program began with the statement "import java.lang.*;". This is why we have been able to use the class name String instead of java.lang.String, and Math.sqrt() instead of java.lang.Math.sqrt(). It would still, however, be perfectly legal to use the longer forms of the names.

Programmers can create new packages. Suppose that you want some classes that you are writing to be in a package named utilities. Then the source code file that defines those classes must begin with the line

package utilities;

This would come even before any import directive in that file. Furthermore, as mentioned in Subsection 2.6.4, the source code file would be placed in a folder with the same name as the package. A class that is in a package automatically has access to other classes in the same package; that is, a class doesn't have to import the package in which it is defined.

In projects that define large numbers of classes, it makes sense to organize those classes into packages. It also makes sense for programmers to create new packages as toolboxes that provide functionality and API's for dealing with areas not covered in the standard Java API. (And in fact such "toolmaking" programmers often have more prestige than the applications programmers who use their tools.)

However, I will not be creating any packages in this textbook. For the purposes of this book, you need to know about packages mainly so that you will be able to import the standard packages. These packages are always available to the programs that you write. You might wonder where the standard classes are actually located. Again, that can depend to some extent on the version of Java that you are using, but in the standard Java 5.0, they are stored in jar files in a subdirectory of the main Java installation directory. A jar (or "Java archive") file is a single file that can contain many classes. Most of the standard classes can be found in a jar file named classes.jar. In fact, Java programs are generally distributed in the form of jar files, instead of as individual class files.

Although we won't be creating packages explicitly, every class is actually part of a package. If a class is not specifically placed in a package, then it is put in something called the default package, which has no name. All the examples that you see in this book are in the default package.

4.5.4 Javadoc

To use an API effectively, you need good documentation for it. The documentation for most Java APIs is prepared using a system called Javadoc. For example, this system is used to prepare the documentation for Java's standard packages. And almost everyone who creates a toolbox in Java publishes Javadoc documentation for it.

Javadoc documentation is prepared from special comments that are placed in the Java source code file. Recall that one type of Java comment begins with /* and ends with */. A Javadoc comment takes the same form, but it begins with /** rather than simply /*. You have already seen comments of this form in some of the examples in this book, such as this subroutine from Section 4.3:

/**

* This subroutine prints a 3N+1 sequence to standard output, using

* startingValue as the initial value of N. It also prints the number

* of terms in the sequence. The value of the parameter, startingValue,

* must be a positive integer.

*/

static void print3NSequence(int startingValue) { ...

Note that the Javadoc comment is placed just before the subroutine that it is commenting on. This rule is always followed. You can have Javadoc comments for subroutines, for member variables, and for classes. The Javadoc comment always immediately precedes the thing it is commenting on.

Like any comment, a Javadoc comment is ignored by the computer when the file is compiled. But there is a tool called javadoc that reads Java source code files, extracts any Javadoc comments that it finds, and creates a set of Web pages containing the comments in a nicely formatted, interlinked form. By default, javadoc will only collect information about public classes, subroutines, and member variables, but it allows the option of creating documentation for non-public things as well. If javadoc doesn't find any Javadoc comment for something, it will construct one, but the comment will contain only basic information such as the name and type of a member variable or the name, return type, and parameter list of a subroutine. This is syntactic information. To add information about semantics and pragmatics, you have to write a Javadoc comment.

As an example, you can look at the documentation Web page for TextIO by following this link: TextIO Javadoc documentation. The documentation page was created by applying the javadoc tool to the source code file, TextIO.java. If you have downloaded the on-line version of this book, the documentation can be found in the TextIO_Javadoc directory.

In a Javadoc comment, the *'s at the start of each line are optional. The javadoc tool will remove them. In addition to normal text, the comment can contain certain special codes. For one thing, the comment can contain HTML mark-up commands. HTML is the language that is used to create web pages, and Javadoc comments are meant to be shown on web pages. The javadoc tool will copy any HTML commands in the comments to the web pages that it creates. You'll learn some basic HTML in Section 6.2, but as an example, you can add <p> to indicate the start of a new paragraph. (Generally, in the absence of HTML commands, blank lines and extra spaces in the comment are ignored.)

In addition to HTML commands, Javadoc comments can include doc tags, which are processed as commands by the javadoc tool. A doc tag has a name that begins with the character @. I will only discuss three tags: @param, @return, and @throws. These tags are used in Javadoc comments for subroutines to provide information about its parameters, its return value, and the exceptions that it might throw. These tags are always placed at the end of the comment, after any description of the subroutine itself. The syntax for using them is:

@param parameter-name description-of-parameter @return description-of-return-value @throws exception-class-name description-of-exception

The descriptions can extend over several lines. The description ends at the next tag or at the end of the comment. You can include a @param tag for every parameter of the subroutine and a @throws for as many types of exception as you want to document. You should have a @return tag only for a non-void subroutine. These tags do not have to be given in any particular order.

Here is an example that doesn't do anything exciting but that does use all three types of doc tag:

/**

* This subroutine computes the area of a rectangle, given its width

* and its height. The length and the width should be positive numbers.

* @param width the length of one side of the rectangle

* @param height the length the second side of the rectangle

* @return the area of the rectangle

* @throws IllegalArgumentException if either the width or the height

* is a negative number.

*/

public static double areaOfRectangle( double length, double width ) {

if ( width < 0 || height < 0 )

throw new IllegalArgumentException("Sides must have positive length.");

double area;

area = width * height;

return area;

}

I will use Javadoc comments for some of my examples. I encourage you to use them in your own code, even if you don't plan to generate Web page documentation of your work, since it's a standard format that other Java programmers will be familiar with.

If you do want to create Web-page documentation, you need to run the javadoc tool. This tool is available as a command in the Java Development Kit that was discussed in Section 2.6. You can use javadoc in a command line interface similarly to the way that the javac and java commands are used. Javadoc can also be applied in the Eclipse integrated development environment that was also discussed in Section 2.6: Just right-click the class or package that you want to document in the Package Explorer, select "Export," and select "Javadoc" in the window that pops up. I won't go into any of the details here; see the documentation.