Consider

![]() , with

, with ![]() . Then we can write

. Then we can write

![]() in polar form as

in polar form as

Forming a geometric sequence based on ![]() yields the sequence

yields the sequence

A natural question to investigate is what frequencies ![]() are

possible. The angular step of the point

are

possible. The angular step of the point ![]() along the unit circle

in the complex plane is

along the unit circle

in the complex plane is

![]() . Since

. Since

![]() , an angular step

, an angular step

![]() is indistinguishable from

the angular step

is indistinguishable from

the angular step

![]() . Therefore, we must restrict the

angular step

. Therefore, we must restrict the

angular step ![]() to a length

to a length ![]() range in order to avoid

ambiguity.

range in order to avoid

ambiguity.

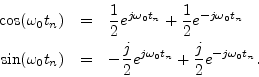

Recall from §4.3.3 that we need support for both positive and negative frequencies since equal magnitudes of each must be summed to produce real sinusoids, as indicated by the identities

The length ![]() range which is symmetric about zero is

range which is symmetric about zero is

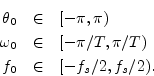

![\begin{eqnarray*}

\omega_0 &\in& \left[-\frac{\pi}{T},\frac{\pi}{T}\right]\\

f_0&\in& \left[-\frac{f_s}{2},\frac{f_s}{2}\right].

\end{eqnarray*}](img1794.png)

However, there is a problem with the point at

![]() : Both

: Both

![]() and

and ![]() correspond to the same point

correspond to the same point ![]() in the

in the

![]() -plane. Technically, this can be viewed as aliasing of the

frequency

-plane. Technically, this can be viewed as aliasing of the

frequency ![]() on top of

on top of ![]() , or vice versa. The practical

impact is that it is not possible in general to reconstruct a sinusoid

from its samples at this frequency. For an obvious example, consider

the sinusoid at half the sampling-rate sampled on its zero-crossings:

, or vice versa. The practical

impact is that it is not possible in general to reconstruct a sinusoid

from its samples at this frequency. For an obvious example, consider

the sinusoid at half the sampling-rate sampled on its zero-crossings:

![]() . We cannot be expected to

reconstruct a nonzero signal from a sequence of zeros! For the signal

. We cannot be expected to

reconstruct a nonzero signal from a sequence of zeros! For the signal

![]() , on the other hand, we sample

the positive and negative peaks, and everything looks fine. In

general, we either do not know the amplitude, or we do not know phase

of a sinusoid sampled at exactly twice its frequency, and if we hit the

zero crossings, we lose it altogether.

, on the other hand, we sample

the positive and negative peaks, and everything looks fine. In

general, we either do not know the amplitude, or we do not know phase

of a sinusoid sampled at exactly twice its frequency, and if we hit the

zero crossings, we lose it altogether.

In view of the foregoing, we may define the valid range of ``digital frequencies'' to be

While one might have expected the open interval

![]() , we are

free to give the point

, we are

free to give the point ![]() either the largest positive or largest

negative representable frequency. Here, we chose the largest negative

frequency since it corresponds to the assignment of numbers in two's

complement arithmetic, which is often used to implement phase

registers in sinusoidal oscillators. Since there is no corresponding

positive-frequency component, samples at

either the largest positive or largest

negative representable frequency. Here, we chose the largest negative

frequency since it corresponds to the assignment of numbers in two's

complement arithmetic, which is often used to implement phase

registers in sinusoidal oscillators. Since there is no corresponding

positive-frequency component, samples at ![]() must be interpreted

as samples of clockwise circular motion around the unit circle at two

points per revolution. Such signals appear as an

alternating sequence of the form

must be interpreted

as samples of clockwise circular motion around the unit circle at two

points per revolution. Such signals appear as an

alternating sequence of the form

![]() , where

, where ![]() can be complex. The amplitude at

can be complex. The amplitude at ![]() is

then defined as

is

then defined as ![]() , and the phase is

, and the phase is ![]() .

.

We have seen that uniformly spaced samples can represent frequencies

![]() only in the range

only in the range

![]() , where

, where ![]() denotes the

sampling rate. Frequencies outside this range yield sampled sinusoids

indistinguishable from frequencies inside the range.

denotes the

sampling rate. Frequencies outside this range yield sampled sinusoids

indistinguishable from frequencies inside the range.

Suppose we henceforth agree to sample at higher than twice the

highest frequency in our continuous-time signal. This is normally

ensured in practice by lowpass-filtering the input signal to remove

all signal energy at ![]() and above. Such a filter is called an

anti-aliasing filter, and it is a standard first stage in an

Analog-to-Digital (A/D) Converter (ADC). Nowadays, ADCs are normally

implemented within a single integrated circuit chip, such as a CODEC

(for ``coder/decoder'') or ``multimedia chip''.

and above. Such a filter is called an

anti-aliasing filter, and it is a standard first stage in an

Analog-to-Digital (A/D) Converter (ADC). Nowadays, ADCs are normally

implemented within a single integrated circuit chip, such as a CODEC

(for ``coder/decoder'') or ``multimedia chip''.